Opinion | Why we aren’t dismissing figuration (and you shouldn’t either)

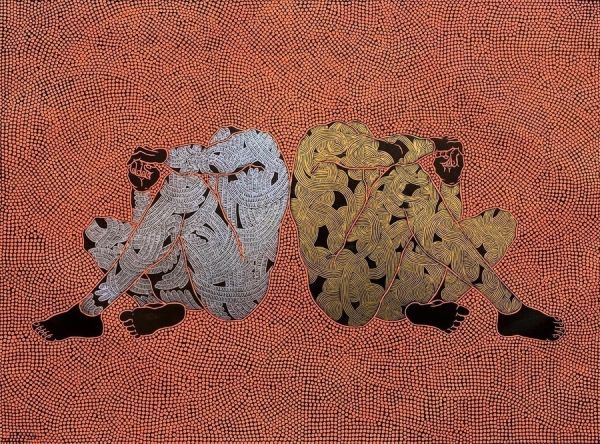

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Destroyer II, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist's website

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Destroyer II, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist's website

---------

2020 was a landmark year for contemporary African art. The pandemic expedited the digitisation of African art and saw many artists turning to social media to create awareness around their work, hoping to stay afloat under extremely challenging circumstances. We saw artists assume the role of creator, marketer and copywriter and the traditional gallery system was called into question.

With people glued to the news and their phone screens with little else to do, it didn’t take long for the brutal murder of George Floyd by police in the US to capture international attention and to spark global outrage. This saw the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and discourse around race and identity yet unmatched in scale; again, as a result of the globalisation that digital tools and platforms enable.

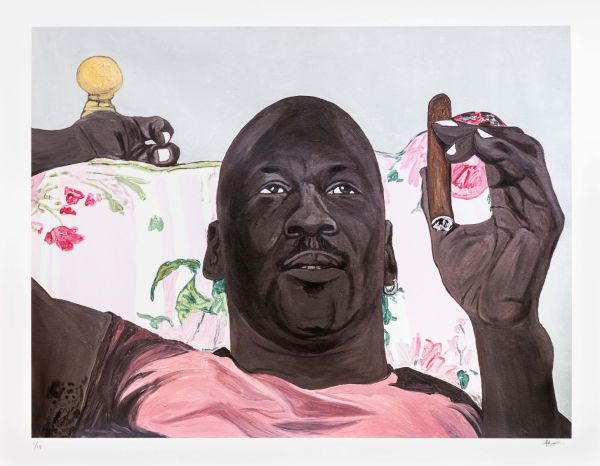

Lerato Nkosi, Consecrated Tyrannies, 2022, R 32,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

Lerato Nkosi, Consecrated Tyrannies, 2022, R 32,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

In the art industry, there was a ‘sudden’ collective realisation that the histories and experiences of Black artists and artists of Color have long been ignored, neglected or actively erased from both public and private collections. Figurative works were highly sought after during this period of time; compounded by the discourse outlined above, we observed an exponential increase in demand for African portraiture, as collectors sought to fill what are often referred to as ‘gaps’ in their collections (Haynes, 2020).

After a three year buying frenzy, we see the demand for Black portraiture declining. While some might argue that this is basic economics and that the demand for and supply of these pieces is simply stabilizing, it is hard to accept this when multiple parties in the local and international industry refer to African portraiture as ‘boring’ or ‘tired.’ So, we ask: what do these shifts in demand indicate about the global art industry and its relationship with contemporary African art? Moreover, what impact do key players in the continental art ecosystem have on this relationship?

Sthenjwa Luthuli, Untold Stories, R 120,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

Sthenjwa Luthuli, Untold Stories, R 120,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

Revisiting the role of technology, it makes sense that there was a significant boost in the demand for and acquisition of Black figurative pieces in 2020; there were not only more collectors looking to acquire the aforementioned, but more contemporary African artists’ works were accessible on digital platforms at this point in time.

However, when the decline in demand for African figuration is reviewed in conjunction with the skyrocketing demand for Latin American artists at present, it highlights that the vast majority of Western collectors and institutions’ acquisitions are trend-driven. This indicates that many still perceive contemporary African art as a trend and that an undercurrent of exoticism, the pursuit of 'otherness', is a key factor in their buying practices.

Zanele Muholi, Bona, Charlottesville, 2015. Image courtesy Berliner Festspiele

Zanele Muholi, Bona, Charlottesville, 2015. Image courtesy Berliner Festspiele

Stepping outside of the realm of portraiture, we observe similar attitudes reflected in Western acquisitions of contemporary African photography. Acclaimed photographers like Ernest Cole, Zanele Muholi and Peter Magubane have never shied away from depicting the harsh social and political realities of South Africa, past and present. While these artists' legacies should not be contended, their work has thrived in international markets, exposed to an audience very far removed from the reality in which it was created.

To transport their audience to a certain time, place and experience is, of course, an artist’s job; however, far too often narratives on the African experience have been reclaimed, reworked and commercialized to the detriment of the work and the artist. We came across a fantastic article by Shantay Robinson wherein she poses a most poignant question: ‘Black people may be present in the western art historical canon now. But are the stories of these regular people being expressed through the work? When we look back, will we know their stories?’

Here, one ought to review the manner in which African galleries, institutions and auction houses market African artists to Western collectors. These key players often position themselves as agents of change; while it would be misguided to argue that they have not advanced the international market for contemporary African art, we question how responsibly they are representing Africa and her artists on a global stage. Are they really seeking to inspire discourse that shifts the narrative around Africa and its art, or are they actively appealing to existing Western ideologies about Africa in pursuit of profits or recognition?

Sphephelo Mnguni, We're Not Poor, 2021, price on request, CONTACT TO BUY

Sphephelo Mnguni, We're Not Poor, 2021, price on request, CONTACT TO BUY

When in a certain setting, many gallerists will admit that ‘poverty porn’ sells; simultaneously, many Black artists are questioning why discussions about their respective oeuvres are largely centered around trauma (Shezi, 2021). While discussing this article with Nkhensani Mkhari (Latitudes Online), he underlined how far removed the realities of many gallerists and influential institutional figures in Africa are from the majority of artists on the ground. Oftentimes, despite presenting work that celebrates Blackness in its various manifestations, the narrative perpetuated by many galleries is centred around the artists’ personal trials or traumas. Many artists have expressed deep frustrations around the commodification of trauma and Micha Serraf addressed this issue quite eloquently when discussing this topic: ‘Of course we have experienced trauma, but it is not the sole lens through which we view life and that, in and of itself, is worth celebrating.’

Instead of pointing fingers at what some are doing wrong, we would prefer to highlight what others are doing right, and it would be remiss of us to omit Zeitz MOCAA from this discussion. Under the directorship of Koyo Kouoh, this museum is successfully communicating that there should not be one broad brushstroke applied to the African experience or art from the continent. From the well-researched and beautifully curated When We See Us to Gilt by Mary Evans, Zeitz is presenting a considered programme that showcases the complexities and nuances of Pan-African identities and experiences.

As we work towards creating a sustainable art market in Africa, we think that it is imperative to reinforce the importance of a multi-faceted contribution to the international industry, one that is isolated from trends. Quite frankly, we think that it is a mistake to dismiss figuration or to refer to it as overdone; after all, how can a three year spotlight on Black portraiture address centuries of neglect and erasure?

- Camilla van Hoogstraten and Zak Buthelezi

References:

Haynes, S., 2020. ‘The Archive Means We Are Counted in History.’ Zanele Muholi on Documenting Black, Queer Life in South Africa [online]. Available via: https://time.com/5917436/zanele-muholi/ [Accessed: 25 April 2023]

Robinson, S., 2022. Why Is Black Portraiture So Popular Today? [online]. Available via: https://www.blackartinamerica.com/blogs/news/why-is-black-portraiture-so-popular-today [Accessed: 25 April 2023]

Shezi, N., 2021. PORTRAITS OF A PEOPLE [online]. Available via:https://www.wantedonline.co.za/art-design/2021-11-10-portraits-of-a-people/ [Accessed: 25 May 2023]

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory