K.Skit’s Three Balloons Embraces the Gift of Life Beyond Trauma

The self-taught artist’s multimedia series uses balloons to convey the quest for joy and freedom in the midst of struggle, writes Sandiso Ngubane

With balloons on his head, K.Skit explores how Black people often find healing and joy in spite of the generational and ongoing trauma inherited from historical oppression.

In Paris is Burning, the 1990 film chronicling the New York City ball culture, one of its subjects speaks on being Black and gay in America. ”I remember my dad telling me you have three strikes against you in this world,” he says. “Every Black man has two – being Black and being a man. You are Black, you’re a man and you’re gay. If you’re going to do this, you’re going to have to be stronger than you have ever imagined.”

It’s no different for queer Black men everywhere. Escaping the reality of what you’re up against in the world – specifically racism and homophobia – sometimes means conducting yourself in a way that makes you more ‘palatable’, as artist K.Skits puts it.

The 20-year-old from Alexandra township, north of Johannesburg, recently debuted a body of work titled The Three Balloons under the auspices of Bubblegum Club’s Bubblegum Invites incubator. The initiative was established by the youth culture journal to support emerging artists by providing them with studio space and the resources necessary to bring their work to life.

Born Kgotlelelo Bradley Sekiti, K.Skit’s series explores the “the generational and ongoing traumas of Black bodies; the everyday experiences of queer Black bodies and (the) Black body’s ability to embrace the gift of life through celebration”.

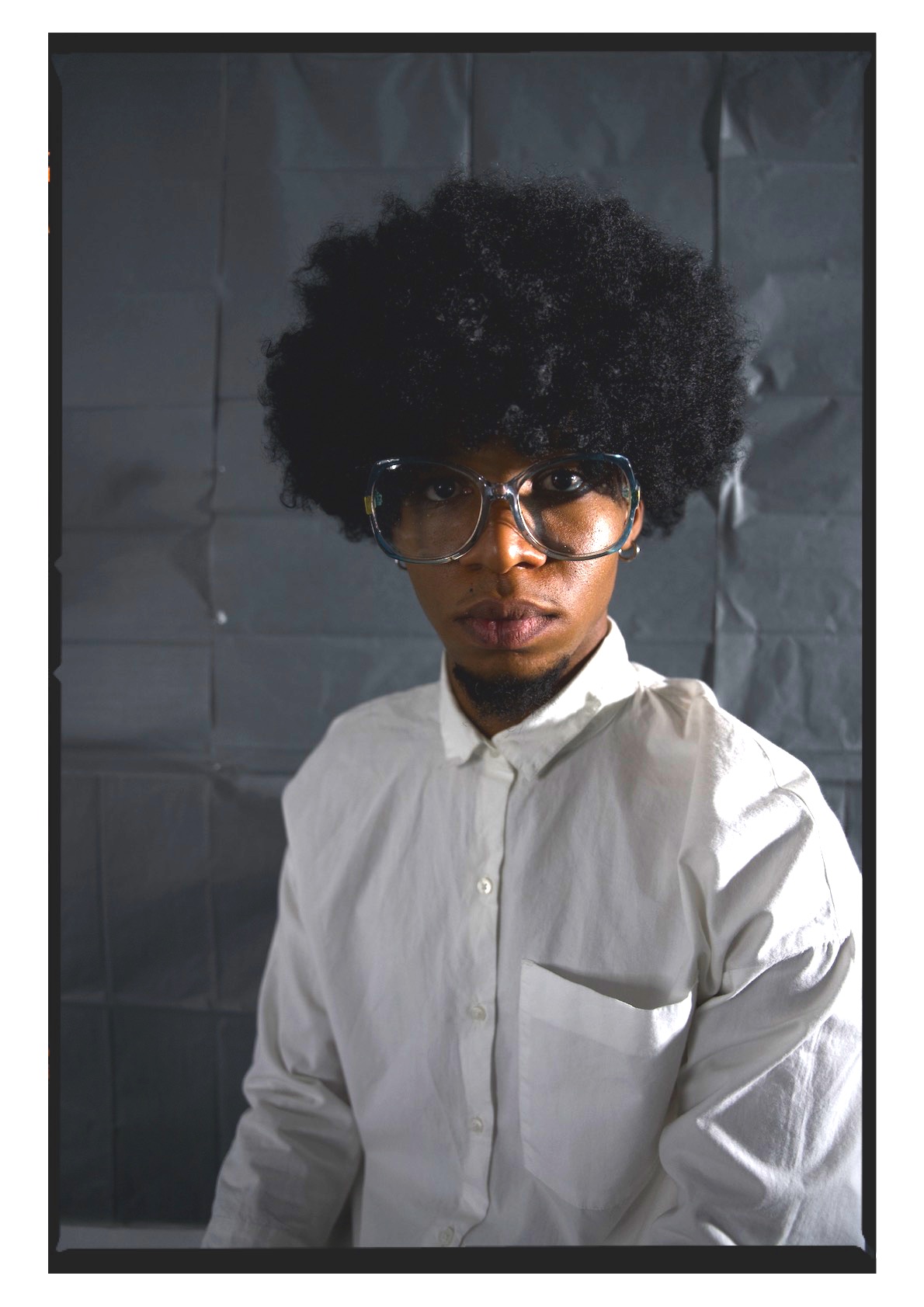

K.Skits wears an afro symbolising blackness and a white shirt as commentary on the sanitisation of blackness he says artists are often cornered into by the palatability requirements of the white gaze.

“My experience as a Black and queer person; there’s a lot of trauma but somehow, even with that trauma we are able to find reasons to celebrate. That’s what the balloons are about,” he explains. “It’s a symbol of celebration. Black people are incredible artists. This is how we find joy and healing. We share that with the world but beyond that, this work is about reclaiming my identity.”

The artist adds that too often Black artists are forced into a space where they have to ‘perform blackness’ for the white gaze.

“What we do has to be palatable. You have to think about how to be Black and acceptable at the same time because we exist in a world that doesn’t like us. For me, this is about being unapologetically Black without having to put on a performance of what that is for someone else.”

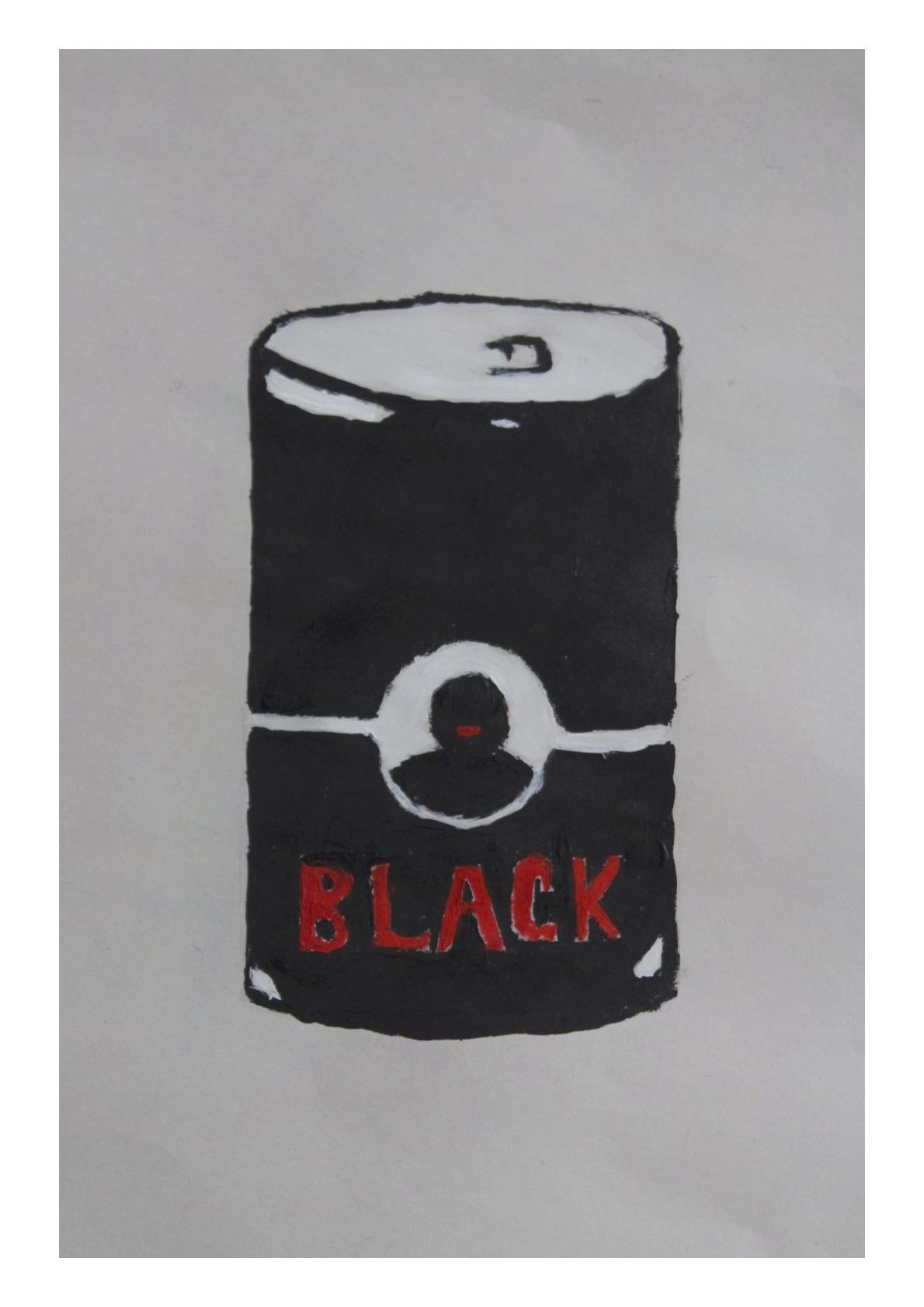

In the accompanying images, some shot on green screen rendered as a red background, K.Skits wears balloons covering his face. In others he wears an afro as a representation of blackness. “There are images where I’m wearing all-white; looking clean. That’s about the palatability we’re forced into but this also interacts with my queer experience so I’m half naked. Often, as queer Black men we are seen as meat. If we’re not being sexualised, we are kept around for clout or we constantly have to educate. In one way or another, we’re being taken from or our culture is being appropriated and exploited. The beans (in the one painting) symbolise the fact that some see blackness as a product you can get off the shelf. You choose how to consume that product whichever way you like.”

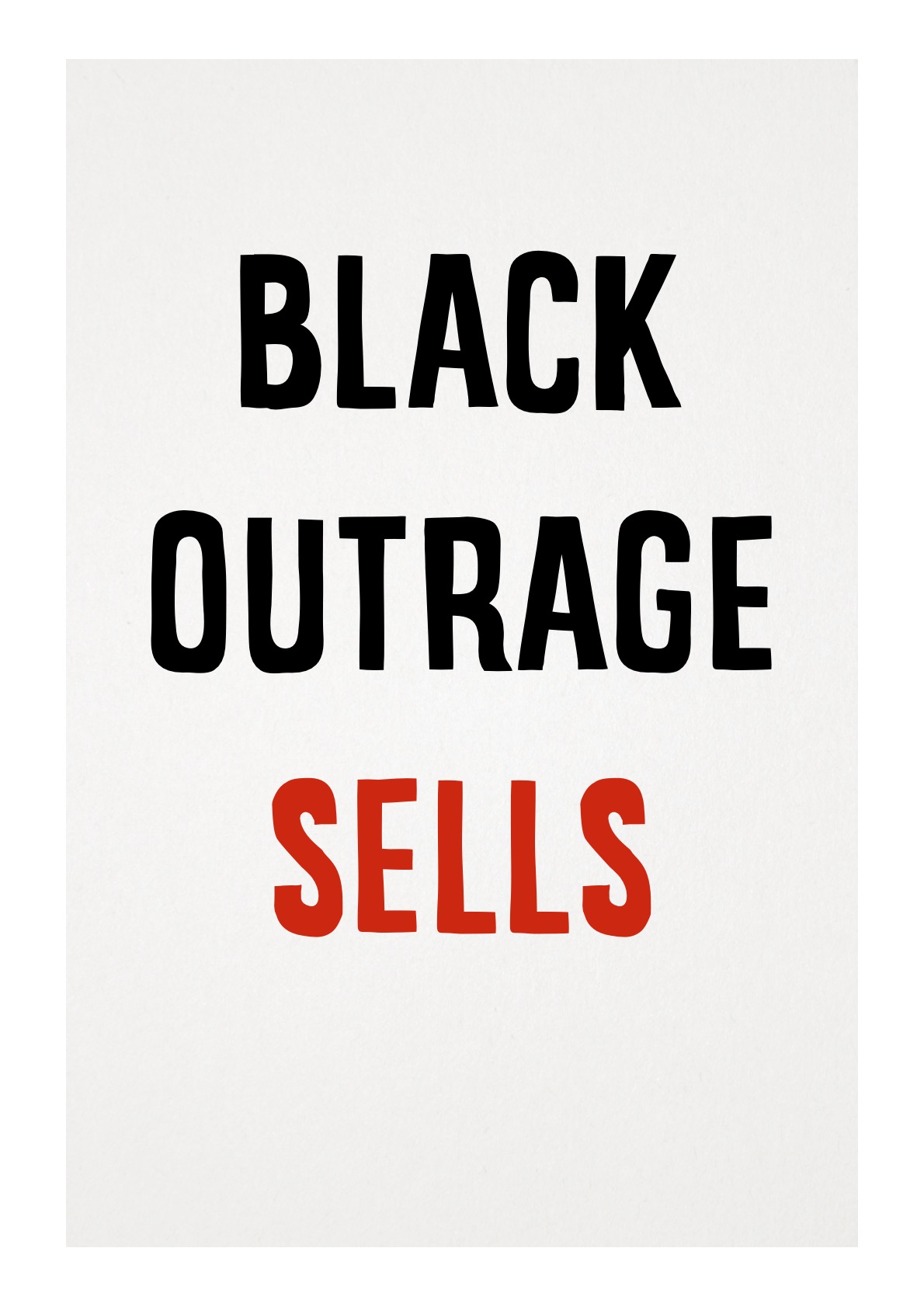

The artists contends that in art blackness is often packaged in stereotypes that confirm biases rather than allowing Black people to freely express themselves

The Three Balloons comes at a time when the news cycle is filled with reports of hate crimes perpetrated against Black gay men all over South Africa. Sphamandla Khoza, a 24 year old, was stabbed to death in Ntuzumu near Durban, and his body was found in a ditch near his home; in the Eastern Cape, Andile “Lulu” Nthulela, 40, disappeared for a week before his body was found buried at the home of a suspect; in Gauteng, Nathaniel Spokane’s body was found lifeless, with stab wounds in the chest.

Reports say these are just three of many such cases, with at least one being reported every month for the last year. It’s clear that in spite of the country’s celebrated recognition of queer rights as espoused in the Constitution, the reality on the ground for most queer Black men remains bleak at best. It’s difficult to look at K.Skit’s work outside of this context.

In ‘Mmele’ one of the videos from the series, K.Skits can be seen vogueing - a type of dance that is synonymous with New York City’s ball culture as seen in Paris is Burning. ‘Mmele’ means body in the artist’s native Sepedi language and the vogueing, drawn straight out of Paris is Burning, is characterised by hand gestures and body movements the artist sees as an apt depiction of liberation and the conjuring of alternative universes where his emancipation is not tethered to any particular gaze outside of his own.

The queer ball scene informing K.Skit’s ideas around liberation has become popular around the world as an outlet for queer youth in their quest for ‘safe spaces’ within which to express their queerness outside of the hetero-patriarchal norms of modern society. They often dress in drag and participate in dance-offs for a predominantly queer audience as a way of escaping the norms that often render their identity and expressions undesirable – or unpalatable.

As the artist notes, the rejection of queerness within Black communities and society at large, not only makes it difficult for many to exist without fear, it strips one of identity and often leaves queer youths to find alternative communities and ways of celebrating who they are.

“Traditional dancing is not my experience and a lot of Black sub-cultures are not relevant to my experience,” the artist says of their decision to use vogueing as an expression of that identity rather than, say, a traditional African dance or minno was setšo (indigenous African music). “When I was in high school, I discovered Paris is Burning and I binged it for a week because I identified with that desire for free expression. I took from it how free people in the film were when they were on the ballroom floor but I also just like viewing the world as a stage. You can create an alternative universe of your own through art and performance.”

The work Outrage by K.Skit touches on the manner in which ‘blackness’ is packaged and consumed and made palatable for the white gaze.

A self-taught artist, K.Skits has been dancing as early as eight years old. After a few years of doing sports in school, he eventually joined the drummies – or drum majorettes – and continued to dance through high school. After matriculating and finding an internship doing social media at Wits University, K.Skit’s became interested in photography and began to experiment with self-portraiture and making short dance videos on his smartphone.

The Three Balloons marks a continued expansion of this expression. He adds of his interest in art and ever developing multi-disciplinary practice that also includes DJ’ing: “Art feels to me like something that gives me room to express and create universes that don’t exist. It allows me to communicate in a different way, on my own terms and to create a different version of myself.”

- African Art Features Agency funded by the National Arts Council of South Africa.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory