The Impossibility of Presence:

Oupa Sibeko and Performance as Refusal

- by Nkhensani Mkhari

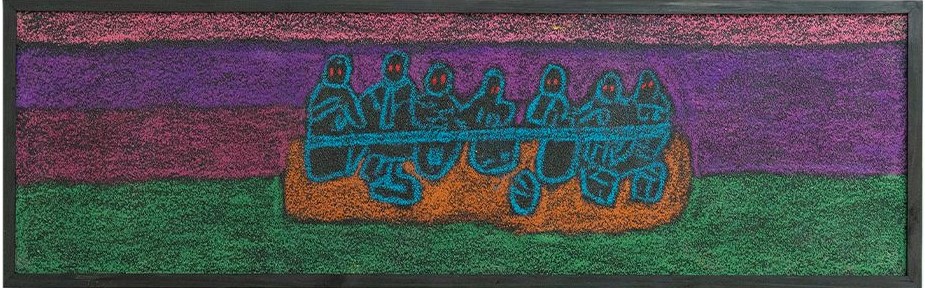

Oupa Sibeko, Sandpaper series VII, 2025, R5,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY.

"The impossibility of Black performance" is not Fred Moten's diagnosis of failure. It is his articulation of a paradox: that Black performance both enacts and refuses visibility, that it appears within the field of representation only to exceed it, that it cannot be fully apprehended or contained within the dominant logics of aesthetics precisely because it is always entangled with capture, spectacle, and commodification. Black performance is impossible not because it doesn't exist, but because it exists otherwise—fugitively, excessively, in the break.

This impossibility finds urgent resonance in the South African context, where the art market's commodity logic collides with performance's fundamental resistance to capture. You cannot hang performance on a wall. You cannot sell it in the same way you sell a painting or sculpture. In a country where commercial galleries dominate the cultural landscape and biennials remain scarce, where alternative modes of exhibition-making struggle for institutional support, performance exists as what we might call a peripheral medium—peripheral not in importance but in its structural refusal of the market's central mechanisms of value extraction and circulation.

Performance in the Deathworld: Necropolitics and the Market

Achille Mbembe, Research Professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, theorizes "necropolitics" as the deployment of social and political power to dictate how some people may live and how some must die, creating what he calls "deathworlds"—"new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead." WikipediaUu But necropolitics operates not only through state violence. It structures the art world itself, determining which cultural forms can circulate, accumulate value, and confer status upon their makers.

In South Africa's highly commercialized art sector, the gallery system privileges object-based practices that can be bought, sold, and displayed—paintings, sculptures, photographs that become assets in private collections. Mbembe argues that the consequences of reducing Africans to objects under colonialism never faded but continue to haunt postcolonial structures. Springer The art market extends this logic of objectification: art itself must become object to enter circuits of capital accumulation. Performance, in its temporal unfolding and spatial specificity, refuses this reduction. It cannot be possessed in the same way. It resists what Mbembe identifies as capitalism's "compulsion to categorize, to separate, to measure, and to name, to classify and to establish equivalences between things."

This is why performance remains peripheral in South Africa despite—or perhaps because of—the vibrancy of its historical tradition. The theatre of resistance under apartheid, the collaborative experiments at the Market Theatre, the township musicals that drew from indigenous performance forms: all existed in complex relation to commodification, often operating outside or against market logics even as they sought audiences and sustainability. In the post-apartheid moment, as the gallery system consolidated and the commercial art market expanded, performance found itself increasingly marginalized within institutional frameworks designed around the circulation of saleable objects.

Forking Knife: Performance as Confrontation

I remember my first encounter with Oupa Sibeko's work at FNB Art Joburg in 2019, before the pandemic reconfigured our relationship to public gathering and physical presence. I was working a booth for the gallery BKhz, immersed in the familiar rhythms of the art fair—the hushed negotiations, the calculated displays, the circulation of collectors and dealers assessing objects for acquisition. Then came the clatter.

In all the humdrum, Sibeko appeared, naked, moving through the walkways on a donkey cart throwing Monopoly money in the air, pulled by his collaborator Benjamin Skinner, his long hair wet dripping on an oversized suit, barefoot, carrying Oupa in a large three-legged cast-iron pot we call a ‘drie-foot’ on the cart. The performance, titled Forking Knife, created immediate disruption. The donkey cart—that vehicle of rural labour and historical dispossession—invaded the sanitized space of the contemporary art fair. The cast-iron pot evoked domestic labour, cooking, sustenance: the realm of the everyday that Njabulo Ndebele called for in his critique of spectacular protest art, yet here deployed not as retreat into ordinariness but as confrontation with the extraordinary violence embedded in ordinary relations.

The performance forced questions the fair's spatial organization sought to suppress: What bodies belong in this space? What forms of labour are visible and valued? How do black and white bodies relate to art—as makers, as subjects, as labour, as spectacle? Sibeko in the pot throwing monopoly money, carried on Skinner back recalled histories of forced labour, of bodies reduced to their capacity to carry, to serve, to produce value for others. The donkey cart moving through aisles of expensive artworks created what Moten might call "the scene of subjection"—making visible the continued operation of colonial logics within contemporary cultural economies.

But Forking Knife was not documentation of oppression for collector consumption. It was refusal. The performance could not be bought by the collectors circulating through the fair. It could not be installed in their homes, added to their portfolios, used to consolidate their cultural capital. It happened and then it was gone, leaving only memory, rumour, the traces carried by those who witnessed it. This is the impossibility Moten describes: Black performance that appears within systems designed to capture it yet exceeds those systems' capacity for containment.

The Peripheral as Strategy: Ritual, Residency, and Institutional Navigation

Sibeko's current position as artist in residence at the University of Johannesburg—part of a two-year programme hosting sixteen artists including Brenton Maart, Mai Al Shazly, and Carol-Ann Davids—demonstrates how performance practitioners navigate South Africa's limited institutional landscape. In the absence of well-funded biennials or sustained support for experimental practice, university residencies become crucial sites for research and development. Yet this reliance on academic institutions rather than dedicated performance venues or curatorial platforms reveals the structural marginalization of the medium.

His recent work at Nirox Sculpture Park, titled "Can a Performance Help Us Remember What the Body Knows?" and hosted by TEDx Johannesburg, positions ritual as climate action. Drawing from African indigenous knowledge systems—particularly around communal performance, theatre in the round, and site-specific work—Sibeko insists on performance as technology of remembrance and ecological care. The body knows what cannot be archived in museum collections or sold through galleries. It carries knowledges that persist through embodied practice, through repetition and variation, through what Diana Taylor calls the "repertoire" rather than the "archive."

This is performance's power and its peripherality: it operates through transmission rather than possession, through presence rather than permanence, through collective experience rather than individual ownership. In a market-driven art world, these characteristics mark it as economically marginal. Yet they also mark it as epistemologically central—as a form that maintains connection to ways of knowing and being that resist commodification.

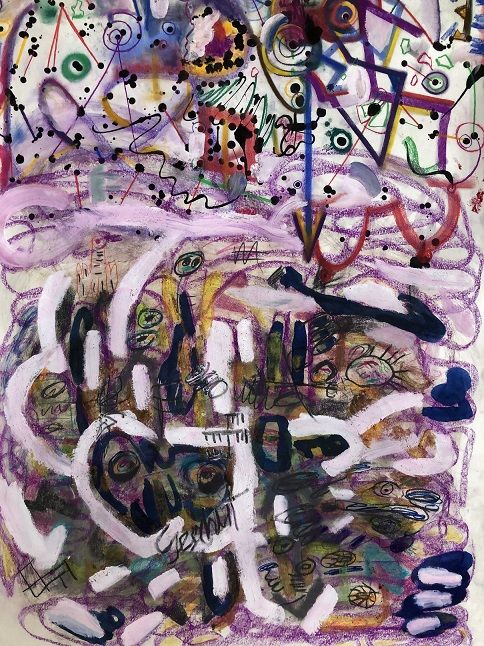

Oupa Sibeko, Sublimate, 2024, R18,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY.

Beyond the Wall: Toward Alternative Frameworks

Njabulo Ndebele argued in "The Rediscovery of the Ordinary" that South African writing had become trapped in spectacular protest, reducing complex realities to legible political statements. He called for literature that could attend to the texture of everyday life, to the subtle operations of power and possibility beyond the dramatic confrontations that dominated anti-apartheid cultural production. Yet the problem was never spectacle itself but rather the ways commodity logics constrain what forms of spectacle become visible and valued.

Sibeko's practice suggests that performance can be both spectacular and subtle, confrontational and careful, impossible to capture yet deeply present. His collaboration with David Krut Projects on Bench Play—creating works on paper through crumpling, tracing spontaneous forms, layering lines and colours—demonstrates how performance practitioners must often produce objects to sustain their practices financially. The works embody what Sibeko identifies as "the rhythms of the workshop space itself: the logo, the shadows, the voices, the air, the simple act of sitting outside with coffee." They translate performance's attention to process and collaboration into forms the market can accommodate.

But this translation is always incomplete, always a compromise. The works on paper cannot fully contain the collaborative methodology that generated them, cannot reproduce the affective dimensions of shared labour and experimentation. They are traces, residues, offerings to a system that demands objects while the performance itself remains elsewhere—fugitive, excessive, impossible.

The Serious Work of Peripheral Practice

Mbembe writes that "war has become the sacrament of our times in a conception of sovereignty that operates by annihilating all those considered enemies of the state." Duke University Press But there are other sacraments, other forms of communion and collective practice that insist on life within deathworlds. Sibeko's performances at art fairs and sculpture parks, his residency work at UJ, his ritual engagements with ecological crisis: all enact what might be called sacramental refusal—ceremonies of presence that acknowledge their own impossibility while happening anyway.

Performance's peripherality in South Africa's commercial art sector is not failure but feature. It marks a practice that exceeds the market's organizing logics, that maintains connection to histories of resistance and communal practice that cannot be reduced to objects for acquisition. In a context where biennials remain scarce and alternative exhibition frameworks struggle for support, performance persists through other means: university residencies, artist-run initiatives, temporary occupations of commercial spaces like art fairs, collaborations with institutions like Nirox that provide platforms outside gallery circuits.

The question is not how to make performance more central—how to render it legible to market logics, how to make it sellable, how to hang it on walls. The question is how to sustain peripheral practices, how to build infrastructure for forms that refuse capture, how to value what cannot be possessed. Sibeko's work reminds us that some things must remain impossible—not absent but present otherwise, not captured but fugitive, not for sale but shared in the break between commodity and gift, between spectacle and ritual, between the market's demand for objects and the body's insistence on knowledge that cannot be contained.

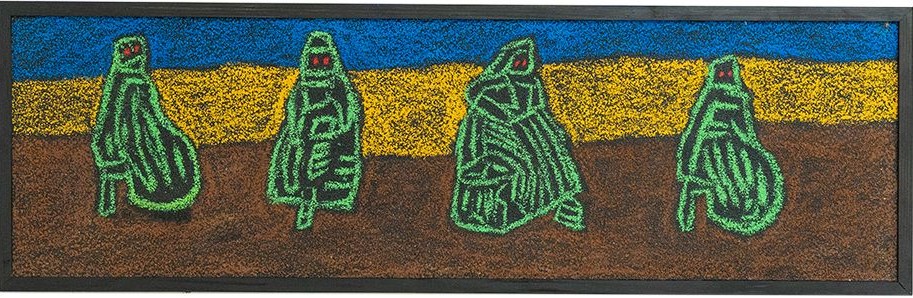

Oupa Sibeko, Sandpaper series IV, 2025, R5,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory