Encountering South African artists in works of fiction

--------------------------

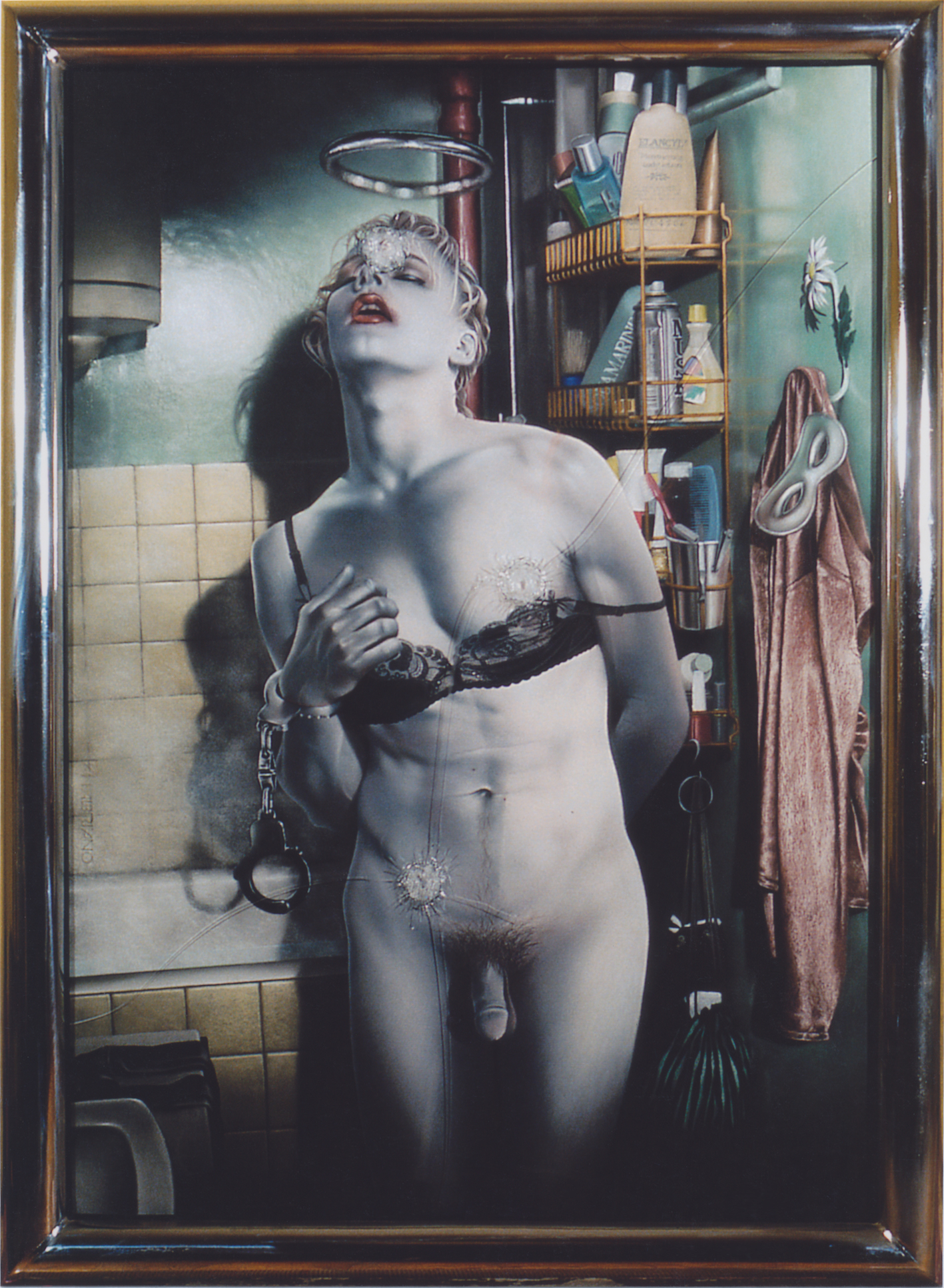

Marcus Glaser, untitled, courtesy: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Marcus Glaser, untitled, courtesy: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Writers and artists are frequent collaborators. Both use art, be it the written or the visual, as a means of making sense of the world – of communicating what it is they have to say about a particular moment, place, or set of conditions. Often, artists will use a work of fiction as a conceptual starting point for their work, or novelists will reference the work of a visual artist in their writing.

In the case of the latter, there is a decent amount of South African fiction that make use of art, artists and artistic institutions as characters, narrative devices or plot points. The novels and short stories of Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, Richard Rive, Sol Plaatje, Ivan Vladislavić and Ashraf Jamal are a few examples.

Andrew Putter and Tracy Payne in Ashraf Jamal’s Love Themes for the Wilderness

Writer and art critic Ashraf Jamal’s second novel, Love Themes for the Wilderness (1996) can be read as a work of fiction that muses on the state of South Africa’s art industry and the global attention it garnered in the early 1990s. Set in Cape Town, the novel follows a painter protagonist named Stoker.

“[Love Themes] is set in what I call the Bermuda Triangle – this magical moment where everything is possible – between 1990 and 1993,” Jamal told me in 2021. “This moment when certain things are open and possible, is the moment when we become aware of our potential in an international domain, how that’s going to happen, how we’re going to make it possible, but back then the galleries were not yet in place.”

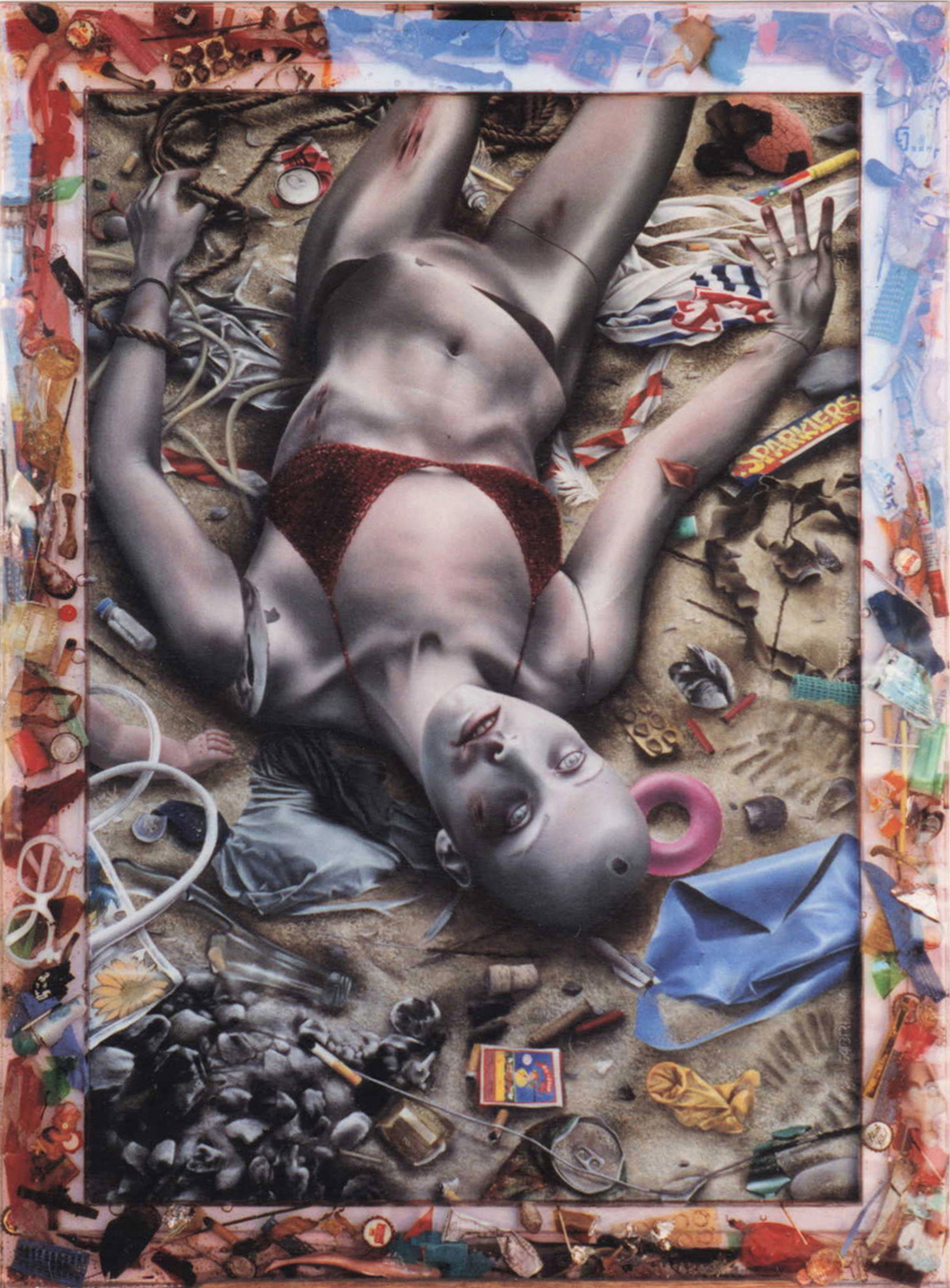

Tracy Payne, Sebastian (1994), 100 x 69 cm, Soft pastel on Fabriano Rosapina 300g, chromed steel frame, courtesy: Tracy Payne

The novel also touches on the ways in which queerness and sexuality were being experimented with through art at the time. One of the book’s characters, Putter, is working to develop art projects and ecosystems outside of the conventional gallery structures through ‘The Locker Room Project’ – a party as an artistic event.

Putter happens to be based on the Cape Town artist and educator Andrew Putter, co-founder of The Mother City Queer Project which, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, hosted a number of art parties and, as in the novel, aimed to use art projects and events as tools for rethinking identity, place and sexuality among other things, in a changing South Africa. Today, the legacy continues through contemporary art parties like Death of Glitter.

Tracy Payne, Coastal Resort (1995), 115 x 81 cm, Soft pastel on Fabriano Rosapina 300g, found objects and cast resin frame, courtesy: Tracy Payne

Then there is the work of the Cape Town-based painter Tracy Payne. A cropped version of Payne’s painting ‘Sebastian’ is used as the book’s cover and is also described in full in the novel, as is another painting by Payne, ‘Coastal Resort’. Both paintings come from her 1993 – 1995 series The Twilight Zone and are surreal and detailed works, equal parts macabre and compelling. Others who appear in the novel, albeit only as brief references or points of inspiration, are the South African artists Kevin Brand and Willie Bester.

Joachim Schönfeldt and David Goldblatt in Ivan Vladislavić’s The Exploded View and Double Negative

South African art and artists (specifically Johannesburg-based artists) feature in many of Ivan Vladislavić’s novels. In Portrait with Keys (2006) for example, the protagonist follows the gradual painting over of what he believes to be an Esther Mahlangu mural in the east of Joburg, while one of the sections comprising The Exploded View (2004) follows the fictional Greenside-based artist Simeon Majara who muses on the value systems at play in South African contemporary art markets, producing highly successful bodies of work through highly questionable ways of working.

While part of The Exploded View deals with a fictional artist, the overall novel’s inception is in The Model Men an exhibition by the artist Joachim Schönfeldt. Schönfeldt had produced a series of “illustrations for an unwritten text” and approached Vladislavić to respond with words. Vladislavić’s response quickly evolved into a full-length book of fiction. In this way, Schönfeldt’s illustrations run silently throughout the novel, from its artists, engineers and statisticians, to its night time highways, faux-Tuscan villas, and crudely themed restaurants.

David Goldblatt, She Said, "You Be The Driver And I'll Be The Madam", Jhb, 1975, Silver gelatin hand print, Courtesy the Goldblatt Legacy Foundation and Goodman Gallery

Then there is TJ and Double Negative (2010), a volume of photographs and a novel which emerged out of direct collaboration between Vladislavić and the photographer David Goldblatt. Both books speak to Johannesburg in all of its complexity, evoking the rocky koppies, the bustling inner-city, and the arcadian reaches of the suburbs. In TJ, Goldblatt drew on his extensive body of photographic work while in Double Negative Vladislavić gives us the story of two photographers – the young and aimless Neville Lister, and Saul Auerbach who serves as something of a mentor to Lister.

Goldblatt’s images (many of them with narrative-like captions) are not always directly responded to by Vladislavić’s novel, but some of them, like the title image of TJ, appear as novelistic devices. Together, the novel and the images serve as distinct yet complimentary reflections on the people and places that define the city, as well the act of photography itself.

Marcus Glaser and Santu Mofokeng in Bronwyn Law-Viljoen’s The Printmaker and Notes on Falling

Untapped archives animate the work of Bronwyn Law-Viljoen. In both of her novels, artists emerge and intersect, but it is the character of the relatively obscure, yet prolific artist that interests her.

In a recent talk with the artist Mikhael Subotszky on fiction and photography in her latest novel Notes on Falling (2022), Law-Viljoen mentioned how, whilst living in New York in the early 2000s, she came across Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album as exhibited by David Krut in 2004. It was a vital encounter. While the series of digitally reworked 19th century, colonial portraits of Black South African families doesn’t feature overtly in the novel, it provided the basis for Law-Viljoen’s thinking around working with the photographic archive. How temporality can influence one’s reading of a body of seemingly disconnected images, and what it means to be a photographer working with other people’s photographs, as is the lot of the novel’s protagonist, Thalia.

Marcus Glaser, untitled, courtesy: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

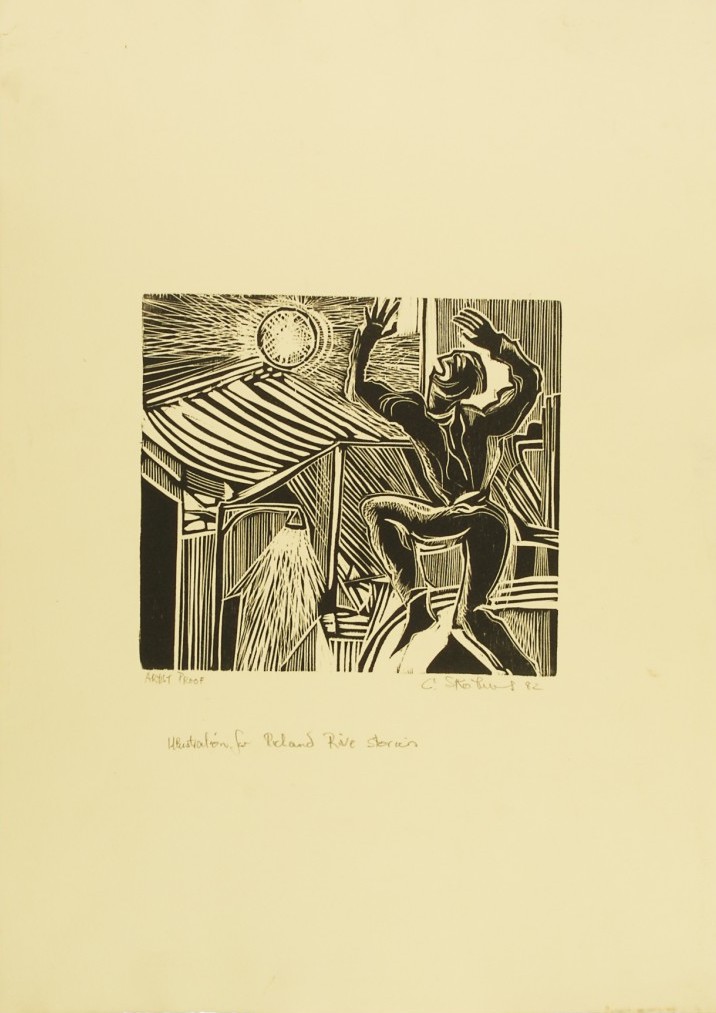

In her first novel, The Printmaker (2016), the life and work of the South African artist Marcus Glaser factor into the novel more directly. Following the artist’s death in 2007, Law-Viljoen came into possession of a significant amount of Glaser’s work. “This unlikely ‘inheritance’ simmered in boxes in my house for a long time – perhaps five years – before I embarked on my more formal engagement with it,” explains Law-Viljoen in an essay on Glaser.[1]

Marcus Glaser, untitled, courtesy: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Marcus Glaser, untitled, courtesy: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

The reclusive artist in The Printmaker, March Halberg, is based in part on Glaser who, despite his prolific output, was little known in commercial art circles, and gets only a few brief mentions in a handful of publications on South African art history. One of Glaser’s untitled lithographs also features as the book’s endpapers.

Cecil Skotnes in Richard Rive’s Advance, Retreat: Selected Short Stories and Sol T Plaatje’s Mhudi

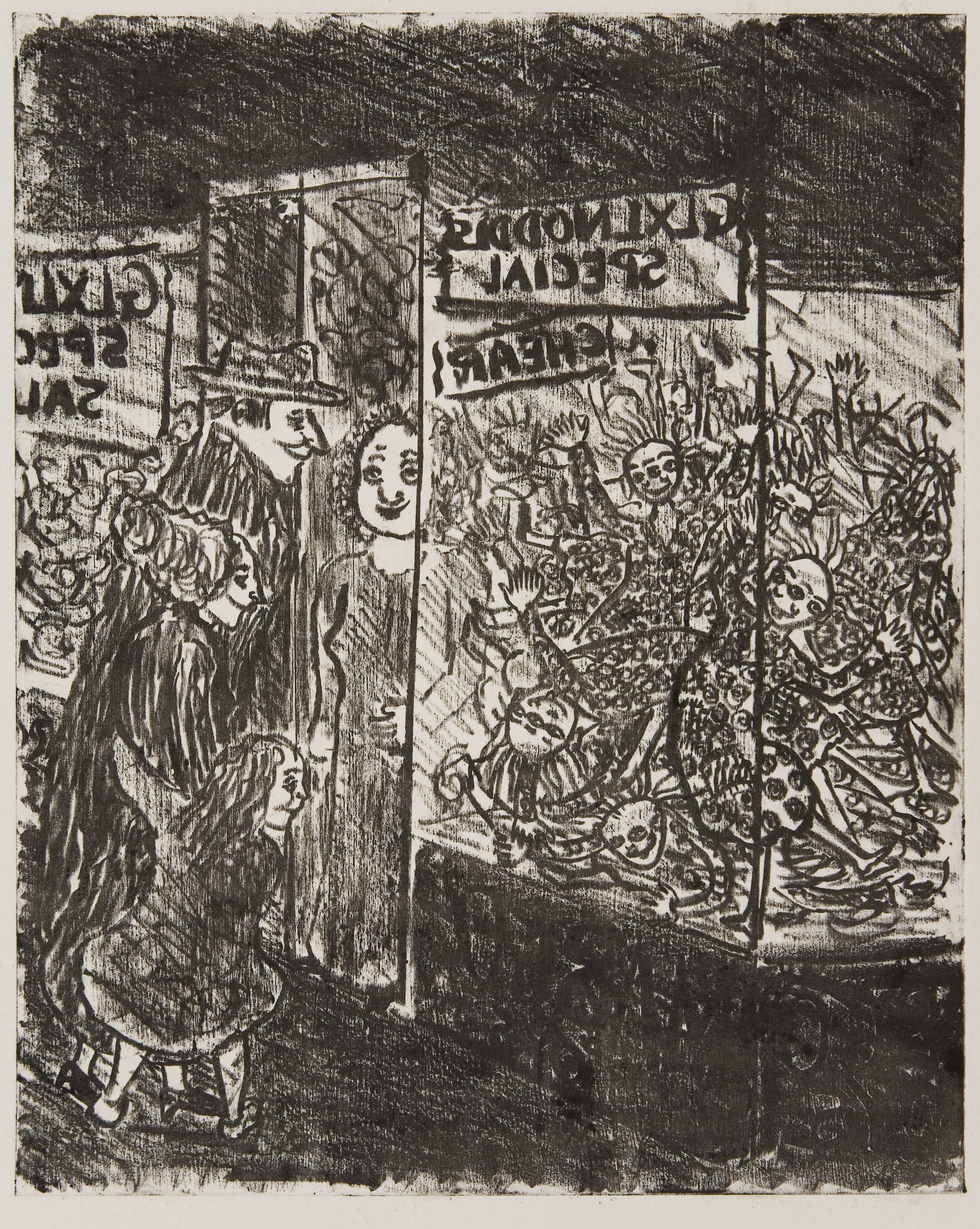

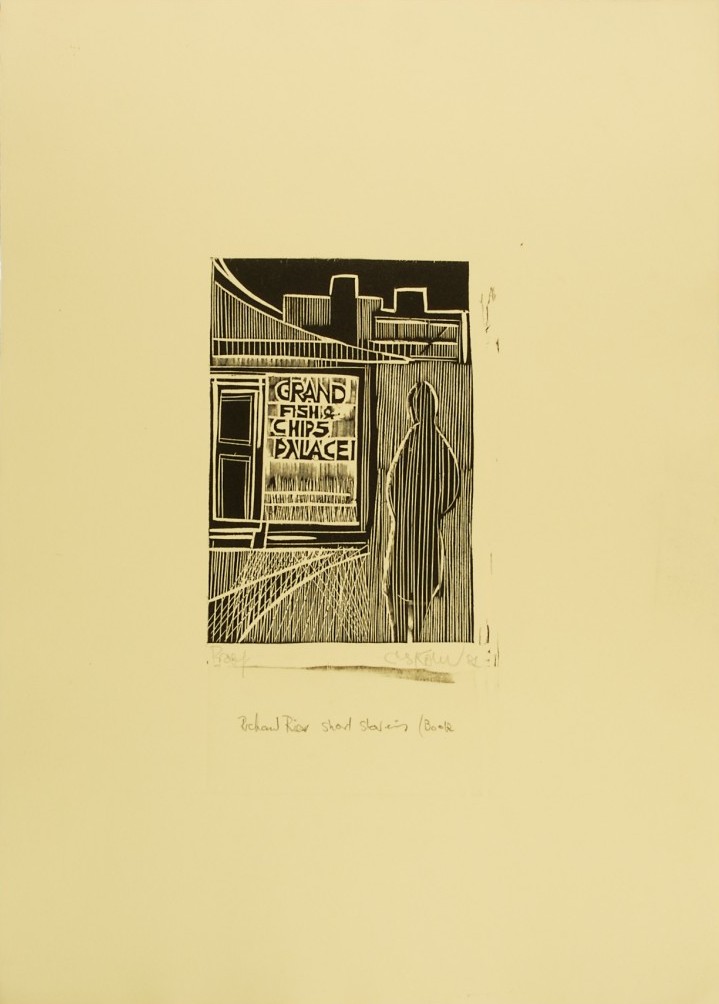

Finally, the work of Cecil Skotnes, who was well-known for his wooden panels and woodblock prints, features differently, but equally significantly in the work of the Cape Town-based writer and academic Richard Rive and the journalist, translator, and writer Sol T Plaatje.

In Rive’s collection of short stories Advance, Retreat (1983), each story is accompanied by a custom artwork by Skotnes. In a small moment from ‘Drive-in’, Rive also invokes Skotnes to better set the tone and period of the story:

The discussion had taken place at Mervyn’s flat, where he had been once before. Cheap wine, potato crisps and lots of smoke. Crude African mats on the floor with Skotnes prints on the wall. Rows and rows of untidy paperbacks. The discussion had continued interminably. The establishment of a multi-racial writers’ group. Or was it non-racial?[2]

Cecil Skotnes artwork for Advance, Retreat. Image courtesy of the Skotnes Family Estate

In Mhudi (1930), Plaatje centres significant African historical events and rewrites Eurocentric versions of African history. First published by Lovedale Press in 1930, the novel was republished in 1975 by Quagga Press, a project by the publisher Stephen Gray and Skotnes himself. Naturally, Skotnes created a series of accompanying artworks which are scattered throughout the book.

Plaatje draws on prophecy and the visionary dream through Mhudi, notably to predict the arrival of Halley’s Comet. In the endpapers of the Quagga Press edition, Skotnes interprets this dramatic and crucial symbol burning across the page, as if it’s about to tear through the margins and into the text.

Cecil Skotnes artwork for Advance, Retreat. Image courtesy of the Skotnes Family Estate

In the absence of the artworks and artists they draw on, the above works of fiction might have become very different texts. Or perhaps some of them would simply be read a little differently. All of them, though, benefit from the collaborative and generative act of welcoming visual art into their narratives.

- David Mann is a Johannesburg-based writer and editor who is interested in writing at the intersections of art, architecture, performance and fiction.

[1] Law-Viljoen, B., 2018. The caretaker of wounds: pictures of the deposition of Christ in the work of Marcus Glaser. Image & Text: A Journal for Design , 31(1). p. 89.

[2] Rive, R., 1983. Advance, Retreat. Cape Town: David Philip. p. 50.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory