Interview with Japan-based curator and collector Dexter Wimberly

Latitudes’ Chelsea Selvan caught up with Dexter Wimberly, the American entrepreneur and Hayama, Japan–based curator redefining contemporary narratives.

Dexter Wimberly is the co-founder of the online education platform CreativeStudy.

Wimberly has organized exhibitions in galleries and museums around the world including the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, The Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas, BODE in Berlin, The Harvey B. Gantt Center in Charlotte, The Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco, KOKI Arts in Tokyo, and The Third Line in Dubai.

His exhibitions have been reviewed and featured in publications including The New York Times and Artforum, and have received support from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and The Kinkade Family Foundation.

Wimberly is a Senior Critic at New York Academy of Art, and the founder and director of the Hayama Artist Residency in Japan. Prior to his curatorial career, Wimberly was the managing partner of the New York-based advertising and marketing agency August Bishop, representing a diverse array of clients including Adidas, The Coca-Cola Company, and HBO.

Explore the interview below.

------------------------

Latitudes Online (LO): You've brought together artists whose practices span Africa, Europe and the U.S., yet the exhibition's ideas feel universal - transformation, resilience and renewal. Why did you feel now was the right moment to explore these themes through African and diasporic voices, and why in Dubai? And what guided your curatorial thinking in bringing these particular artists into conversation?

Dexter Wimberly (DW): I think we're living through a moment of profound uncertainty — politically, environmentally, culturally. And when you're in that kind of turbulence, it's easy to feel like you're just waiting for whatever comes next. But these six artists — El Anatsui, Carrie Mae Weems, Abdoulaye Konaté, Yinka Shonibare, Iman Issa, and Adam Pendleton — remind us that we're not passive observers. We shape what's ahead through conscious decisions and deliberate actions. Every work in this show began as an idea in the artist's imagination before becoming tangible reality. That process itself is an assertion of agency.

As for timing and location: Dubai's position as a global crossroads makes it an ideal setting for this conversation. The city sits at the intersection of Africa, the Middle East, and the broader Global South. There's an openness here, a hunger for new narratives. Efie Gallery, with its mission rooted in the concept of "home"—efie in Twi—has created exactly the kind of environment where diverse global voices don't just coexist but genuinely converse with and enrich each other.

What drew me to these particular artists is that they all work at the junction between historical memory and contemporary urgency. They're not just documenting change—they're actively participating in shaping it. Shonibare and Issa both interrogate how historical narratives are constructed and who gets to tell those stories. In a place like Dubai where identity is already hybrid, where colonial histories intersect with contemporary global capital, these questions resonate powerfully. Anatsui transforms discarded materials into new cultural narratives that transcend borders. Konaté grounds urgent global concerns in the deeply local language of West African textile traditions. Pendleton uses Black Dada to merge radical experimentation with the politics of representation. And Weems' 1993 Africa series remains remarkably prescient in its examination of how power and memory are encoded in built environments. Their practices converge in a shared insistence on art's capacity to both witness and catalyze transformation.

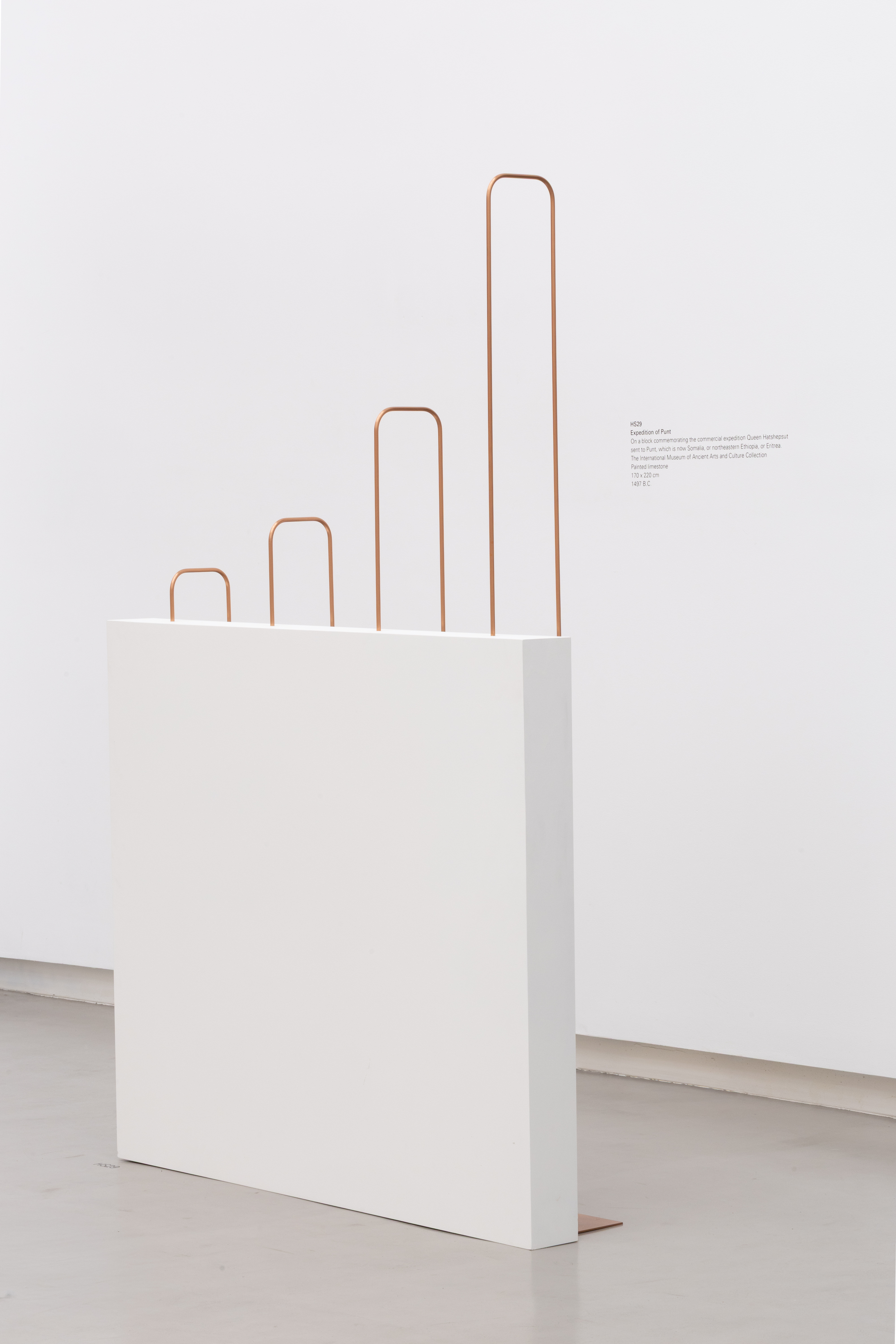

Install view, The Shape of Things to Come, Efie Gallery, Dubai, 2025.

LO: Dubai has become a hub for collectors and institutions interested in art from Africa. What kinds of conversations do you hope this show sparks among Middle Eastern and African audiences?

DW: I hope it generates conversations about belonging, authenticity, and how we define heritage in a globalized world. One of the most fascinating aspects of showing this work in Dubai is that the city itself embodies many of the tensions and possibilities these artists explore. It's a place of rapid transformation, where diverse cultures converge, where tradition and innovation exist side by side.

For Middle Eastern audiences, I think works like Issa's Heritage Studies offer a powerful entry point. She destabilizes the authority of historical objects by stripping them of specific temporal and geographic origins, asking: what survives from the past and how are those remnants reshaped in the present? That question is deeply relevant in a region with such layered histories.

Install view, Iman Issa, The Shape of Things to Come, Efie Gallery, Dubai, 2025.

For African audiences and those from the diaspora, I hope the exhibition affirms that African and diasporic voices are central to shaping global culture and contemporary artistic discourse—not peripheral to it. When you see Konaté's monumental textiles or Anatsui's shimmering sculptures, you're witnessing practices that are simultaneously rooted in specific cultural traditions and universally resonant. These aren't artists translating their work for Western audiences; they're working from positions of strength and clarity about who they are.

And for everyone, I hope the show prompts reflection on this fundamental question: Who gets to tell these stories? What gets preserved and what gets forgotten? In an era where narratives are constantly being rewritten—sometimes authentically, sometimes not—these artists model what it means to engage with history rigorously and imaginatively.

LO: The Kyoto Retreat and The Shape of Things to Come both foreground slow, intentional artistic inquiry. How do you balance that slower process of thinking and making with the pace and visibility demanded by today's art world?

DW: This is something I think about constantly, especially since founding the Hayama Artist Residency and now The Kyoto Retreat. Over the years, I've had conversations with hundreds of artists, and one thing that stands out is that nearly everyone is pressed for time. For artists, a lack of time is detrimental to career development, mental health, and the quality of work they can produce.

The residency programs are my attempt to create an antidote to that pressure. I want to give artists the time and space necessary to slow down, take stock, and make plans for the future. When I was unexpectedly living in Hayama for three months during the pandemic, I experienced firsthand how profound that slowing down can be. Being there made me feel safe when the rest of the world seemed to be falling apart. I developed a more intimate relationship with the place, and I realized this was something I needed to share with others.

But here's the thing — it's not about rejecting visibility or the professional demands of the art world. The Hayama Residency includes an exhibition and meetings with curators and gallerists in Japan. It's a real career-building opportunity. The Kyoto Retreat offers the same balance. The goal is to create space for quiet reflection while also opening doors.

As for my curatorial practice, I try to embody that same philosophy. When I'm working on an exhibition like The Shape of Things to Come, I'm not interested in rushing to follow trends or creating spectacle for its own sake. I'm interested in artists whose practices have depth, who've been thinking deeply about their work for years or decades. That slower, more intentional approach produces work that endures. And ultimately, that's what matters — not being the loudest voice in the moment, but creating something that will continue to resonate.

Install view, Carrie Mae Weems, The Shape of Things to Come, Efie Gallery, Dubai, 2025.

LO: You've curated internationally while maintaining a strong connection to artists from Africa and the diaspora. How do you navigate curating these narratives within global contexts - and what responsibilities come with that?

DW: I take this responsibility very seriously. I grew up in Brooklyn in the 1980s — in Bedford-Stuyvesant specifically — and that shaped me profoundly. I witnessed both the beauty and the struggle of that time and place. When I entered the art world, I came with a clear sense of purpose: I wanted to work with artists who reflect our times, who bring the beauty of under-exposed aspects of modern life to a greater public. I feel that this is my calling within the arts.

Curatorially, I focus on contemporary urban history and on practices that have been historically marginalised or misunderstood. That means presenting their work in ways that honor both specificity and universality. When I curated Black Abstractionists From Then 'til Now at the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas, the goal was to show how Black artists have been pushing abstraction forward for over a century—not as a response to European modernism, but as an independent, generative force. That exhibition included 38 artists from Frank Bowling to Jack Whitten to Rashid Johnson. The responsibility there was to show the breadth and depth of these practices without flattening their differences.

In a global context, the responsibility also includes being thoughtful about where and how work is shown. Dubai is strategically important because it's a bridge between Africa, the Middle East, and the Global South. Working with Efie Gallery, which was founded by a Ghanaian family and explicitly centers belonging and identity, means the geographical context supports the work rather than tokenizing it.

I also think there's a responsibility to younger artists and curators. That's why I am a Senior Critic at the New York Academy of Art, and why I run these residencies. It's about creating pathways, opening doors, sharing resources. Curating has always been a gateway for me — it's about building lasting relationships with artists and creating opportunities for them to thrive.

LO: At Latitudes, we think a lot about how digital and physical platforms can build bridges between artists, collectors and curators across regions. From your perspective, what does a truly global, interconnected art ecosystem look like - and what role do you see curators playing in it?

DW: A truly global ecosystem would be one where geography doesn't determine access or legitimacy. Where an artist in Lagos or Cairo or Tokyo has the same opportunities to develop their practice, show their work, and connect with audiences as someone in New York or London. We're getting closer to that in some ways — digital platforms have democratized visibility, and institutions in places like Dubai are creating new centers of gravity. But we still have a long way to go.

The digital component is crucial, but it can't replace physical encounters with art. There's something that happens when you stand in front of one of El Anatsui's sculptures — the way light moves across the surface, the tactile sense of weight and fragility, the scale — that you simply can't replicate on a screen. Similarly, the social dimension of the art world — the conversations that happen at openings, the relationships built over studio visits — still requires embodied presence.

El Anatsui, 5.63° N, 0.00° E, 2025, aluminium bottle caps and copper wire, 270 cm x 200 cm, courtesy the artist and Efie Gallery, Dubai.

So I think the ideal is a hybrid model. Digital platforms can build awareness, create initial connections, facilitate research. But they need to lead to physical encounters. That's partly why I'm so invested in residency programs. The Hayama Artist Residency and The Kyoto Retreat bring people from all over the world to Japan for sustained periods of time. That's where real exchange happens—not in a quick Instagram scroll, but in four weeks of living and working alongside other artists, engaging with a different culture, having time to think.

As for the curator's role in this ecosystem: I see us as facilitators, connectors, translators. We help artists reach audiences who might not otherwise encounter their work. We create contexts that allow work to be understood more fully. We build bridges between local and global, between different artistic traditions, between artists at different stages of their careers.

But I also think curators need to be willing to challenge existing power structures, not just reproduce them. That means being intentional about which narratives we amplify, which artists we champion, where we choose to show work. It means recognizing that institutions in Dubai, Lagos, Johannesburg, or São Paulo can be just as important as those in New York or London. It means understanding that the canon is always being written, and we have a responsibility to shape it more inclusively.

Ultimately, I'm optimistic. I see younger curators who are incredibly thoughtful about these questions. I see institutions becoming more globally minded. I see collectors who genuinely want to support diverse practices. And I see artists who refuse to be limited by geography or category, who are building their own networks and platforms. That's the ecosystem emerging — one that's more connected, more equitable, and more dynamic than what came before.

Dexter Wimberly picks his top three works on Latitudes

"Raubenheimer's Flood under Orion masterfully employs charcoal, graphite, and coloured pencil to create a haunting meditation on ecological vulnerability, where the celestial constancy of Orion bears witness to terrestrial inundation with devastating poetic force. The work's layered erasure and mark-making techniques evoke both the gradual processes of environmental degradation and the urgent immediacy of climate catastrophe, demanding sustained contemplation from viewers willing to confront our collective responsibility to the natural world."

"This luminous work masterfully captures the tension between upheaval and regeneration, with Boka's layered technique creating an almost alchemical transformation where botanical forms dissolve into pure light and color. The painting's delicate balance of vulnerability and vitality speaks to the profound poetry of adaptation, making it an essential addition to any collection exploring contemporary perspectives on ecology and metamorphosis."

"Raubenheimer's Flood under Orion masterfully employs charcoal, graphite, and coloured pencil to create a haunting meditation on ecological vulnerability, where the celestial constancy of Orion bears witness to terrestrial inundation with devastating poetic force. The work's layered erasure and mark-making techniques evoke both the gradual processes of environmental degradation and the urgent immediacy of climate catastrophe, demanding sustained contemplation from viewers willing to confront our collective responsibility to the natural world."

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory