Of Kinship and Divergence:

A Tswana Reflection on Identity Across Borders and The African Artist’s Right to Self-Invention

- By Diablo Santana

__________________________________________________________

Giancarlo Diablo Santana, Portrait of a Healer, 2024, Enquire.

Giancarlo Diablo Santana, Portrait of a Healer, 2024, Enquire.

There is a strange kind of peace that comes from growing up in Botswana — a peace that whispers more than it speaks. A peace not born of resolution, but of avoidance. Not hard-won, but quietly inherited. A peace that is not always freedom.

It is silence.

It is stillness.

It is the heaviness of air that has learned not to shake.

To be Tswana from Botswana is to be raised in a state of near-ritual submission — to tradition, to authority, to whatever order holds the promise of keeping things calm. We are a people shaped not just by peace, but by subservience, by an almost sacred trust in leadership, no matter how little we understand its movements. We are taught to endure, not to demand. To remain modest, even when our spirits rage with dreams that refuse to fit inside the small rooms of our inherited expectations.

In Botswana, expression often finds no official platform. But it still finds a way.

This is the contradiction I live in. And it’s this contradiction that defines not just me, but multiple generations of Batswana artists, eccentrics, dreamers, and subcultural refugees.

When I cross into South Africa, I am recognized — and misread.

South Africans feel a kinship with me. They’re right to. I feel it too. I am Tswana.

But their Tswana experience is shaped by another trauma, another resistance, another kind of fire. Where they were conditioned by apartheid to fight, to speak out, to mobilize and racialize and politicize every utterance of the self, we were conditioned to stay grateful, to remain quiet, to live with the illusion of neutrality.

My identity as a Motswana from Botswana is politicized differently than it might be across the border. Where South Africa wrestles with the legacy of a black-versus-white struggle — apartheid, settler colonialism, and racial capitalism — our burden is shaped by something less visible, but no less violent: tribalism. In Botswana, it is not uncommon for the

dominant Tswana identity, including my own, to cast a long and oppressive shadow over minority groups like the Basarwa (Bushmen) and the Hambukushu.

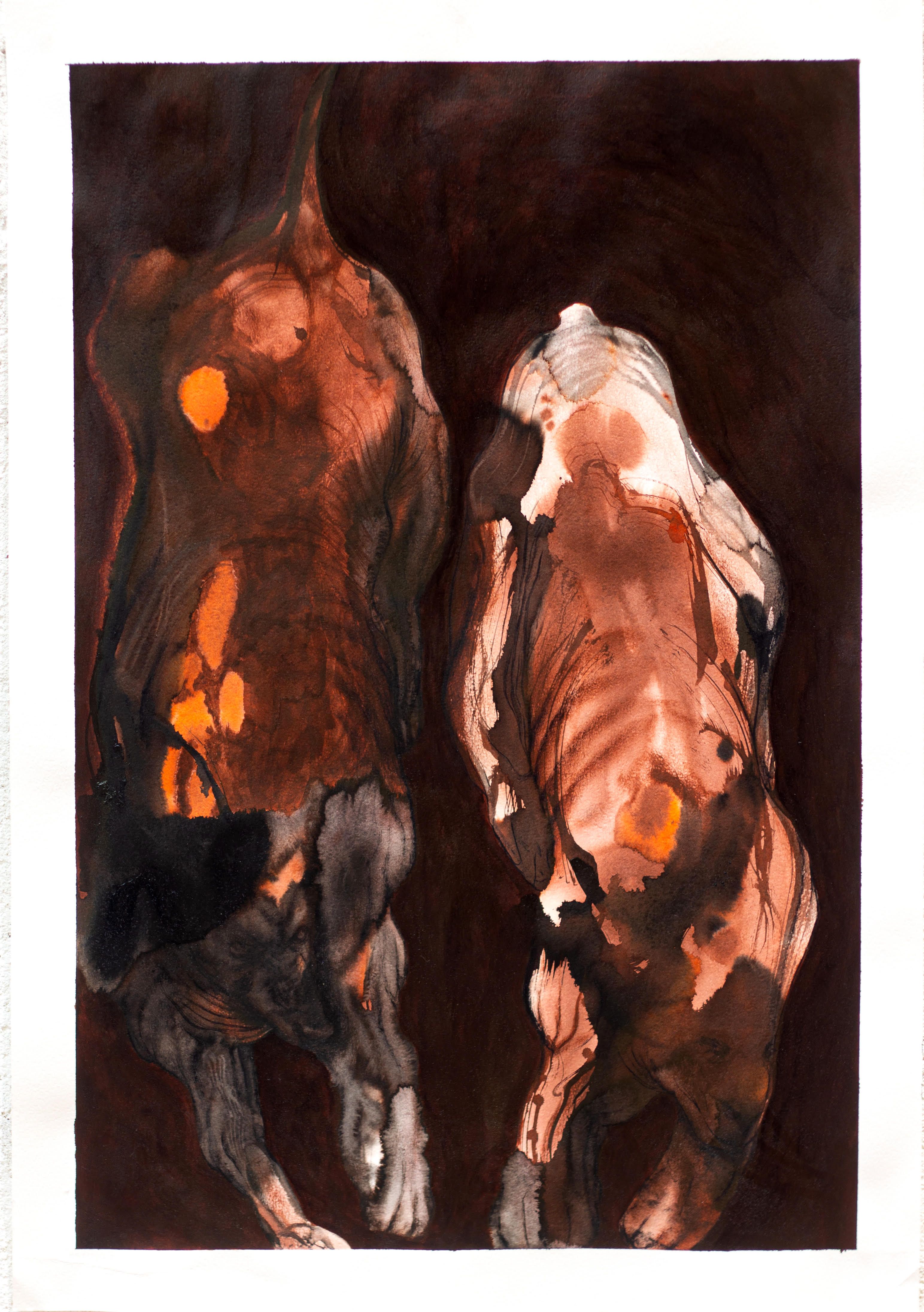

Giancarlo Diablo Santana, Portrait of a Healer II, 2024, Enquire.

Historically, Botswana has been known — quietly, almost shamefully — for the enslavement and exploitation of the various native nomadic groups known as Bushmen or Basarwa in Setswana, particularly as farmhands and domestic labor. This wasn’t some foreign imposition; it was an internal hierarchy, one often perpetuated by Tswana people themselves.

What is most disturbing is that this isn’t merely a relic of the past. To this day, there are parts of the country where Bushmen are still treated as second-class.

Our blood is shared. Our languages are one.

But our emotional worlds? They’ve grown up in different houses.

Thus, we are 100% the same — and 100% not.

And that difference echoes even in something as intimate as a name.

My pseudonym, Diablo Santana, has caused unease — even disapproval — particularly among South African creatives and diasporan artists who feel it doesn't properly "represent" where I come from.

But that discomfort reveals a deeper misunderstanding: that African artists must be documentarians of their nationhood, not authors of their myth.

But that discomfort reveals a deeper misunderstanding: that African artists must be documentarians of their nationhood, not authors of their myth.

I reject that.

I reject the pressure to flatten myself into a single, legible identity — just because I come from Botswana. My name is not an erasure. It is a resurrection.

It is no different from what I see every weekend on football pitches across Botswana.

There, you’ll find men who were never given a shot at professional football. But come Sunday, in their townships and villages, on makeshift fields and bare patches of earth, they are legends. They rename themselves after the greats — not just Ronaldo or Messi or Drogba, but South African giants like Doctor Khumalo, Jomo Sono and Benny McCarthy. This isn’t just mimicry. It’s ritual.

It’s how the working-class Motswana lets himself live inside the dream, even if only for 90 minutes. Even if only through a name.

And this spirit of escapist embodiment is not limited to sport. It lives most vividly in the Maroko subculture — often misread by foreigners as “hellbangers” or “rockers,” but far more profound than those borrowed terms suggest.

Maroko is a homegrown Botswana movement.

A metalhead aesthetic, yes — but more than that, it’s a way of surviving silence through spectacle. Maroko members don’t just dress like rockstars. They become them.

They don leather, spikes, chains, boots — with more intention and drama than any runway show. And once the garments are on, the performance begins.

They might never take to the stage or record a single riff. But that’s not the point.

Each individual is the band. The icon. The myth.

And with that transformation comes a new name. Always a name. A chosen moniker — dark, fantastical, defiant. To the world, they might be anonymous.

To one another, they are legends.

Like me, the Maroko community understands that in Botswana, naming oneself is an act of rebellion, art, and survival all at once.

We do this because the space for formal dreams is nearly non-existent.

There are no institutions to support us and the industries don’t fund us.

So we turn ourselves into icons in the only way we can: through costume, community, and character. Our art is not always on stage or in a gallery — sometimes it lives in the street, the soccer field, the Sunday rally, the backroom gathering, the parking lot pregame.

And in these spaces, the names we choose are not fantasy.

They are freedom.

This is what I wish to tell those who critique my name — and by extension, my right to invent myself. We are not diluting our culture.

We are expanding it.

We are finding ways to be whole in a country that has taught us to stay small.

We are resisting through persona, through play, through the sacred absurdity of alter-egos.

My name, Diablo Santana, is not Western. It is mine.

It is not about erasing Botswana — it’s about allowing Botswana to contain more than just what is expected of it.

Too often, African artists are expected to be pure mirrors of their nations — as if we don’t also live fractured, transnational, hybrid lives. As if we do not dream in soundtracks that were never composed here, but still speak to us more deeply than silence.

As if we do not deserve to build mythologies of our own.

But I do.

And I will.

I am Tswana.

I am from Botswana.

But I do not belong to the small box that category tries to fold me into.

I am not here to perform national pride under someone else’s terms.

I am not interested in being palatable to institutions that do not make room for contradiction. I am not bound to the name my parents gave me – that name is theirs, part of their history. I carry it with honor, but I walk forward with the name I choose – the name that sings the truth of who I am becoming.

My name is my stage. My name is my arena.

It is my right — not to erase where I come from, but to expand what it means to be from here.

Artists outside of the continent are rarely burdened with these questions.

They are allowed to play, to invent, to perform.

But when you're from here, when you're a Motswana artist, you're expected to carry your entire nation on your back, to represent your people with every breath, to never step outside the role assigned to you by birth. And if you do — if you name yourself something else, if you dress differently, if you refuse the script — they say you’re trying to be someone you’re not.

But I am not trying to be someone else.

I am trying to be everything I am — and that includes the dreams I was told were too loud.

My uncle tried to soar away from these same constraints through a single name. He called himself Santana, after his favorite guitarist, and he wrote it into his school documents as though it had always belonged to him. It was bold. It was sacred. It was a small act of resistance dressed as a signature. My grandmother was livid — thought it was foolish, foreign, childish. But I understand now what he was trying to do. He was naming himself into the life he wanted, the music he loved, the freedom he couldn’t otherwise touch.

After his passing, that name — Santana — became heavier, fuller. I took it on not just to honor him, but to finish the story he began. To complete the persona he started writing. To live the version of self-invention that he could only sketch in margins. In taking it, I felt something lock into place. A line drawn from his spirit to mine. A moniker that was always meant to echo beyond one life.

There’s a quiet power in how some African parents name their children after Western icons. It’s not mimicry — it’s belief. The name becomes a kind of blessing, a way of saying, you too can become something great. In that moment, the icon represents the impossible made real — a hope that, despite the weight of environment and the fate it tries to assign, this child might still rise.

It’s the same instinct that led my uncle to call himself Santana. Less about imitation, more about reaching — for freedom, for recognition, for something larger than what the land around us seemed willing to offer.

I love my people. I love where I come from.

But I will not let that love become a prison.

I am not to be defined by national ideals or expectations.

A rockstar defines himself.

This is not performance. This is not rebellion. This is freedom.

I am Diablo Santana.

I am 100% yours — and 100% not.

PAIN CONFIGURATION: SACRIFICIAL GOD / STUDY OF A BULL 3 (2023)

This work was born in mourning — a visual elegy composed after the passing of my uncle. In his honour, I took on his name, completing the pseudonym Diablo Santana — an act of personal mythology, binding grief to legacy. This piece became a portal through which I processed that rupture, not just as personal loss, but as a meditation on sacrifice, ancestry, and the existential costs of being.

At the center of the work is a figure suspended in flux: a cow whose body holds contradictions. The animal begins as a Brahman bull — its neck broad, its forehead noble — and tapers into the form of a pregnant cow. It is neither and both. Masculine and feminine collapse into one ambiguous vessel. This duality is not biological, but symbolic: the animal as a cipher for human life itself — for the totality of existence, with its contradictions, pains, and passages.

The Brahman bull was chosen deliberately. In Botswana — a land shaped by cattle — this animal is prized for its endurance and resilience. It withstands the climate, resists harsh terrain, and thrives where others falter. It is not only a marvel of adaptation, but a creature of deep cultural significance for Southern African Bantu people — including the Tswana and Jona. It is central in life’s defining ceremonies: offered during marriages to bind families together, and slaughtered at funerals to accompany the dead. In both joy and sorrow, the cow is the medium through which we express communion, continuity, and closure.

In pre-colonial times, the cow held a status far beyond sustenance. It was not an animal to be consumed casually, nor one to be slaughtered for mere appetite. Instead, it was a store of value — a living currency — kept within the corral as a symbol of power, wealth, and life itself. To possess cattle was to possess time, lineage, and legacy. A man’s worth was measured not in coin, but in the quiet power of the herd behind his gate.

In those days, when the village required meat to feast, it was not the cow that was sacrificed. Instead, hunters would be summoned — bowmen, trackers, warriors — tasked with moving silently through bushveld and thorn, seeking antelope, wildebeest, kudu. The cow was not touched. It was preserved, reserved for the sacred: for ritual, for passage, for moments when life and death met face to face. It was the animal of ancestors, the animal of union and farewell — a spiritual vessel, not a common meal.

This historical reverence lingers still, folded deep within the image of the animal in this painting. It is not merely a creature. It is a monument to memory. A witness. A relic of pre-colonial logic, where value was held in life, not just in death.

The title Sacrificial God draws on a Setswana phrase: Modimo o nka e metsi — "the wet-nosed god." In this, the cow becomes divine, not through omnipotence, but through service, through sacrifice. It dies so that others may live, and in death, it unites the spiritual and the earthly.

In the image, the animal hovers between life and death, its body rendered without limbs — a gesture toward its utter helplessness, its absolute submission to fate. The paint bleeds downward in long, unrelenting drips — black, red, and crimson — echoing tears, blood, and rain. These drips are not decoration; they are grief made physical. They speak of anguish, frustration, helplessness, and rage. They weep for what has been lost and scream for what remains. The animal is a body undone, weeping not just for itself, but for what it represents — the violence of being, the inevitability of loss, the dignity in sacrifice.

This is abstraction as lament. A violent, expressive configuration of pain. The image writhes with subliminal form but refuses clean representation — because grief itself cannot be neatly rendered. It distorts. It contorts. It

dissolves boundaries. In this way, Pain Configuration stands as a statement on the autonomy of the Black African painter. It resists being boxed, explained, or domesticated. It is not an illustration. It is a rupture. A wound.

Pain Configuration: Sacrificial God / Study of a Bull 3 is a hymn of submission and survival. A visual rite that echoes ancestral logic — of sacrifice, kinship, reverence, and spirit. It does not seek to explain pain. It marks it. Holds it. Bleeds with it. And in doing so, insists that there is something sacred in carrying what we cannot escape.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory