The Ludic Turn: Play, Power, and the Politics of Cultural Transformation in the Global South

- by Nkhensani Mkhari

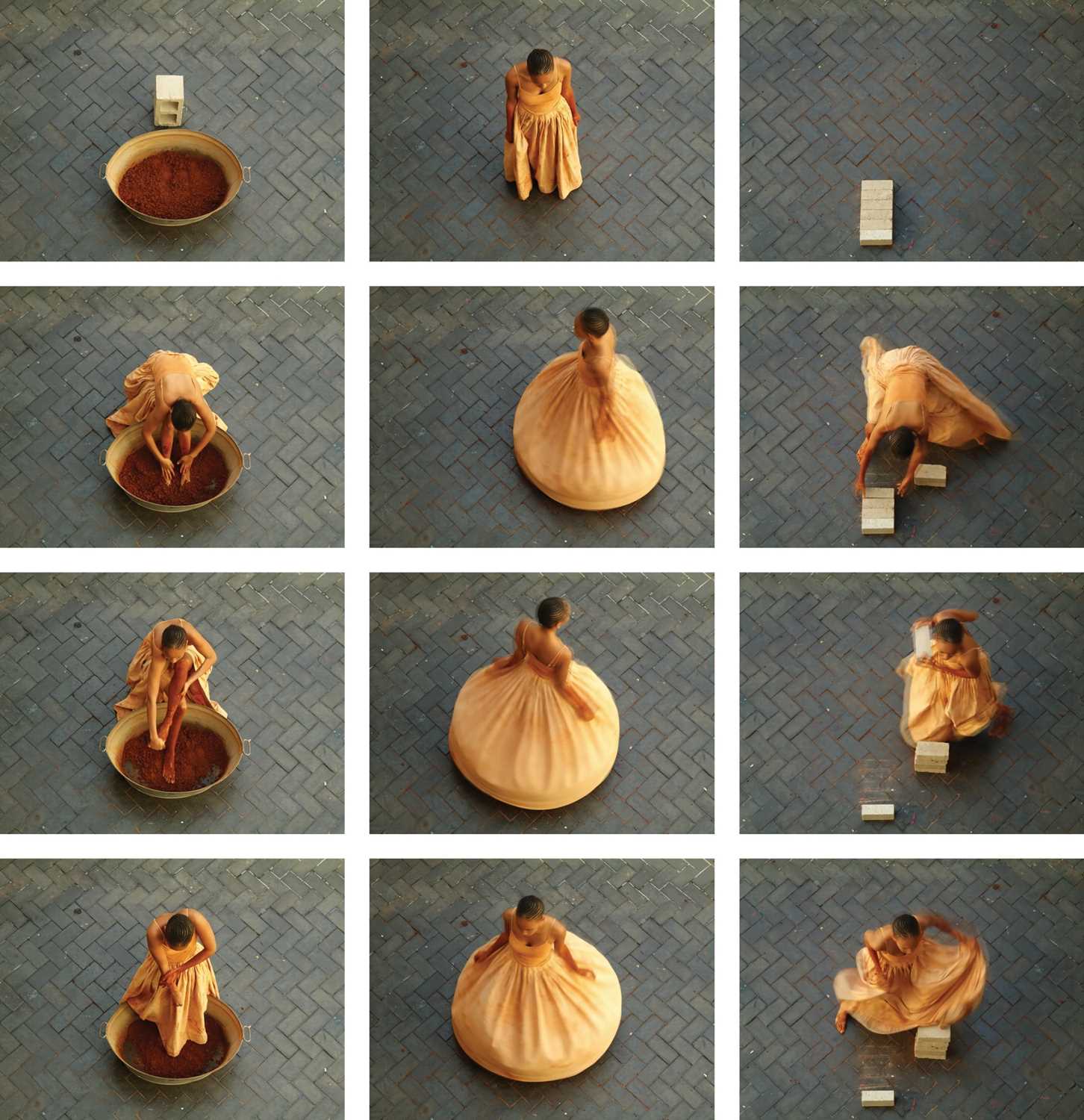

Bronwyn Katz's – Grond Herinnering (2015), Edition of 5. Image courtesy of the artist.

-----------------------------

In recent years, the “ludic turn” has moved from an emerging tendency to a discernible cultural condition. Across the Global South and beyond, curatorial agendas, institutional commissions, and market-facing exhibitions have increasingly foregrounded play, both as a conceptual proposition and as an operative methodology. This is evident in the thematic orientations of major art fairs, the conversion of gallery spaces into interactive environments, and the expansion of scholarly research into participatory and immersive cultural forms. The momentum is undeniable, but the stakes remain contested: is this a genuine embrace of play’s capacity to reconfigure cultural and political realities, or a strategic neutralisation of its critical potential within established economic and institutional circuits?

Emerging in the early 2000s, the “ludic turn” signals a shift towards recognising play as a legitimate mode of knowledge production, cultural expression, and social organisation. While indebted to Johan Huizinga’s foundational arguments in Homo Ludens¹, contemporary interpretations reject his insistence on play’s separation from everyday life. Instead, ludic practice is understood as imbricated with—and capable of intervening in - political, economic, and social realities. In this expanded frame, play is not escapist diversion but a site for critical engagement, community formation, and the rehearsal of alternative futures.

In artistic contexts, this turn is marked by process-driven, participatory, and community-oriented works that privilege collective experimentation over singular authorship and dialogue over monologue. Ludic form operates as a sequence of durational or iterative actions, designed to guide participants through acts of active co-creation, dissolving the traditional distinctions between maker and audience.

In the Global South, play is often mobilised as what Ramón Grosfoguel terms “epistemic disobedience”² - a refusal of colonial epistemologies through the creation of alternative modes of knowing. Here, ludic methodology privileges emergence over resolution, improvisation over prescription, and the collective over the individual.

One compelling manifestation of this is Exhibition Match, an initiative curated by Alexander Richards and Phokeng Setai. Launched in 2023, the project explores the intersection of football and art, reframing the football pitch as a site of cultural play and social choreography. Beyond mere spectacle, it stages questions of collectivism, competition, and the everyday, using the rules and rituals of sport to probe how communities gather, negotiate, and imagine together. Conceived as a social intervention rather than a static exhibition, Exhibition Match has evolved into an annual tournament that convenes artists, curators, and cultural workers on the field. By leveraging the gravitational pull of major art fairs - first in Cape Town and more recently in Johannesburg - it transforms these hyper-commercial nodes into arenas for ludic assembly, opening a space where institutional circuits and informal networks collide under the sign of play.

Exhibition Match

Bronwyn Katz’s Grond Herinnering exemplifies this insurgent potential. Centred on ushumpu, a traditional children’s game demanding intricate cognitive and motor coordination, the work weaves physical gesture - handling soil, spinning, constructing and dismantling brick formations - into a layered oral narrative. Shifting between present reflection and remembered exchanges with her grandmother, Katz stages an intergenerational transmission of knowledge in which play is both method and metaphor. The piece resists the linearity of colonial educational models, foregrounding instead the adaptability, opacity, and communal orientation of indigenous pedagogies.

Such strategies resonate internationally. Ian Cheng’s AI-generated narrative simulations and Stephanie Dinkins’s conversational AI engagements with familial memory demonstrate the global applicability of ludic epistemologies while remaining rooted in culturally specific frameworks.

The ludic turn is driven in large part by younger practitioners who treat play as a form of cultural agency. In doing so, they produce what Joseph Nye describes as “soft power”⁴ - forms of influence operating through attraction rather than coercion - manifested here in the creation of alternative narratives and “hidden transcripts”⁵ that evade formal cultural policy and institutional control.

Play’s speculative capacities link it to Afrofuturist and other world-making traditions, where archival fragments, oral histories, and ancestral cosmologies are recombined to imagine alternative futures. Here, ludic strategies become laboratories for new social imaginaries, enacting possibilities that contest the inevitability of present conditions.

However, as Walter Benjamin warned¹⁰, the radical aesthetics of play risk neutralisation when absorbed into the spectacle economy. The same participatory forms that disrupt hierarchical spectatorship can be repurposed into Instagram-friendly attractions, their political valences softened to suit market and institutional demands. Processual, ephemeral, and community-based works are especially vulnerable to such domestication.

The rhetoric of spontaneity obscures the significant physical, emotional, and intellectual labour underpinning ludic practice. Oupa Sibeko’s ritualistic, participatory performances, for example, assemble temporary communities grounded in affective exchange and embodied knowledge. Yet such work requires sustained resources and support to generate durable transformation beyond the moment of encounter.

To harness the transformative capacity of the ludic turn, practitioners and institutions alike must engage play critically, with sustained attention to power relations and structural conditions. Paulo Freire’s notion of “critical consciousness ¹² offers a guiding principle: playful strategies should be tethered to collective agency, historical awareness, and long-term cultural self-determination.

For the Global South, the ludic turn offers both tools and traps. It can enact refusals of dominant cultural logics and open speculative spaces for imagining otherwise. But to do so, it must resist co-optation, foreground its epistemological insurgency, and remain anchored in the social worlds from which it emerges.

Treasure Mlima, Ukunyathela Ngabantwana, 2023, R60,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY.

The Ludic Turn, as it unfolds here, is not an abstract idea but a lived repertoire enacted across multiple practices. In this exhibition, play appears in dream, in metamorphosis, in street encounter, and in ostentatious display. Treasure Mlima’s carved prints, Ukunyathela Ngabantwana and Held By Dreams, extend play into a cosmological register, where fragments of image and symbol are recombined into worlds neither confrontational nor compliant but insistently African. In Kheonah Nyebe’s New Growth, New Selves, play becomes metamorphosis: a tender, provisional state in which identity, like pastel dust, is smudged, layered, and always in the process of becoming.

Oupa Sibeko pulls the ludic onto the street, dragging canvas across potholes and pavements until the city itself becomes a playfield. His Theme Park reframes leisure and violence alike as marks etched into surfaces, a record of who moves, who rests, and who is excluded. Rebaone Finger turns the ludic toward consumption, where “cheesiness” becomes both parody and utopia. Her ceramic assemblages revel in the slippery tropes of Black luxury - Instagram bouquets, manicured nails, ostentatious display - while insisting on luxuriation as self-care, as self-love, as the refusal of suffrage as the only frame for Blackness.

Oupa Sibeko, Theme Park, 2025, R70,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY.

Together, these works form a constellation of ludic strategies: revealing, transforming, tracing, and luxuriating. They remind us that play is not diversion but a critical method of being otherwise - one that insists on agency, improvisation, and collective imagination. The task, then, is not simply to witness play’s aesthetic force, but to sustain its radical potential against neutralisation, and to follow where its speculative gestures might lead.

References

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955 [1938].

Grosfoguel, Ramón. “The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Political-Economy Paradigms.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 211–223.

Nye, Joseph S. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: PublicAffairs, 2004.

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books, 1968. ¹² Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Continuum, 2000 [1970].

Nkhensani Mkhari animates his ideas in a carefully curated selection of artworks

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory