FEATURE: On K Sello Duiker, Damien Hirst, and Mountain Retreats

A feature by Ashraf Jamal for ArtThrob

My dog and I are in ‘K Sello’ (Duiker), my daughter next door in ‘Herman’ (Charles Bosman). We’re at McBains in Bainskloof, a mountain retreat co-owned by Justin Nurse and Ma’ayan Hamiltion. He — K Sello — is a long-lost, long-dead friend and author of the most significant South African novel of the last 30 years, The Quiet Violence of Dreams. Pre-woke, Duiker’s novel has an honesty few comprehend today. He saw the rise of ‘neo-black’ fascism and wrote the dirt on our pathological inheritance in a prose that is alive to a human perversity which most these days suppress, or worse, ‘cancel’. Revisionism is the new norm; the art world aglow with nuclear green sanctimony. Not something that Duiker would have approved of, well, not the desperate-contrite-faux sheen of care which generally accompanies the heist at least.

Then again, revisionism has greater merit than Damien Hirst’s toxic ‘Empathy Suite’ in the Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas. At $100,000 a night, it is the most expensive on earth, replete with two bull sharks in formaldehyde titled Winner/Loser and a bar—Here For A Good Time Not a Long Time—that’s packed with medical waste. Pumped with all the cynicism one associates with a Martin Amis novel, Hirst’s ‘Empathy Suite’ is a sick thought designed to shock and boggle the heart. In Las Vegas, nothing in fact stays; everything is news.

Damien Hirst’s Empathy Suite at Palms Casino Resort, Las Vegas.

Around a fire I relate the story of Hirst’s suite to Nurse. It’s my first getaway in six months. We were all held hostage, victims of a ‘class suicide’ and successful plot to bankrupt not only a national economy but human feeling, family, the need for hugs. In short, empathy. That Hirst should baptise his suite so calculatedly and so wrongly is a bilious reminder of how perverse words have become. Of course, one can ‘laugh it off’, as Nurse has done, but sick wit cannot dispel the fact that ours is a venal and heartless age in which revisionism — throwing good will after bad — is little too late. I think Duiker would agree. I recall the two of us in a bar in Noordhoek a few months before he killed himself. We were at the Miramax Scriptwriting Workshop. Medicated to the gills, he was nevertheless utterly alert and warm. There was a fullness there, despite the shot rigging. He must have known, despite his gentle modesty, that his ballsy, brilliant, overwritten novel would last forever.

That his name would be consecrated in a mountain retreat is another matter. Nothing Hirst ever created could warrant such grace, though Nurse informs me that his personal encounter with the insufferable brat was heartening. They’d met in a rehab centre in Cape Town where Hirst’s girlfriend was billeted, and Nurse worked as a councillor. Cape Town is a rehab mecca. I once met a man in a café in Observatory who’d quit New York for Cape Town in a desperate attempt to save his nose, whose function and form had been destroyed by coke. Gentle, elegant, and tragic, he spoke to me of Buddha. Reflecting on this meld of addiction and grace, it seems a fallible compound of a gone era. Today one is exercised by or subject to extremes. Grace is a dead idea. As is empathy. There is no relief from hypocrisy, cruelty, rage. Hirst’s ‘Empathy Suite’ sums up the callowness and callousness of our age.

![Kemang Wa Lehulere, Once bitten, twice shy [Detail], 2016. Salvaged school desks, dentures, gold-leaf-covered books, steel](/media/0ial5qvm/kemang-wa-lehulere-once-bitten-twice-shy-detail-2016-salvaged-school-desks-dentures-gold-leaf-covered-books-steel.jpeg)

Kemang Wa Lehulere, Once bitten, twice shy [Detail], 2016. Salvaged school desks, dentures, gold-leaf-covered books, steel

Nurse tells me that when he is not in Bainskloof he lives in a complex in Muizenberg, which he manages. He is, as they say, a ‘people person’. His neighbour is Kemang wa Lehulere, which intrigues me, given that I’d chatted with Wa Lehulere at Café Ganesh the night before. Despite my disgust in the face of a global inhumanity, I was profoundly moved by the artist’s ability to coax self-belief in a young tech whizz. Wa Lehulere listens, emboldens, restores heart. But as Nurse informs me, he is also a terrible parker, his vehicle out of joint, overstepping the grid, wild in its disregard for propriety and form, which is unsurprising, given his art and vision. I’ll be visiting the artist’s studio when I get back to the city. Now, however, it is Nurse who holds my attention.

Nurse has just emerged into the lounge to settle by the fire, having read the book he hands to me, How To Change Your Mind, The New Science of Psychedelics by Michael Pollan who, ‘under the influence of toad venom, becomes convinced he’s giving birth to himself.’ The sentiment is fitting: what else is left to do? Given a global rage that has metastasized, how does one nurture, engender, self-create? If there is precious little room to translate a good feeling — if ours is a time tin-eared, tone deaf, bereft of subtlety — imbibing some toad venom is clearly a good thing. For all my gloom, my rabid despair, I cannot fault the need for decency, kindness, grace. It’s why I’m installed in my personal empathy suite, K Sello, huddled about a fire, mountain water pounding through the gully beneath.

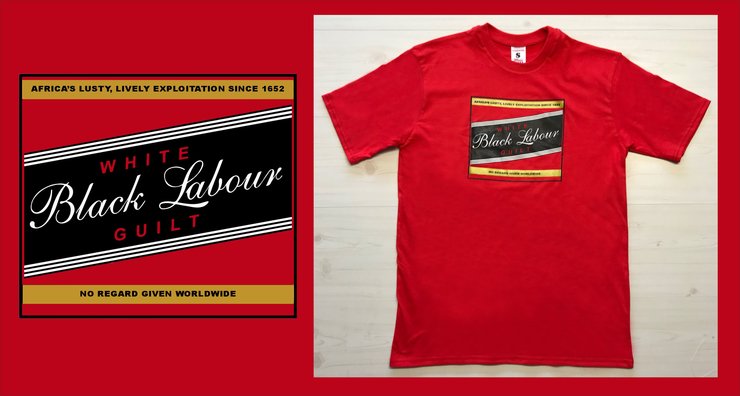

Laugh It Off’s infamous Black Labour spoof t-shirt

Between 2000 and 2005, Nurse was embroiled in a now legendary legal battle which centred on his spoofing of twenty brands, most notoriously his tagline, ‘BLACK LABOUR WHITE GUILT.’ A riff on SAB’s beer, Black Label, Nurse was charged with ‘hate speech’, of ‘not exercising freedom of expression but abusing it.’ It’s day two of my stay and we are seated on deck overlooking the thudding river, fluffy blankets about our shoulders. ‘Satire is still a form of art I guess,’ Nurse muses, though he remains uncertain. Ours is a humourless time; ‘brand spoofing passe.’ He had ‘more gumption and stomach then.’ We all did. ‘Now there’s no way of saying things without being castrated.’ Still, ‘against cancel culture and trolling we need healthy conversation.’ And if this seems well-nigh impossible, there’s always Nurse’s mountain retreat, where the ‘silence is so loud, the water so cold.’ Nurse has ‘an appetite for life.’ He plans to transform Bainskloof into a ‘lockdown pop-up space for art that inspires change.’ Peter van Straten is a much-loved favourite because of the artist’s humour and the beauty of the execution.

As we speak, McBains is undergoing a face-lift, its exterior walls transformed by two street artists, Sven Christian and Martin Lund. Christian is working on a tribute to Paul du Toit who, prior to his death, took his oxygen tank with him on a final getaway to an island in the Indian Ocean. Alongside the painting, Christian has added Du Toit’s words from a scrapbook — ‘No one is going to do it for you.’ The sentiment is bracing, especially now that we are all indentured, co-opted, denied the right to speak our minds. But there, in that mountain retreat in Bainskloof — its access road built by prisoners and engineered by Andrew Geddes Bain (1797–1864) — it seems as if it’s still possible, even if Nurse has doubts as to what can and can’t be spoofed. K Sello Duiker, universally celebrated, and Paul du Toit, still maligned by art snobs, live on. Answering his own question — ‘How important is art in these times?’ — Nurse reminds us that art, and the life we create to make it possible, still ‘inspires change,’ if you have the ‘appetite.’

Here I find myself returning to Nurse’s best-known slogan, ‘BLACK LABOUR WHITE GUILT’. Its currency persists, though who, supposedly, has the right to speak in its name skews the slogan’s integrity. As Christian reminds me, ‘white guilt obstructs the possibility of actually acknowledging or dealing with indentured black labour. The target of that slogan is whiteness; Hirst’s suite and brand.’ But I can’t help thinking about another slogan, engineered by a UK PR company in 2014, which cynically chose to exploit rather than address guilt — White Monopoly Capital. The phrase is on all of our tongues these days. Its objective is to entrench division, not resolve it. If Nurse’s barb is heartfully witty, this one is chilling.

It’s the final morning of my stay. With my dog Mica in tow, I walk along the winding tarred road. Mist greets me and swirls away, the rocky flank to my right awash with mountain water. The sky steadily parts. Why be gloomy on God’s day?

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory