Encountering fiction in South African works of art

Mary Sibande, Her Majesty, Queen Sophie, courtesy of the artist

Encountering fiction in South African works of art

Art and artists make for good stories. Over the years, a rich relationship between South African art and fiction has emerged, with art serving as a point of inspiration for fictional narratives.

The same can be said of the inverse. In the hands of the artist, fiction can become a creative strategy or methodology, a tool for problem-solving, generating new material, developing a conceptual point of departure, or grappling with complex ideas and heavy histories in novel ways.

While many South African artists draw on mythology and folktales from the continent, my interest here is restricted to those artists who choose to generate or draw on wholly fictionalised narratives, or who choose to fictionalise their realities, in the making of their work.

Lending narrative to material form

I keep a postcard pinned to the corkboard above my desk. It shows a small sculpture – a pair of legs with no torso – by the visual artist Rhett Martyn. I like to keep it around to remind me to be wary of the origins of a story.

In 2018, I attended an exhibition walkabout[1] by Martyn at David Krut Gallery for his exhibition, 1:10 Modernist Plunder: The New Constructivists. Martyn had produced a series of maquettes for the exhibition – small paper sculptures made to look like patinaed and rusted metal that sat in a replica model of the gallery space. They were curious things, impeccable imitations found to be nothing but paper when you picked them up and felt their weightlessness in your hands. In retrospect, this was a clue.

Rhett Martyn's 1:10 Modernist Plunder: The New Constructivists. Images courtesy of David Krut Gallery.

Rhett Martyn's 1:10 Modernist Plunder: The New Constructivists. Images courtesy of David Krut Gallery.

After inviting us to engage with the works, Martyn launched into the story of João Mangual, whose life and death served as the inspiration for this body of work.

The story goes like this: João Mangual was a prominent Mozambican businessman, architect and art patron who was involved in the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) in the 1960s and 70s. He was invested in the South African anti-apartheid struggle, too, and was a strong supporter of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC). An eloquent speaker and a man of many languages, Mangual frequently liaised with FRELIMO members as well as Russian dignitaries, which saw him making several trips to Russia. Being both an architect and an art-lover, he had a particular interest in Modernist sculpture and began building up a collection of pieces from artists working in the style of Russian Constructivism. In 1978, after shipping a number of these works back to Mozambique, Mangual decided he wanted to showcase his collection in a public exhibition.

Johannesburg, being an artistic and cultural hub at the time, was a good place to do so. Arriving in the city, he made contact with a prominent art dealer and organised an exhibition. He also made contact with a few MK operatives and hatched a plan to smuggle weapons, with the help of FRELIMO, from Mozambique to South Africa by concealing them inside the sculptures that would be exhibited. It’s alleged that a spy from the National Party was at this meeting between Mangual and MK and a few days later, not far from where the meeting took place, Mangual was found dead in the Jukskei river.

Martyn’s works, a reconstruction in miniature of Mangual’s lost exhibition, now became all the more profound. He let the story settle for a while before breaking the silence.

“Right,” he said. “That’s the story. I’ve fabricated the entire story.”

We’d been tricked. Like any good story, Martyn’s was close enough to reality to be completely plausible. Former Constitutional Court judge Albie Sachs, during his exile years in Mozambique, built up a collection of African art while also befriending South African struggle artists such as Dumile Feni, for example. The exile stories of musician Hugh Masekela and the Medu Art Ensemble’s Thami Mnyele resonate, too.

For Martyn, who felt he had become too caught up in replicating a particular Modernist tradition, the use of a fictional narrative became a way to both solve a creative block, and to rationalise and validate a set of material works.

Autofictions and collective narratives

The use of fictionalised autobiographical elements in a work of art can be a way of speaking to universal conditions through personal experience. For the artist Mary Sibande, this way of working has given life to the character of “Sophie”.

In her earliest bodies of work, through to her most recent, the interdisciplinary artist has conjured the “alter-ego” figure of Sophie. Modelled after Sibande’s likeness, Sophie is a sculptural, performative, and enduring representation of the lived realities of her maternal line, while also speaking to a broader history of Black women’s labour and sacrifice in South Africa.

Here, fiction is employed as a thin veil for personal narrative, and a vital receptacle for a collective story. Importantly, as evolving characters in an ongoing body of work, Sibande’s many “Sophies” continue to develop the story, keeping history active, alive, and in the process of being written.

Mary Sibande, Her Majesty, Queen Sophie, courtesy of the artist

Mary Sibande, Her Majesty, Queen Sophie, courtesy of the artist

Fiction as critique

The commercial art world provides ample material for storytellers and satirists. Cape Town-based artist Mitchell Gilbert Messina is both. In 2017, the artist produced a series of comedic drawings he compiled in a video work titled Big Old Drawings.

The result is a collection of wry flash fiction that follows a downtrodden artist who interacts with an anonymous, imposing gallerist and comes out worse for it. In one cartoon, a pair of disembodied hands (the gallerist’s) emerge from the gallery space. The artist waves back at them. “Nice [of you] to pop by” reads the caption in frame one. ‘We put your name up outside,’ the gallerist continues in frame two, “so you can see it without coming in.”

Another of Messina’s video works that speaks to the relationships of power between artist and gallerist, or artist and institution, is A Brief History of the Institute. Exhibited as part of the group exhibition, shady tactics, at Cape Town’s smac gallery, the work uses images sourced from the internet as well as sound and text, to create a fictional narrative rooted in the reality of South African contemporary art. The piece tells the tale of an art institute with a questionable history and an agenda of rampant cultural extraction. The institute is anonymous, of course, but associations abound (there is that museum in the Waterfront, and the other one in Tokai).

As the exhibition statement put it, A Brief History of the Institute is a work “alluding to consumerist desire and the ‘cultural mining’ tendency of the neoliberal art world, which reproduces new trends but spews the same power relationships,”[2]

Journalists and cultural critics might help in providing a reliable record of events, but it is the kind of playful and pointed fiction by artists such as Messina that provides us with another point of entry, and another way of making sense of it all.

World-building

At times, whole fictionalised worlds and narratives form the basis of a body of work.

If the late Walter Battiss had grown up to become a novelist, he might have found some success in a series of books about the utopian isle Fook Island. Thankfully, he became an artist instead.

Fook Island, Battiss’ “island of the imagination” was an amalgamation of the many islands he visited over the years, but it was also a manifestation of his creative practice and philosophy. Battiss developed language, alphabet, currency, postage stamps, maps, people, animals, history, passports and even driver's licenses for the imaginary realm.

It gave way to an extraordinary amount of art over the years. In his way, Fook Island might easily have been a fictitious studio space for the artist – a space for generative play and exploration.

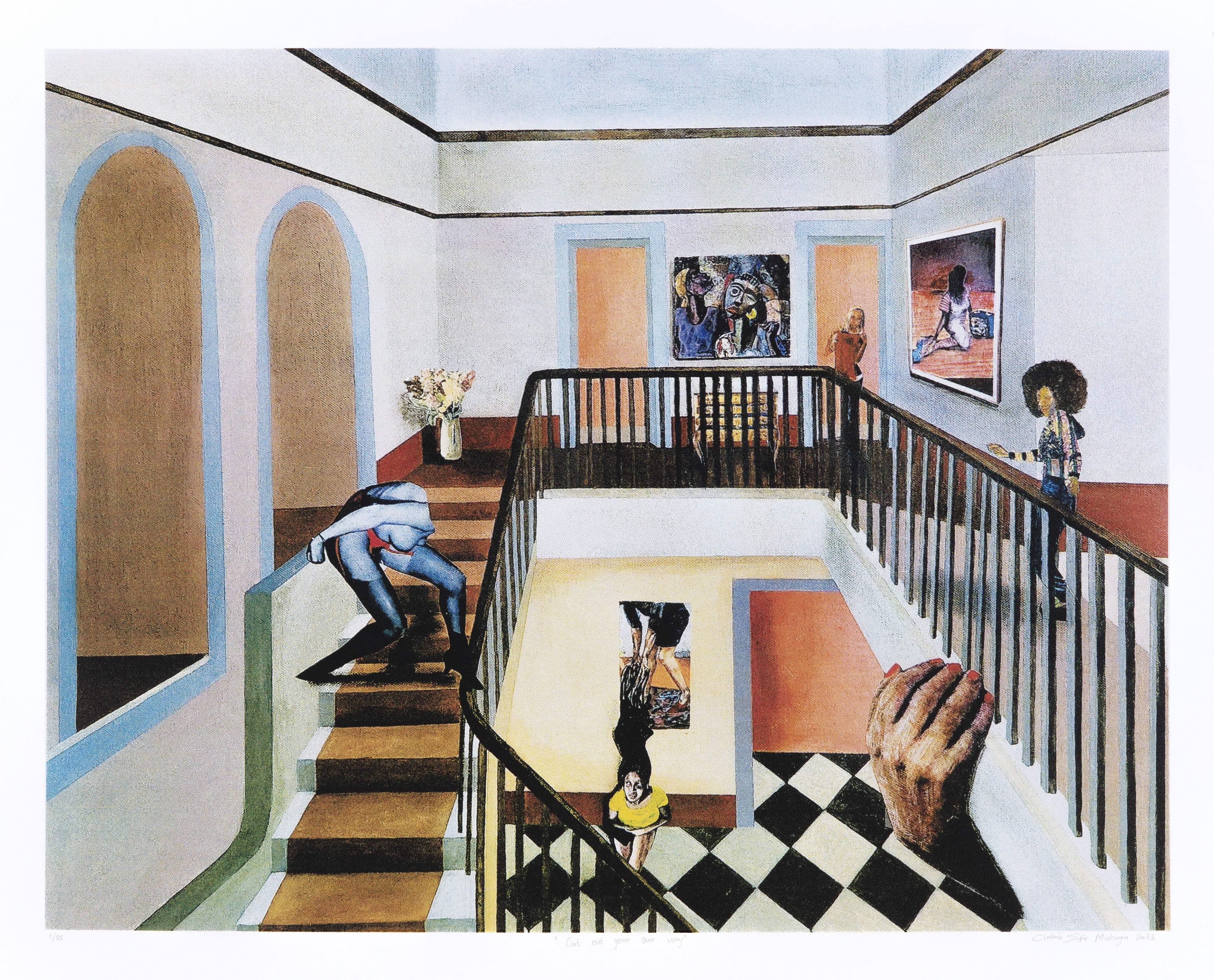

Other times, the tools and tactics of fiction are far more subtle in an artist’s practice. At first, it’s not clear that Cinthia Sifa Mulanga is making use of speculative narratives in her mixed-media works challenging Black female representation. But the fabrication of characters and the worlds they exist in is essential to her work and here we see various protagonists – sometimes drawn from popular culture, sometimes partly autofictional – inhabiting the frame. The spaces, with their Dreamhouse-like interiors, can even be seen as characters themselves – a symbolic extension of the individuals they hold.

Cinthia Sifa Mulanga, get out of your own way silk print, R25,000.00 excluding VAT, ENQUIRE

Cinthia Sifa Mulanga, get out of your own way silk print, R25,000.00 excluding VAT, ENQUIRE

Text features prominently in Mulanga’s work, too, but you need to search for it. Hidden inside objects or on cellphone screens, the collaged texts are drawn from beauty magazines and literary essays alike. Altogether these texts, art historical and popular culture references, worlds, and characters present short, sharp fictional realms.

Like a story, or a Dreamhouse, you’re invited to step into them, to immerse yourself, and to look back out at reality with a new perspective.

Fictional views of history

For his 2019 solo at Johannesburg’s Goodman gallery, Massive Nerve Corpus, Mikhael Subotzky generated an interview with a (thinly) fictionalised curator named Hansolo Umberto Oberist, which served as the exhibition statement. In it, “Hansolo” references Subotsky’s 2012 film, Moses and Griffiths and the artist’s discomfort with persistent historical imbalances.

“Would it be fair to say that the jump to fiction in your next film installation, WYE (2016), has to do with these discomforts?” he asks.

Subotzky replies: “There were a number of reasons for writing WYE as a fictional film. It was a kind of revelling, I guess, in the expanded opportunities the fictional form gave me in terms of the malleability of narrative time and space.”

WYE is an immersive three-screen film installation that follows three fictional protagonists travelling between England, South Africa and Australia, and their projections onto and preoccupations with these landscapes.

Still from Mikhael Subotzky's short film WYE, courtesy of the artist

Still from Mikhael Subotzky's short film WYE, courtesy of the artist

Even the most enduring chapters of history are at risk of growing stale in their recitation. In this way, fiction becomes an interesting tool for a (re)retelling of the past in ways that allow us to agitate or scratch at the surface of hard-worn narratives.

Certain characters have appeared and reappeared in William Kentridge’s ‘Drawings for Projection’ over the years. In his 1989 film, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris, we are introduced to two of them – the pinstriped industrialist Soho Eckstein, and the artist Felix Teitlebaum, both of whom have been said to vaguely resemble the artist himself – Kentridge has called Eckstein “a self-portrait in the third person” – although both characters have a storied and ultimately fictional provenance.

William Kentridge, Drawing for City Deep (Landscape with Projection Screen), 2019, Price on request, ENQUIRE

William Kentridge, Drawing for City Deep (Landscape with Projection Screen), 2019, Price on request, ENQUIRE

In his labour-intensive charcoal animation films, these characters become the medium through which we make sense of historical and contemporary South African life. Eckstein, with his cloud of cigar smoke and prospecting coffee plunger, has been the more prolific character over the years, appearing most recently in Kentridge’s 2020 film, City Deep.

Here, seeking refuge in a crumbling Johannesburg Art Gallery, surrounded by a desolated Highveld scoured by artisan miners, Eckstein once again becomes a cumulative fictional presence, this time reckoning with the heavy weight of history, and perhaps his own shifting conscience.

The artists and artworks mentioned here are not particularly known for their use of fiction in a visual art context, but through the process of embracing it as a tool in their practice, they’ve produced bodies of work that provide us with an idea of the generative potential of fiction in art-making.

As tools for making sense of an increasingly nonsensical world, art and fiction might be more essential than ever before.

David Mann is a Johannesburg-based writer and editor who writes at the intersections of art, architecture, performance and fiction. His book, Once Removed (Botsotso 2024), is a collection of short stories about South African art and performance.

[1] The full walkabout by Rhett Martyn is available on Spotify courtesy of the David Krut gallery: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2u8GRyITFECPeYDeONyMwA?si=rjWJ5NNaQ1eU0vx0TFSHnw

[2] As written by curator of the exhibition, Thuli Gamedze, in the exhibition statement: https://www.smacgallery.com/exhibitions-archive-3/shady-tactics

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory