Nobody Loves a Genius Child: Basquiat and the Anxiety of Autonomy

- By Timothy Gawaya

----------

Figure 2: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Anina Nosei at the Anina Nosei gallery in SoHo. New York, 1982. Photo by Naoki Okamoto.

Figure 2: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Anina Nosei at the Anina Nosei gallery in SoHo. New York, 1982. Photo by Naoki Okamoto.

When considering the great artists of the 20th century, the likes of Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp, generally come to mind. Scholars might perhaps contend that this greatness is based on successful experimentation that furthers the medium, influence and appreciation, novel technical practices and, in the face of a dynamic global market, profitability. One need only have a glance at the white walls of the world’s leading art institutions to grasp the position an artist and their work assume; for it is in museums, galleries and auction houses, as much as studios and universities, that art history is made. The great artists are held with the highest prestige in the social and theoretical imaginary, as well as in the annals of Sotheby’s or The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Indeed, the measure of an artist’s work is heralded by their ability to command a space in museum collections and archives.

There is one artist whose works have remained divisive since they were unleashed onto the international stage in the early 1980s: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Truly, if we are to define greatness along the above lines, then Basquiat exceeds the set boundaries. Basquiat is among America’s best-known artists whose fame and influence persists, as is seen by the continual references to his work in contemporary music, film and fashion. It can be widely suggested that his work is among the most imitated of the latter half of the 20th Century. His paintings exist along the intersections of race, class and art history. They at once offered a romantic view of America – the America of Dizzy Gillespie, Jack Kerouac, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis – as well as a condemnation and indictment of its sordid past. Basquiat’s enduring relevance is only matched by the record-breaking profitability of his works. His paintings, aside from drawing large audiences during exhibitions, command hefty price tags that venture well into the hundreds of millions of dollars, rivalling some of the biggest names in art history: your Picassos, Warhols, Rothkos.

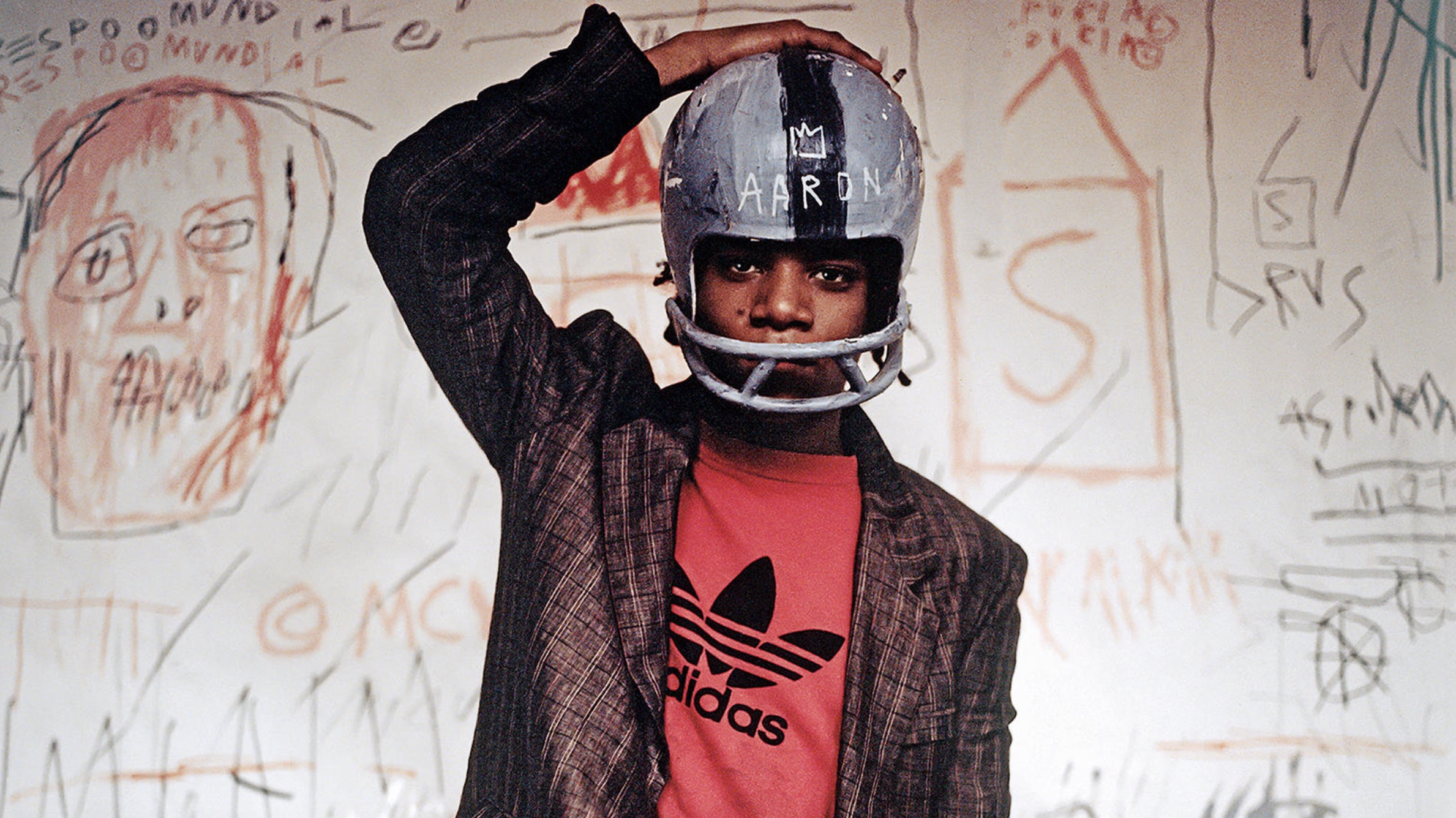

Photo: © Edo Bertoglio, courtesy of Maripol. Artwork: © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Photo: © Edo Bertoglio, courtesy of Maripol. Artwork: © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

However, despite all this, Basquiat’s reputation is steeped in misdirected accusations of primitivism, artlessness and childish naivete by scholars and the general public alike. The disruptive nature of Basquiat’s assault on form, convention, structure, and content has historically elicited dismissals of Basquiat as someone who composes pretty pictures as opposed to an artist in the broadest sense of the term. His work has been characterised as graffiti or street art adapted to the gallery setting, neglecting the technical skill and finesse that conditioned their execution.

As one of the few black fine artists in history to gain such prominence, scholars have historically fallen victim to categorisations of his work that reek of the colonial and its apprehension of alterity. Both Picasso and Basquiat drew influence from African art; the former is a master whose sources span cultures and the latter a primitivist. This speaks to the overall interpretations, analyses and contextualisation of Basquiat’s art: descriptively, his work has been situated in the raw, the visceral, the disorganised. To wit, the ‘urban’. As the quintessential black artist, Basquiat’s works are apprehended as an expression of Afro-America, mainland Africa and the diaspora as a whole – here, from the perspective of a cultural monolith. While neglecting the auto-ethnographic quality of his work as emblematic of particular social, cultural and historical realities, the art market, scholars and perhaps even

the general public, empty the rich textures evident in Basquiat’s canvases in favour of a sterile atomism and juvenile autonomy. It is much easier to sell a revolutionary vision of art to white America if white America doesn’t realise that the revolution is against them.

Untitled 1982 is perhaps one of the more recognisable paintings in recent history, if not among the most expensive. It made headlines in May 2017 when it was sold at Sotheby’s for a jaw-dropping $110.5 million, setting “a new high for a work by a United States artist and is the first work of art created since 1980 that went for more than $100 million” (Kordic, 2021). At a first glance, the viewer is struck by an immediate sense of urgency that labours to make itself known. Critics and scholars have often referred to the raw, edgy, immediacy of Basquiat’s paintings, something Untitled exemplifies brilliantly.

Figure 1: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled 1982, 1982. Acrylic, spray paint, oil stick on canvas. Private Collection

Certainly, the work is striking in its initial assault on the viewer’s visual apparatus.

But to dissuade cauterised readings of Basquiat’s texts and also appreciate them as tapestries animated with very real yet peripheral histories, we must simultaneously take into account Basquiat’s biography and the provenance of the painting.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York on December 22nd 1960 to parents of Haitian and Puerto-Rican descent. His appreciation of art developed as his mother took him to local art museums as a child, with Basquiat citing Picasso’s Guernica as among his favourite works of art. In high school, Basquiat and a friend, Al Diaz, began tagging buildings in Lower Manhattan under the name SAMO (periodically stylised as SAMO©, short for ‘same old shit’). Shortly after, he dropped out of school and left home; subsequently taking on numerous jobs while also selling artworks executed on clothing and other objects as well as continuing his graffiti work at night. The ubiquity of Basquiat’s SAMO work resulted in a degree of fame and notoriety. SAMO was as much a literary experiment as it was an irony-filled polemic against dominant artistic, epistemological, and socio-economic categorisations. As one observer notes, “[more] than simply spray painting his name, SAMO was known for writing pithy critiques of the art world and consumer culture” (Bass, 2015).

Following the dissolution of SAMO in 1980, Basquiat participated in a handful of group exhibitions, notably The Times Square Show and art dealer Anina Nosei’s group show, Public Address. 1982 saw the young artist achieve greater levels of fame, with some scholars contending it to be his most valuable year: “[this] succession of shows in 1982 also served to jumpstart Basquiat’s market; it was the year, Galperin said, “when collectors started to acquire his work en masse.” Nosei was said to be selling his paintings at a breakneck pace” (Gotthardt, 2018). Indeed, 1982 saw the creation of Basquiat’s most expensive and coveted paintings, such as the aforementioned untitled.

Thereafter, Basquiat’s career and reputation continued to grow: a friendship and collaboration with Andy Warhol, sold out shows and exhibitions across the globe, even modelling haute couture. And yet despite his meteoric success, his career was marred with racism, both inside and outside of the art world.

Consider his relationship with Anina Nosei, the art-dealer who granted Basquiat his first professional work space at the basement in her gallery. Controversially, rumours spread of a nasty and disreputable yet wildly talented dreadlocked painter locked in Nosei’s basement. In an interview filmed around the time, Basquiat is quoted as saying: “I was never locked anywhere. If I was a white guy, they would just say artist in residence rather than say all that other stuff” (Chou, 2010). Similar deprecating opinions persist – the unsophisticated, candid nature of his paintings, his lack of technical training, his boorish approach to paint application that made the likes of Pollock appear sacred. Basquiat’s reception into the white-washed milieu of art history was done in such a way as one begrudgingly allows an outsider to share their space while continuously reminding them that they are lucky to even coexist in the first place. Even after Basquiat’s death in 1987 at the age of 27 his work is still used in relation to street art or graffiti – essentially relegated to the unsophisticated, as something that aspires to fine art but fails in its pursuit.

Such misguided readings of Basquiat’s work not only reek of modernist transcendental elitism, but also to the impartial aestheticisation of art history traditionally conceived. As one scholar notes, “the great Eurocentric canon is mediated by a particular relationship to history, through 'forgetfulness' and disavowal” (Coombes, 2001: 244). This undoubtedly raises questions pertaining to what constitutes art, what is worth exhibiting and keeping, and how to redress a supposed disequilibrium in power relations. However, it is not enough to merely frame Basquiat’s position in art history as unequal and exploitative, as much as it is insufficient to posit a “ready formula for analysing power structures that are neither symmetrical nor dichotomous” (Cooper, 2005: 31). Rather, the emphasis should be directed towards utilising these tensions pragmatically – and as such, it is important to note the gradual shift in scholarship towards Basquiat’s work that is suggestive of a deepening appreciation of his artistic merit and integrity.

Certainly, the record breaking nature of Basquiat’s untitled, among others, is representative of a more integrated reading. However, my greatest concern is that this appreciation is inextricably linked to the monetary value, rather than artistic merit, of his paintings – which, in itself, is indicative of a “a world [where] art has become a form of mass entertainment, artistic celebrity and wealth are normal, and art dealers among the most sophisticated economic operators on the planet” (Jones, 2017). Consider the strange way a Sotheby’s executive referred to the successful auction: ““Now he goes into the pantheon of great, great artists,” said Oliver Barker, chairman of Sotheby’s Europe. “It’s as simple as that” (Matthew, 2017). Here the implication is clear enough to not warrant an exhaustive exposition. Such a statement speaks to the underlying hierarchies and categories that more often than not shut out contextual understanding. There is nothing of untitled’s textured meanings, symbolisms, life-story – it has been emptied of its agentive and affective quality as an autoethnographic monograph. When we apprehend it we see dollar signs before a work of art. Having been so far removed from its original historical context – being the vibrant hues and colours of early 80’s New York – the painting now sits in a private collection with its history effaced in favour of an autonomy mediated by the frenzied catatonia of a schizophrenic global economy.

Basquiat: Boom for Real was on show at London's Barbican in 2018, Exhibition photography by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images. Courtesy dezeen Magazine

Basquiat: Boom for Real was on show at London's Barbican in 2018, Exhibition photography by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images. Courtesy dezeen Magazine

And perhaps there has been no greater assault to the artistic legacy of the painting and the artist responsible than the language used by Sotheby’s in their own description: “Basquiat as an undisputed master within the vanguard of young and ambitious image-makers” (Sotheby's, 2017).

In the face of growing interest and popularity, Basquiat’s work introduces the problem of addressing the role of museum collections and archival material in legitimising the emptying of meaning and context that occurs in their spaces. Certainly, these institutions assist in the preservation of artistic tradition and histories. However, the bleeding question pertains to how this preservation occurs, inasmuch as it relates to analysis, description and interpretation. We ask: to what extent is it worth keeping something if the provenance, the history and population, is erased in favour of an autonomy. By this, I mean in considering a particular object solely as a work of art in the peculiar transcendentalism of Kant and Greenberg and not a historical text.

If we are to view an artwork such as Untitled from an atomistic perspective, one that nefariously stresses the autonomy of the art object as a noumenal thing-in-itself, then we neglect the importance that biography, life-story and context have to our experience and interpretation of images and objects. In doing so, we arm ourselves to the teeth and willingly participate in a violent epistemicide.

- Timothy Gawaya is a Pretoria-based researcher and writer

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory