Writing a contemporary South African art history

- by David Mann

---------------

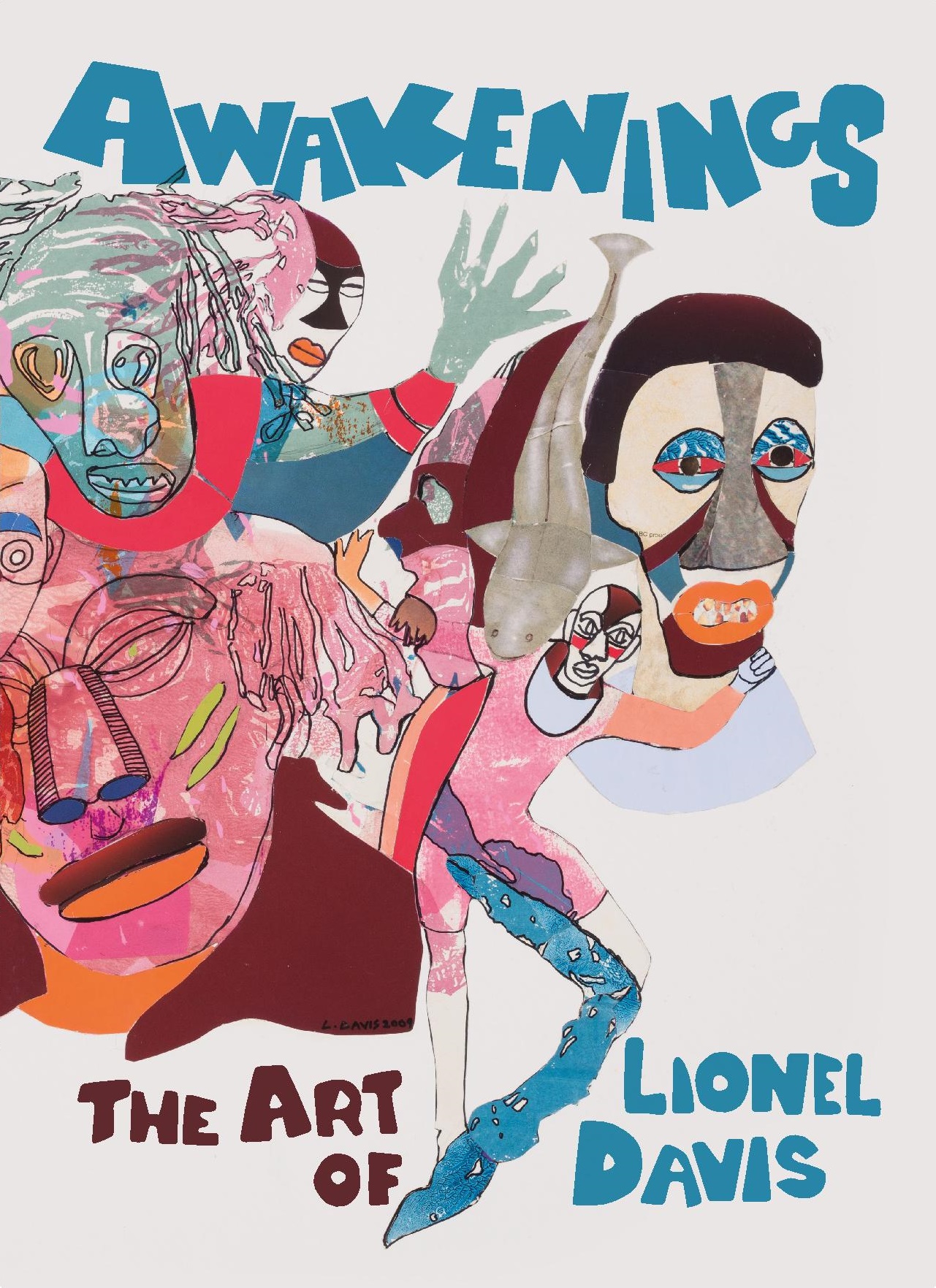

Awakenings front cover, edited by Mario Pissarra, published by ASAI, image courtesy of ASAI

For many, “art history” is a charged term and one that still brings to mind the notion of a rigid, linear timeline of European art movements taught in schools and universities. In South Africa, what function does art history perform? What role has the art historian played in South Africa over the years, and what does the writing of art history look like, today?

Early iterations

In the late 20th century, much of South African art history was still influenced by a Eurocentric model, making sense of art in relation to western ideals. Though attempting to move on from its colonial past, South African art history was largely a revisionist practice, disproportionately carried out by white writers and scholars.

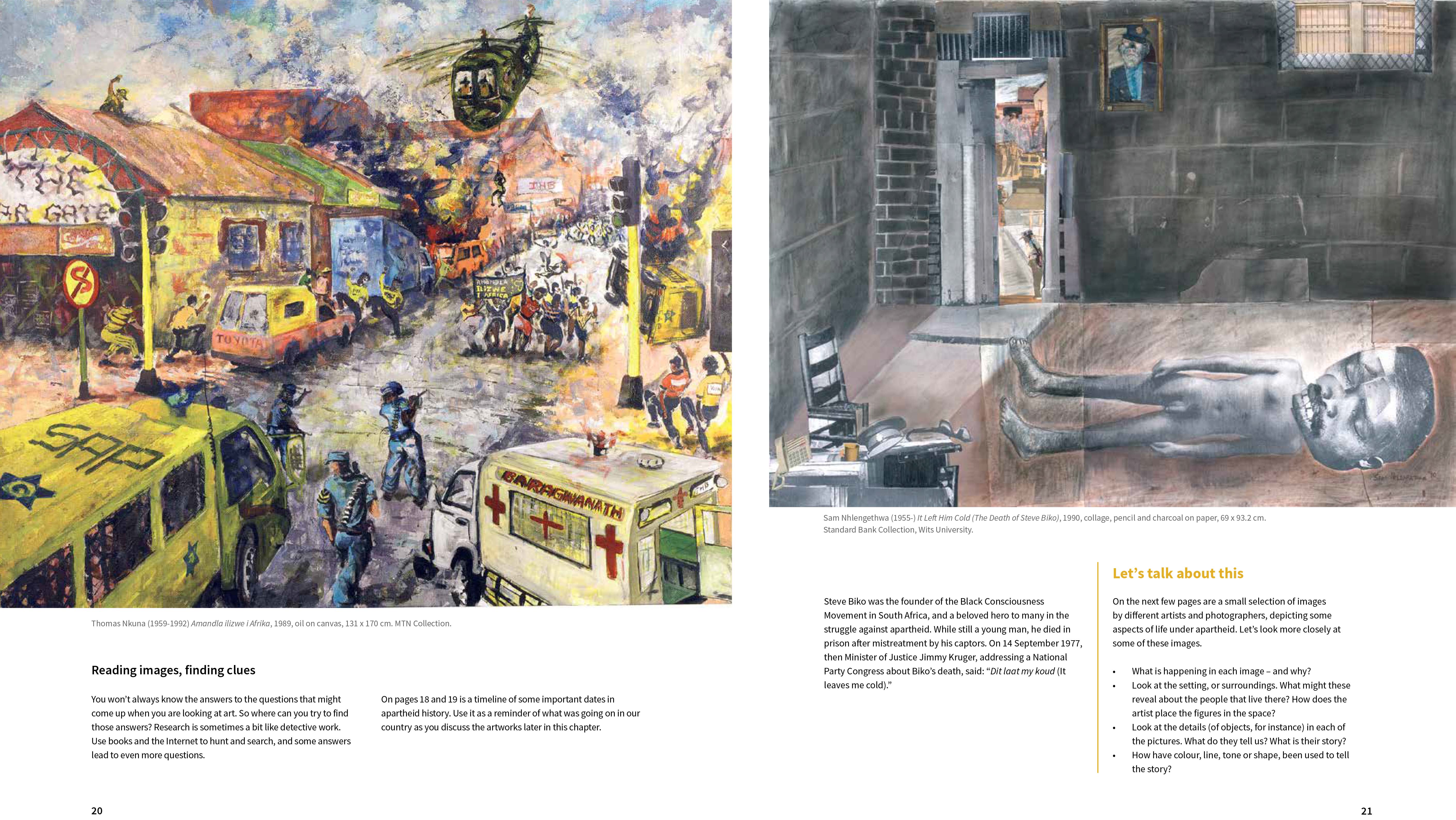

In the 1970s and 80s, Esmé Berman’s Art and Artists of South Africa and Hans Fransen’s Three centuries of South African art set the precedent for publications chronicling the country’s developing art scene. These would later give way to publications like the contentiously titled Resistance Art in South Africa (1989) by Sue Williamson, and Art in South Africa: the future present (1996), co-authored by Williamson and Ashraf Jamal.

When Rain Clouds Gather Exhibition, photography by Lerato Maduna

Outside of publishing, a reframing of South African art history was beginning to take place in schools and independent art spaces, such as The Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA). The artist, teacher, and publisher Elza Miles, recalls how, after being invited by the poet Sydney Sipho Sepamla to join FUBA, they worked to revise and update the Western-focussed syllabus to include Black art and artists from across the country.

“It was difficult to know where to begin. I would spend days at the archives, going through whatever was there and eventually something would jump out,” explains Miles via phone from her home in the Karoo. “These days almost everyone has access to the internet, so it’s become easier in that way, but I also feel that we engage less, now… I suppose I just wanted people to look at the art. It was about being able to access the art in as many ways as possible.”

While these developments in publishing and teaching saw a slight shift from the dominant Eurocentric approach to art history, Black artists were still being written about with little to no comparative context. Their work became exceptional while they remained obscure. Similarly, for every new artist being written into history, countless others were being overlooked.

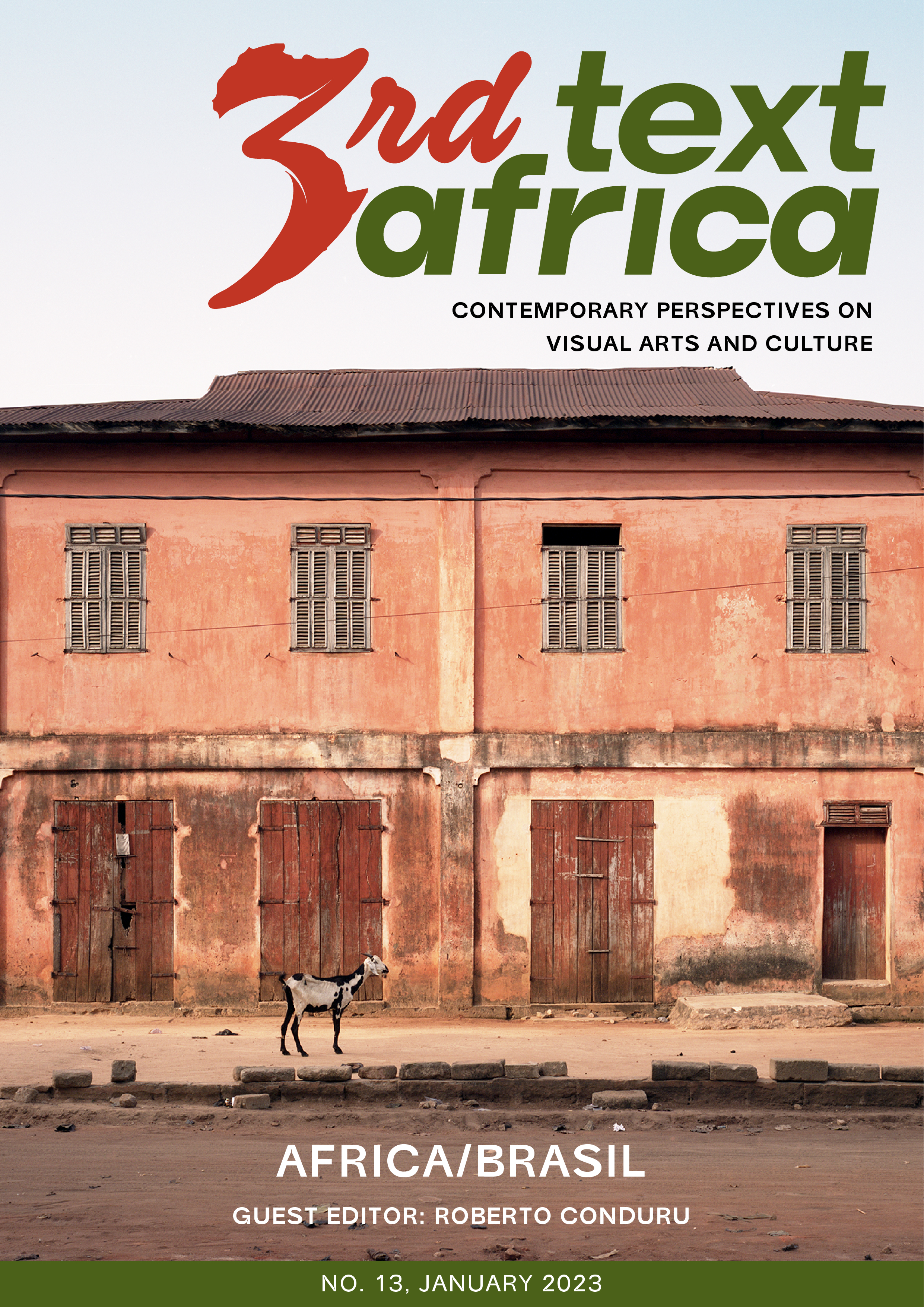

3rd Text Africa No.13. Co-edited by Mario Pissarra. Published by ASAI. Image courtesy of ASAI

Revisiting overlooked artists

Today, much of art history involves revisiting those overlooked artists, weaving them into the greater fabric of the country’s collective artistic history, and locating their practice in a broader African context.

There is a greater number of writers, researchers, and scholars contributing to this history, too. The website and accompanying Instagram account “Art and Theory”, run by Johannesburg-based Claudia Marion Stemberger, is a useful aggregator of the growing amount of writing and research being done across Africa and in the diaspora by artists, academics, critics, curators, and historians.

Journals, publications and monographs continue to house writing on contemporary and historical South African art, and exhibitions such as The Norval Foundation’s When Rainclouds Gather: Black South African Women Artists, 1940 – 2000, Nirox’s Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams, and the Goethe Institut’s Practices of Self-Fashioning, which draws on the Kewpie Collection, are a few recent examples of art institutions and curators activating the art and archives of South African artists.

Amy, Kewpie and Stella at a Go-go Party. Image from the The GALA Queer Archive (GALA)

At a school level, Adventuring into Art, an eight-volume boxed set designed to teach art history and practice to young learners, has been freely distributed to a few schools across the country, and is also available as an online resource for teachers.

Issues of accessibility

The advent of the internet, digital archives, and broader access to information, however, doesn’t necessarily equate to greater access and most traditional archives and resources, whether physical or digital aren’t available to all. As founder and director of the collaborative research and publishing platform Africa South Art Initiative (ASAI), Mario Pissarra puts it: “You have to have means to access them.”

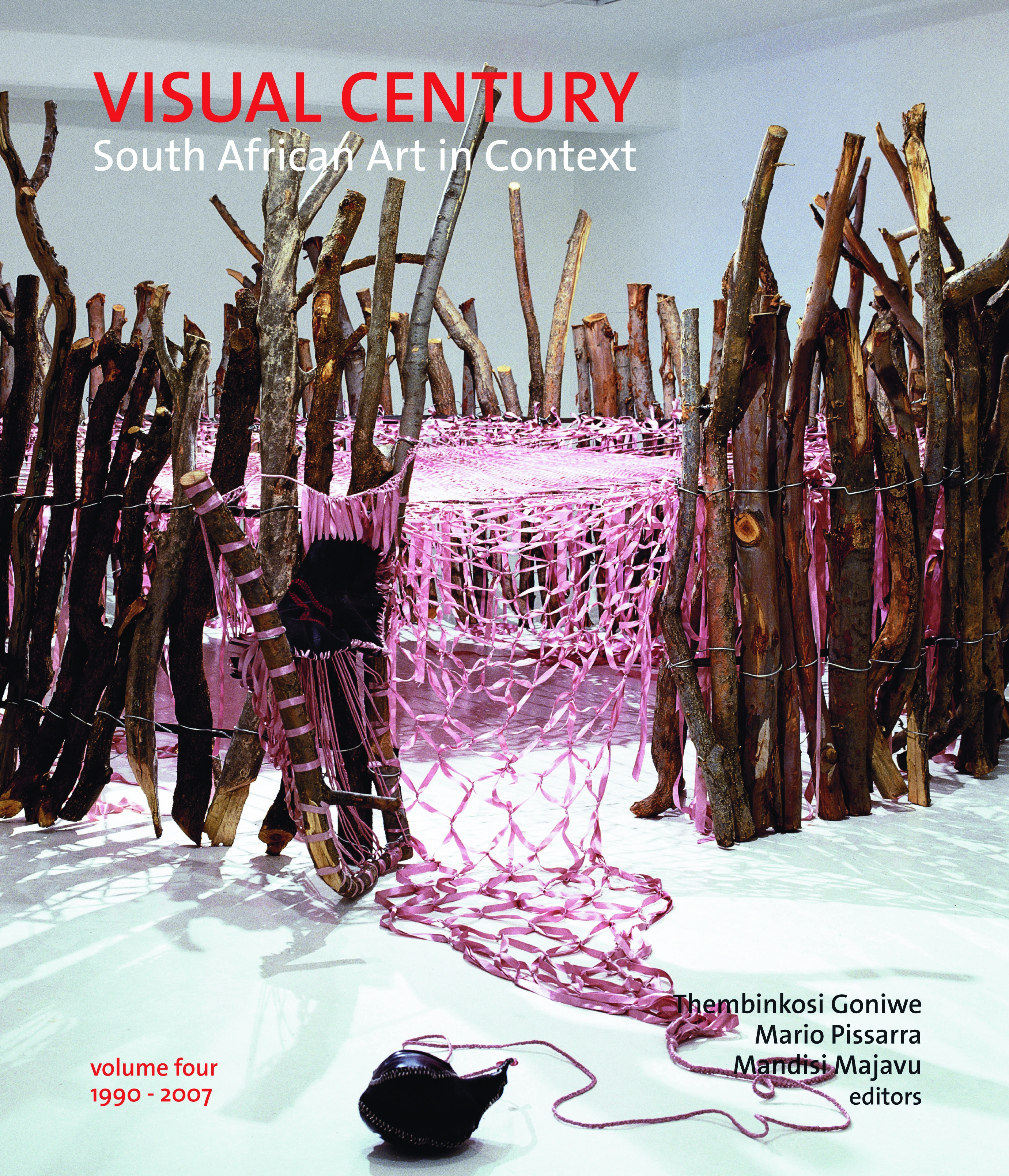

Pissarra is also one of the individuals behind Visual Century, a four-volume survey of one hundred years of South African visual art, on which he worked as editor-in-chief. Published in 2011, Visual Century’s volumes feature a variety authors, as well as editors such as Jillian Carman, Lize van Robbroeck, Thembinkosi Goniwe, Mandisi Majavu, and Pissarra himself.

When Rain Clouds Gather Exhibition Opening, Photography by Natalie Whitehead

It’s been more than a decade since the monumental survey of South African art was published and it remains a vital resource. Reflecting on Visual Century, Pissarra explains via email that access to the publication remains an issue, with calls to have it distributed across schools in South Africa ignored, and publishers remaining reluctant to the idea of making the PDFs freely accessible on ASAI’s website. “This remains a matter of concern as it runs contrary to the spirit of all the work we do – our own print publications are fully accessible on our website.”

The role of the academy

Academic institutions have historically played a vital role in how we come to engage the history of South African art, but also how this history continues to be written, and by who.

For artist, lecturer, and art historian Nomusa Makhubu, the university is an important site for this kind of work, but the discipline of Art History itself still suffers from a stuffy, outdated image, she explains over a video call. Whereas universities in other parts of the world have whole Art History departments with established scholars, South African universities still see the majority of students pursuing practice-based degrees, with Art History occupying a supplementary role at best.

Part of Makhubu’s work to reframe the discipline at a university level has been to eschew the linear breakdown of European movements in favour of a more integrated and contemporary curriculum that engages art history as part and parcel of everyday life. But in viewing art as a means of making sense of the world, there is also the responsibility of bringing the practice of art history into the present.

Imbali Art Book, Six War Zones

“There’s a particular kind of institutional culture that’s cemented by players like art historians. In that sense, we have a responsibility to understand what within that art ecology is marginalised and then be able to work beyond it. Because art historians have, of course, contributed to a somewhat elitist and exclusive understanding of the arts,” says Makhubu. “We have to change the role of the art historian at least in the traditional sense. We’re not just talking in fancy ways about an artwork, we have a broader responsibility to free it from otherwise very exclusive constraints and spaces.”

Engaging archives outside of institutions

In an effort to both encourage scholarship in art history on the continent and address some of these issues around the discipline, Makhubu, along with curator and researcher Amogelang Maledu, founded Creative Knowledge Resources. Since 2018, the interdisciplinary platform has worked to collaborate with art writers and historians through community-centred research. Commissioned texts on underrepresented artists, public lectures and conversations, zines, and curatorial projects are some of the ways in which Makhubu and Maledu go about doing this.

Makhubu also cites the need to increase the scope of what constitutes art history, and to engage different kinds of archives. “We need to seek archives outside of institutions. [This involves] seeking out personal archives, family archives, going outside the scope of institutionalised archives and changing the meaning of what we think an archive is,” she says.

When Rain Clouds Gather Exhibition, photography by Lerato Maduna

For Pissarra, making existing archives more accessible through digitisation, and ushering private archives into the public sphere remain key aims of ASAI: “But it is also important to create new archives, through techniques such as oral history projects and commissioning of texts. People are dying and important records are being lost, and we (the collective ‘we’) are creating a historical record that is founded in good part on erasure (by omission and design) of the complexities of the time.”

Centring the artist, embracing the context

In late 2022, the writer, researcher and academic Pfunzo Sidogi published Mihloti ya Ntsako – Journeys with the Bongi Dhlomo Collection, a book documenting the life, work and art collection of Bongiwe Dhlomo-Mautloa. For Sidogi, contemporary art history needs to adopt an artist-centred approach in its processes and methodologies.

“For too long art historians have concerned themselves with the artefact only, not necessarily at the expense of the artist, but certainly without the artist being the source of the inquiry and interpretation of the work. I am guilty of this approach to writing as well,” says Sidogi. “The problem in South Africa is that this situation tended to be in line with the racialised character of our country, wherein white art historians tended to place a greater value on the work the black artist produced and over the black artist themselves. But ultimately, all art historians regardless of positionality must centre the artist when writing about the art object.”

Visual Century Volume 4. Co-edited by Thembinkosi Goniwe, Mandisi Majavu and Mario Pissarra. Image courtesy of ASAI

There is also the need for sociological perspectives of the ‘success’ of artists, says Pissarra, adding that, in writing on artists and their art, the broader environment in which they work must be taken into account, taking note of the particular trajectory of an artist and what, or who, has contributed to their success and visibility. “There is very little of this kind of research and writing,” says Pissarra. “Instead, we treat artists as individual cases. We gush over their success without looking at how they really got there. And we focus on their themes and iconography, which are relevant, but should not be removed from the broader environment in which they practice.”

Certainly, the history of South African art cannot be told without the history of the country itself. Each artist, moment and movement, is intertwined with the triumphs, tragedies and everyday events of South African life. As a practice, art history continues to evolve and adapt, working to identify alternative methods of researching, archiving, and publishing on the continent and ensuring that there is a record of artists and their work, but also of the world and how we’ve lived in it.

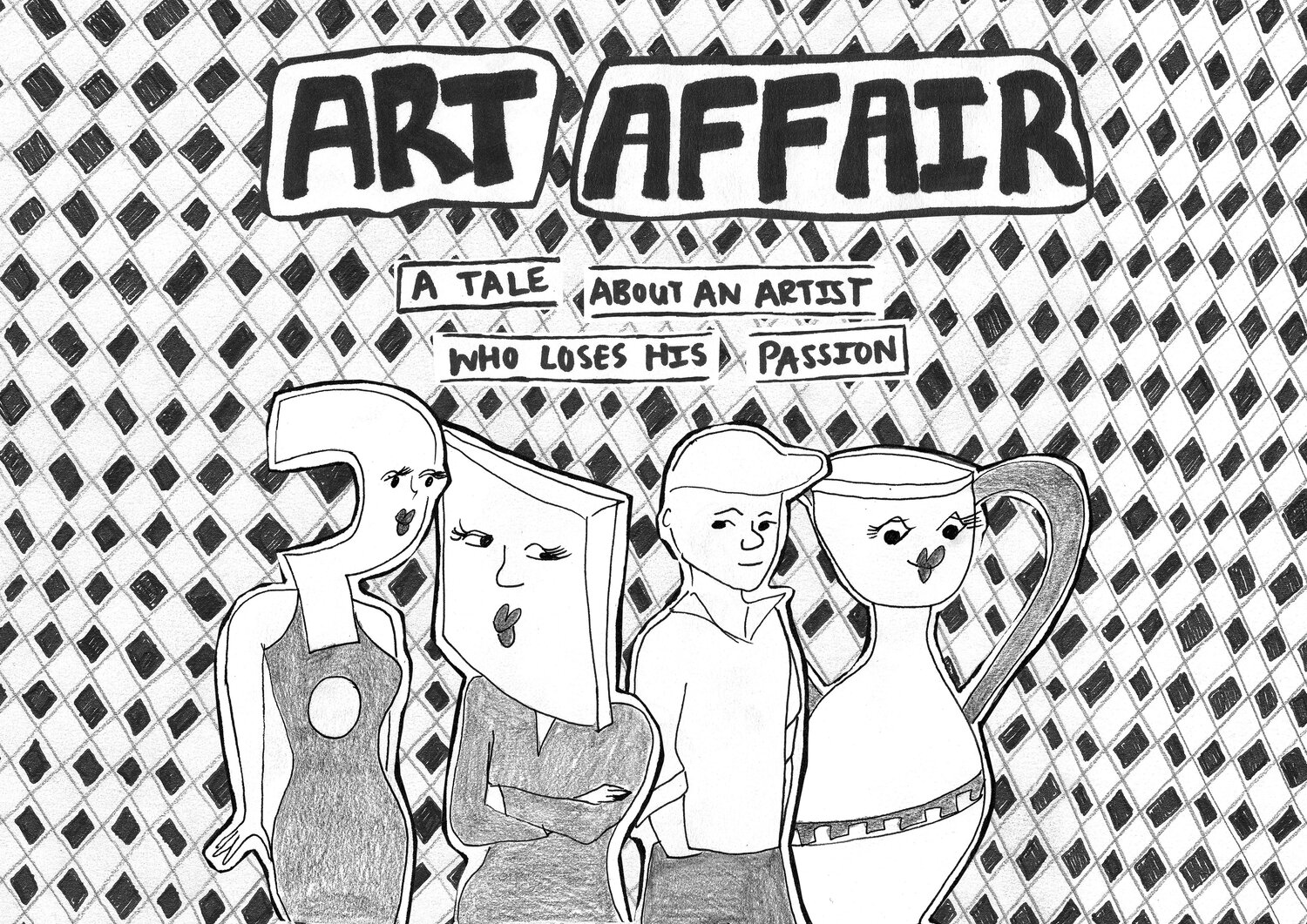

Art Affair Zine on Humour. Bonolo Kavula and Simnikiwe Buhlungu commissioned by Creative Knowledge Resources (CKR). 2021. Images courtesy of CKR.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory