The art of illustration

A generation of artists has been producing works in different mediums that draw inspiration from illustration. Some of the galleries that supported them have closed, but their works remain important and are highly collectible.

--------------------------------

What is the line between illustration and art? This question has had pertinency in South Africa for some time, particularly due to a noticeable increase in works with an illustrative quality featuring heavily in some of the youngest galleries. This has not only been confined to paper drawings as an artist’s main practice, or editioned prints, but also paintings by artists that boast an illustrative quality, such as the landscape paintings by Andrew Sutherland or Shakil Solanki’s oil or ink works depicting male subjects. Some artists draw more heaving from a comic-book language and have harnessed this to make wry commentary on feminist issues.

Coincidentally, the galleries where these kinds of works had been finding traction – Salon 91 and Smith Studio in Cape Town and No End Contemporary in Joburg have all closed their doors. The latter two during Covid-19 and the former more recently. Might this spell the end of illustrative artworks? Many of the artists producing them are graphic designers with commercial careers on the side, the other more prominent artists aligned to the above-mentioned galleries have found their way into other galleries, while the others you have to track down and follow on Instagram if you want to keep up with their work.

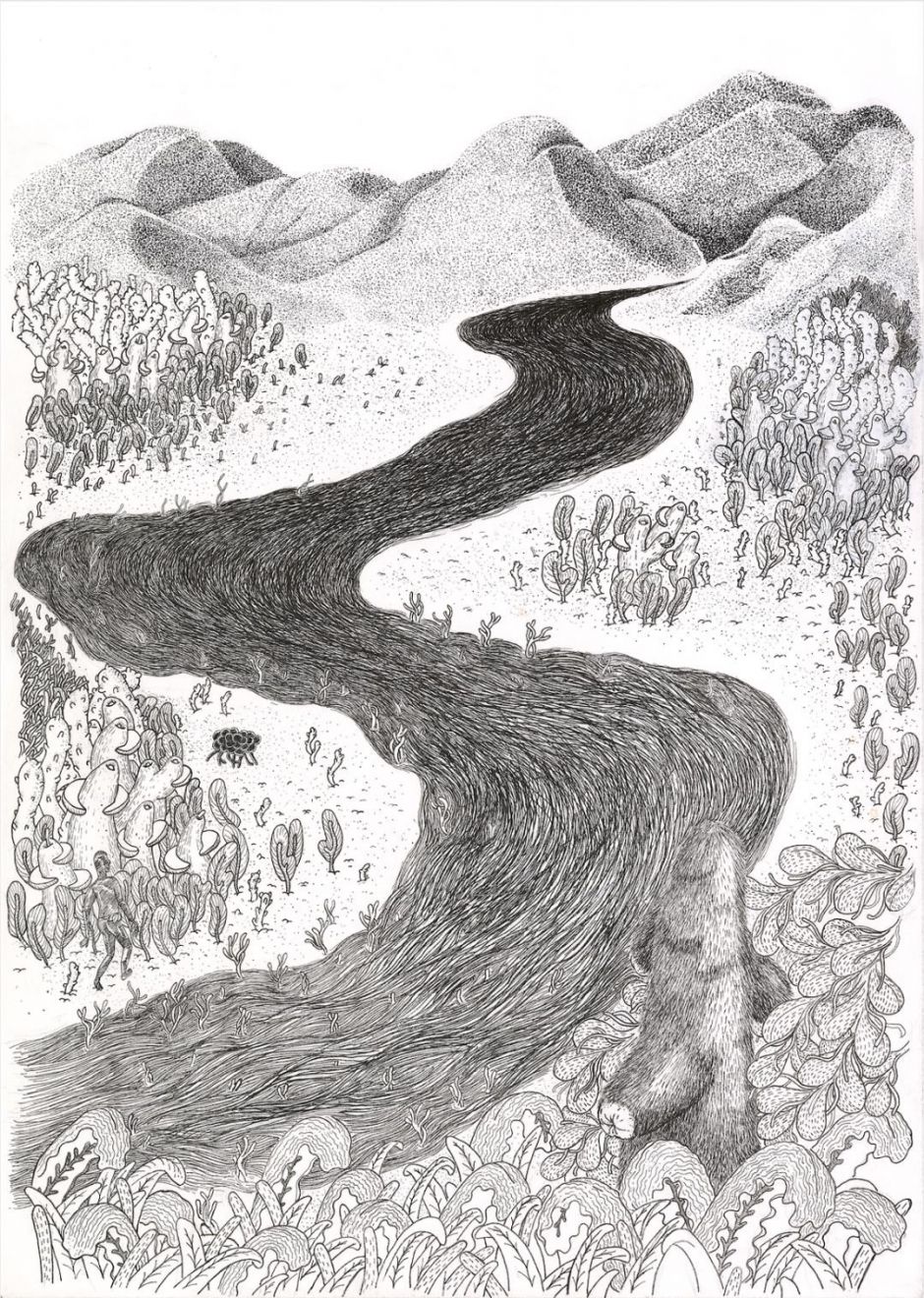

Atang Tshikare, Ea Tshela, 2019, R 12,400.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

This makes these illustrative-inspired artworks even more attractive for collectors; as you have to hunt a little harder for the works you want and you can buy directly from the artists. Undoubtedly, one of the reasons these kinds of works were finding traction in the younger (this would exclude Salon 91 as they existed for over a decade) galleries that serviced a younger group of collectors is not only were they supporting their peers but the works are largely inexpensive and accessible. Illustrative work often lends itself to editioning and editioned prints have are within reach of the young creative class in South Africa who tended to frequent these galleries.

So, what defines an ‘illustrative’ quality?

It may well be subjective, as there are no hard and fast definitions, save perhaps being more decorative, perhaps more detailed, and relating to commercial art forms – such as graphic art, fashion illustration, the publishing industry, advertising, printmaking and comic book art. Of course, these worlds of design have collided with the art world most notably since the 1960s when commercial art and advertising imagery formed the basis for Pop Art.

South African artists have been borrowing from the world of design and advertising for some time. Brett Murray comes to mind with his cartoon-like characters that define his sculptural works to this day but also in his more political paintings where his visual language borrowed from posters and adverts, particularly his imitation of wry slogans in scripto-visual works such as “Promises, Promises, Promises” or “Our Religion must win.”

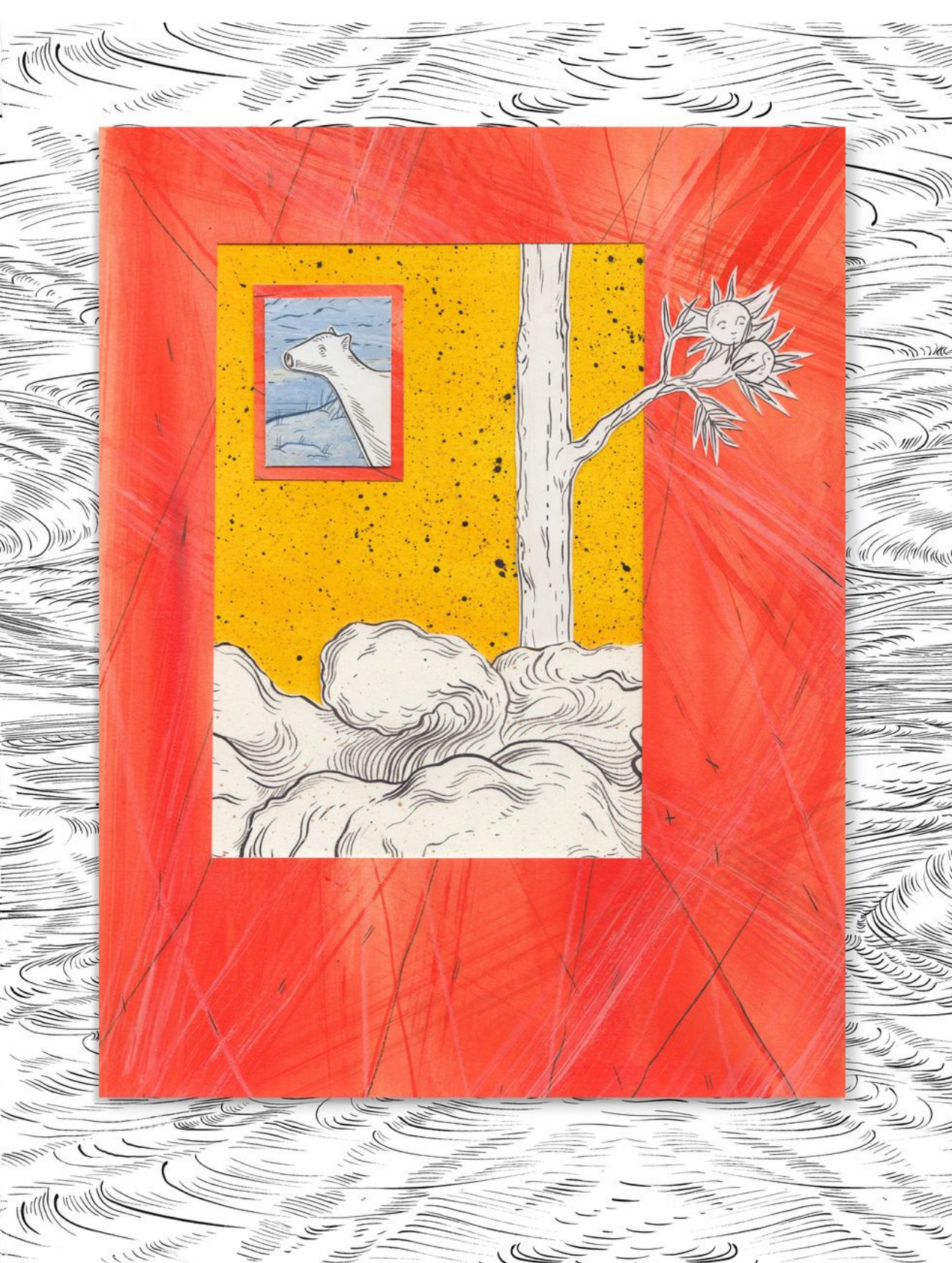

Nina Torr, Just Turn Your Back, 2021, R 4,200.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

Perhaps Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes – the creators of Bitterkomix, the dark, satirical comic books designed to critique and rail against repressive Afrikaner culture - could be more closely credited with smudging the line between art and illustration, particularly as they grew over time into independent artists and the comic book vocabulary traversed into art and their work was made for gallery shows. While their works have come under criticism for being less than ‘woke’ with regards to race and gender, they may well have influenced a younger generation of artists in South Africa to employ a dark illustrative vocabulary.

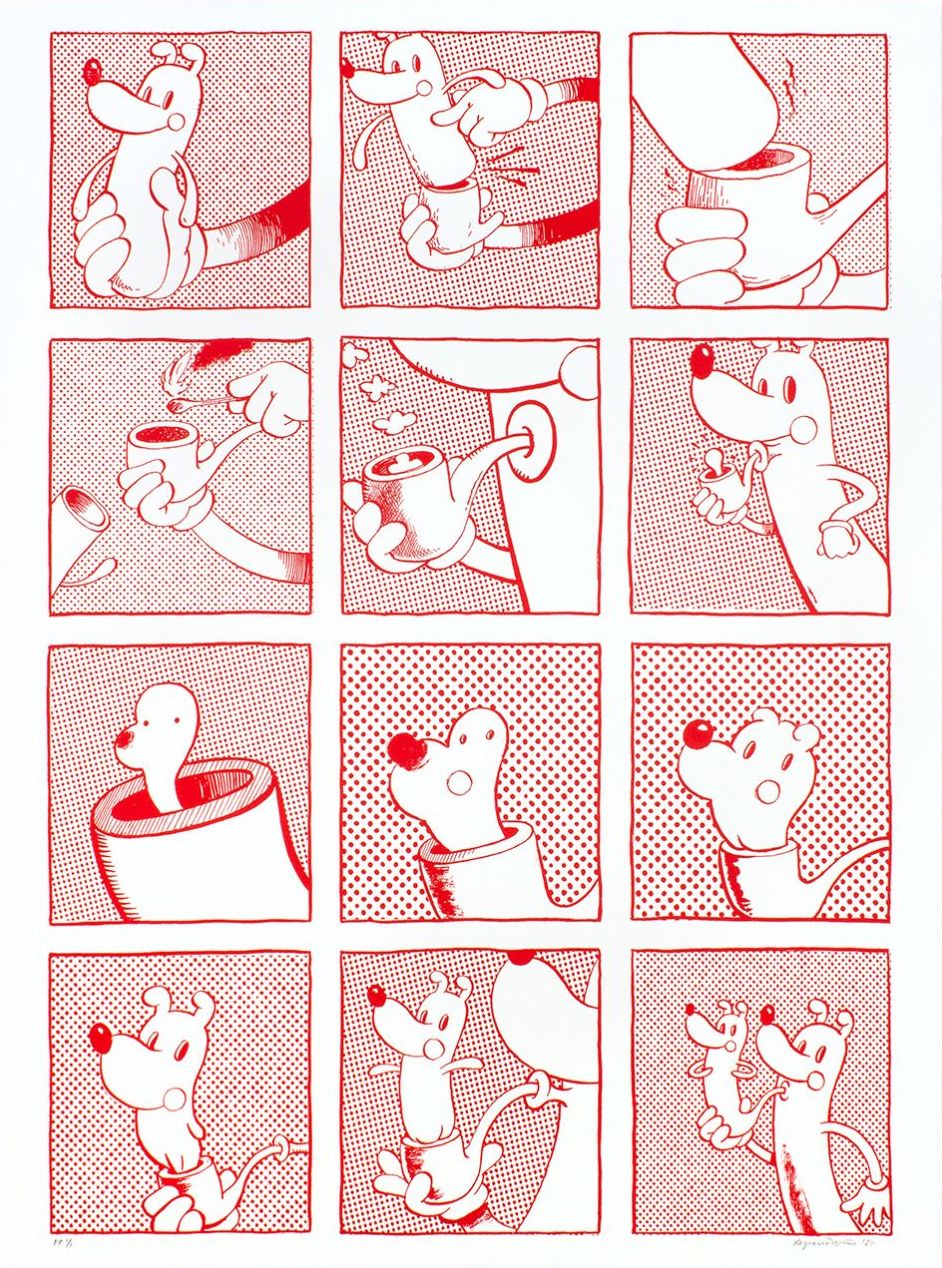

The now-defunct, No End Contemporary gallery in Joburg became home to many young artists making editioned dark satirical paper works or prints that quite literally were grounded in a comic book language – such as Elio Moavero, Shaun Francis, Christi Lee, Dillon Harland and Octavia Roodt. These artists may not have been influenced by Kannemeyer and Botes, perhaps they prepared collectors to more readily be open to art with a comic book twist. The younger set of art buyers that would frequent this Linden-based gallery were more than likely from the world of design and already appreciative of this kind of work.

When you look at the bios of some of these artists they either work as graphic artists or are trained as illustrators. This is also the case for many of the artists that were represented by Cape Town based Salon 91 – from Berry Meyer, Jade Klara, Jean de Wet, Jessica Bosworth Smith, Katrine Classens, Matthew Prins, Nina Torr, Tara Deacon, Sara Pratt and Kirsten Sims.

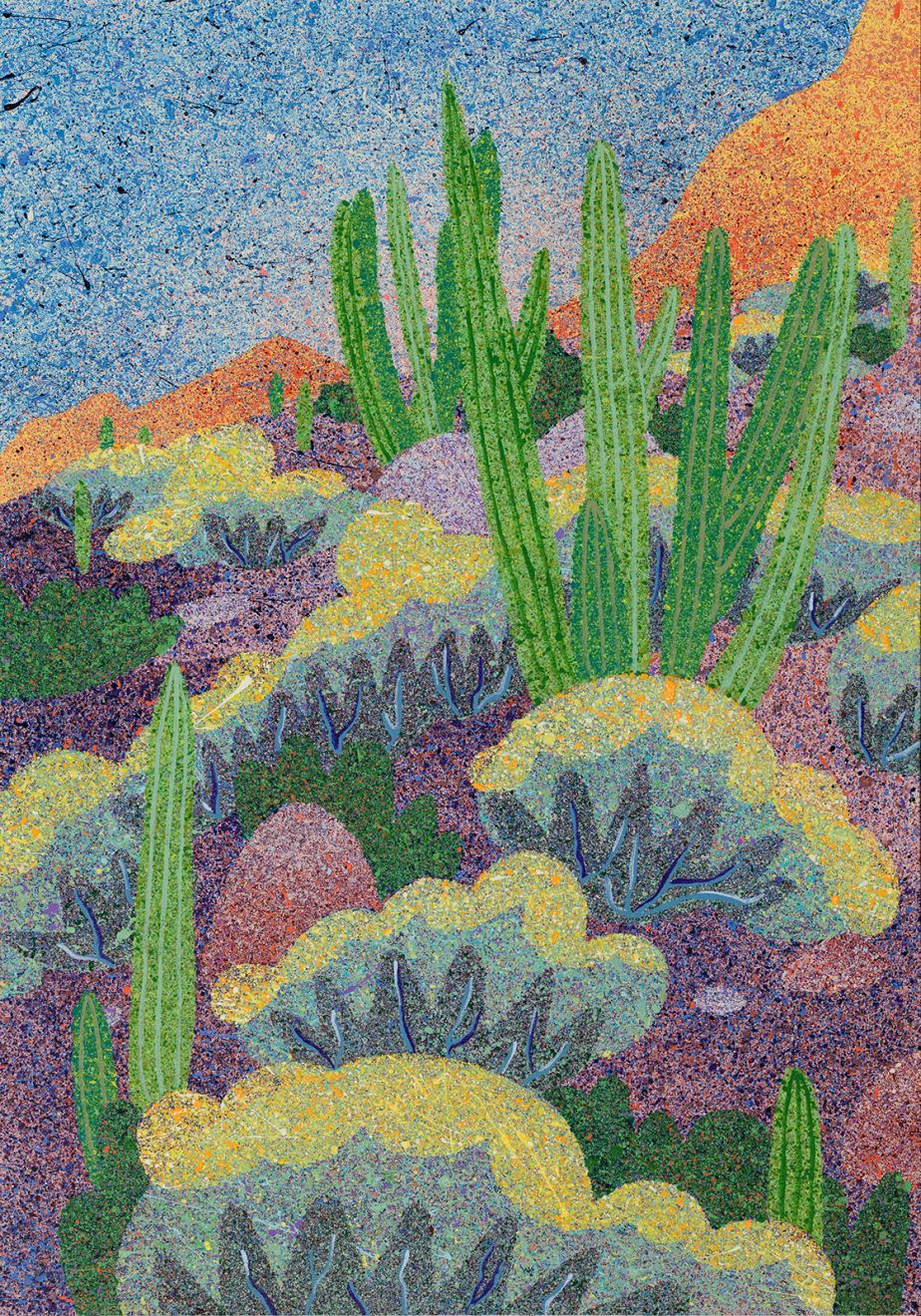

Olivié Keck, Better Me, 2021, R 15,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

As such art made in an illustrative vein, shall we say, has been driven by those with a background in illustration and graphic design. Presumably many spend their working days staring at a screen and drawing with digital tools, so these ink or watercolor paintings, paper or editioned works which are created by hand have provided them with the space to explore a different kind of practice and participate in the art market.

Others come from a traditional art background, such as Solanki.

Solanki’s works, which have popped up at exhibitions all over Cape Town, are defined by a high-detailed, decorative language that brings illustration, fabric design, and classical eastern art to mind.

“I've always been completely fascinated and captivated by Eastern traditional manuscripts and miniatures. The extraordinary details and those very vivid jewel-like colours have always inspired me. There's this inherent richness and grandeur, which feels quite fitting, especially when it comes to tying in queer dynamics and finding a kind of meeting place for those two factors. On a technical level it's what I enjoy most obviously finding an oscillation between the more painterly flowing marks and pieces, but at the same time, there's also more intricate, detailed work,” writes Solanki of his practice.

Some of the artists who were represented by Smith Studio applied an illustrative language to textile works, evoking other kinds of commercial crafts such as Talia Ramkilawan and Michaela Younge. Since that gallery’s closure, they have found their way into more established ones – Whatiftheworld and Smac gallery respectively – most probably since textile works are more highly valued than drawings or editioned prints and they have subverted the narrative or decorative vocabularies they employ.

Ultimately, what makes the works of this generation’s art collectible is that it is rewarding for collectors to fashion a collection where there is a strong stylisic thread and, importantly, that encompasses the expression of a ‘generation’.

Wim Legrand, Pipe dream, 2021, R 3,000.00 ex. VAT, CONTACT TO BUY

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town-based commentator, advisor and independent researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory