Documenta 15 is a global-south-centric event, but who is its intended audience?

-------------------------

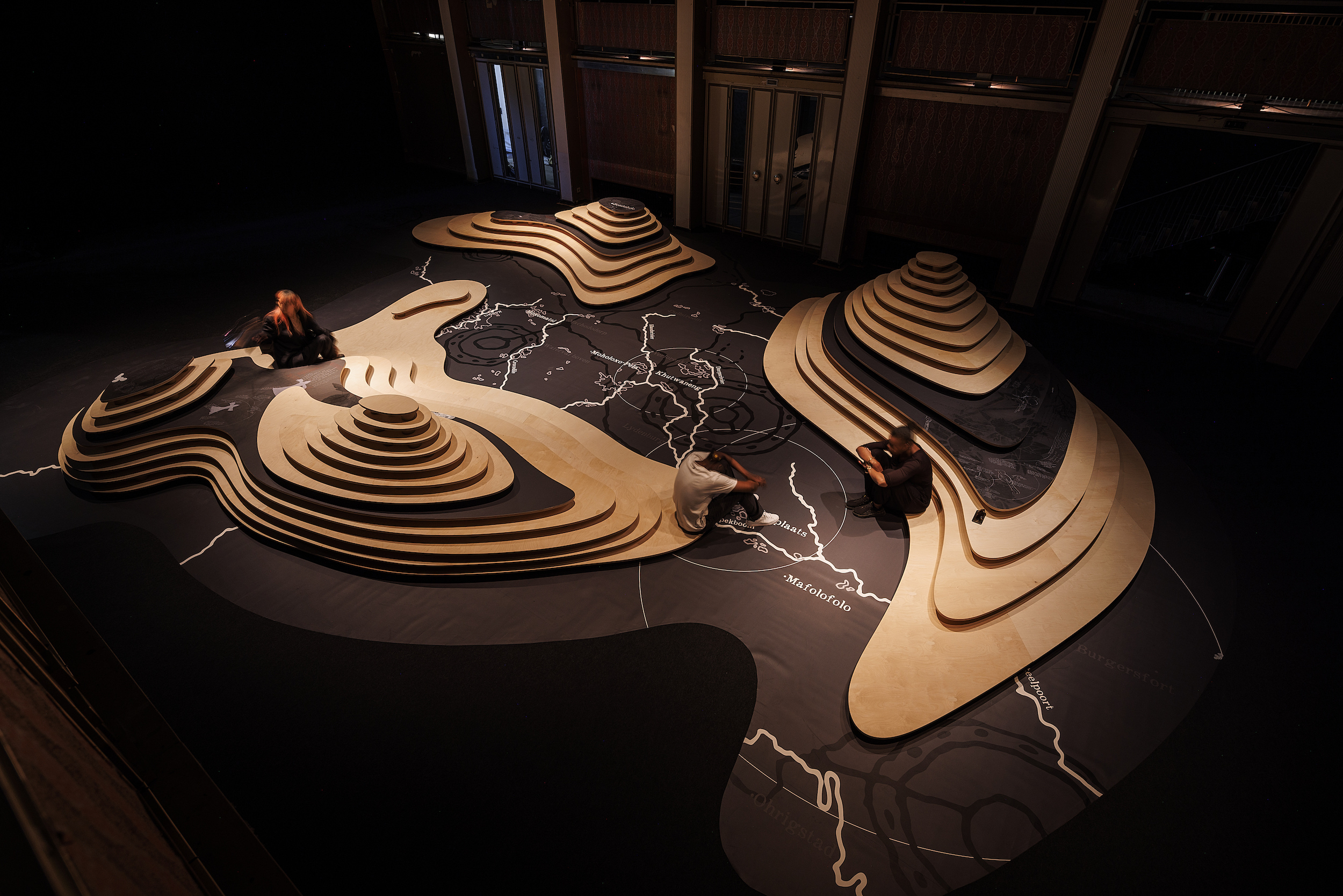

South African art collective MADEYOULOOK created an architectonic installation at Documenta 15. Photo by Frank Sperling. Courtesy Documenta

Attending Documenta is somewhat of a luxury for those based on the tip of the African continent. Particularly in light of plummeting local currencies and rising fuel costs, almost doubling the cost of flights to Europe. This event, held in the small German town of Kassel, only takes place once every five years and is deemed one of the ultimate art experiences for serious art lovers and professionals, if only to keep your finger on prevailing thinking shaping curatorial conversations. Indeed it is a ballast against the slew of art fairs and commercial events that colonise art viewing. This is the event where you expect to see well-known artists create works that are not meant for sale. As such works are large, immersive and even intangible. Attending Documenta is supposed to stretch your perceptions of art, life, and society.

However, for how long can you stretch ideas about art, without actually imploding the cult driving the appreciation of art objects and the capitalist culture that has come to define its production? Much to the art world’s dismay, Documenta 15 reportedly sets out to do so, at the behest of its artistic directors – an art collective from Indonesia, ruangrupa, with a lower-case ‘r’ (they are non-hierarchical even in textual representations). Is this the Documenta that Africans have been dreaming of – or is it a flawed scheme that further drives the divide between the so-called global-south and its more privileged northern counterparts? Are the participating artists – mostly from the global-south - simply re-performing the ideals from the '60s that the Western art world feels have slipped through their fingers? Or does the future of art reside in picking up the threads of the past and weaving a new path through the fingers of artists that are not European or American?

Some say that Documenta was headed towards a complete dematerialisation of art. Certainly, the legacy of Documenta 13 curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev culminated in a doorstopper publication with 400-odd pages of essays. Documenta 14 slid further down this ideologically driven slant, however, the rhetoric appeared to centre on ‘unlearning’. In an interview Paul B. Preciado, one of the co-curators, he suggested that Documenta 14 set out to delink “from normative ways of thinking, specialised ways of thinking, in order to be open to something that can happen that is unknown.”

At the Huebner Areal Fondation the Festival sur le Niger installed works by a range of west African artists. Photo by Maja Wirkus, courtesy Documenta

Based on accounts, images, and reports on Documenta 15, currently on in Kassel until the end of September, this edition presents a culmination of this dematerialisation-turn. In other words, there are not a lot of visual spectacles. Much of the imagery that has been filtering onto social media documenting people’s experiences at Documenta 15 tends to be of images of bean bags assembled in large circles – somewhat reminiscent of chill-out lounges at parties in the nineties. Banners with slogans and statements regarding social activism and challenging neoliberal capitalist ideology are depicted hanging nearby, presumably providing conversation starters. The sense, from afar, is that this event centres on dialogue and engagement rather than the production or enjoyment of art objects.

This might well be a natural result of Zoom functioning as the primary medium of engagement between arts professionals and even collectors during the pandemic and the desire for more face-to-face exchanges. No doubt this Documenta was assembled and negotiated via Zoom.

It is more than likely due to the novel outlook of ruangrupa and their lack of interest in imposing ideas or shaping the conversation (as had previously been the case) and in contrast, opening up for multiple conversations, not only with artists, but audiences. Apparently, children have responded very positively to this edition of Documenta.

One of the main drawbacks of commercial art events is that risk-taking is left at the door. So perhaps for whatever the failings of this Documenta, certainly the organisers took a huge risk in securing an art collective to curate it. This was done with the knowledge, of course, that they would implode expectations and traditions tied to this German exhibition-driven event.

Not only is the history of Documenta tied to single curators, with a proven record in this particular activity, but aside from Nigerian-born curator, Okwui Enwezor, they hail from Europe. In this way, appointing them as the artistic directors – rather than curators and the associations that might entail - of Documenta, there was a drive to completely ‘decentre’ this event. Not only in terms of handing over the reins to an art collective from outside the western art world but also one that would unlikely have any connections or inherent commercial interests tied to it.

Installation shot of the Wajukuu Art collective’s project at Documenta 15. photo by Nicolas Wefers. courtesy Documenta

Previous Documentas have tended to be too closely aligned to the art market. Typically, they have presented artists who have already been recognised by other western institutions and are likely to be represented by major galleries. Not always but largely. Think of Zanele Muholi – whose portraits documenting black lesbians in South Africa was a highlight of the Documenta 13. In that same edition, William Kentridge, Kader Attia, Kudzanai Chiurai and Julie Mehretu all presented large-scale works. The American critic Jerry Saltz claimed that one-third of the artists participating in that edition were represented by the Marion Goodman Gallery – not to be confused with South Africa’s Goodman Gallery. That was probably an exaggeration but the point he was making - and remains the case for other non-commercial events such as the Venice Biennale – relates to a seemingly inescapable situation where commercial interests have permeated art activities that are intended to be driven by concepts and perhaps even social issues and activism. That is, of course, if you believe that social awareness and institutional critique can’t be paired with business interests. This could be an outdated idea relating to art, particularly in economies where art industries provide jobs and are, as in South Africa, mandated to do so as part of playing a role in uplifting society.

Can the art world purify itself, or return to this ideal state where artists are more interested in the communal good instead of establishing themselves as brands via social media?

Ruangrupa appear to have been tasked with resetting the western art world, cleansing it. They have proved the perfect vehicle for decentre-ring Documenta and reconnecting with art’s historical roots – for they do so authentically – they even have the language – terms that can be applied to rejig the system and superimpose a new one derived from a non-western tradition. Lumbung is one such Indonesian term being applied as an organising principle to Documenta 15. It means communal rice barn but in this context is being applied as “an artistic and economic model (is) rooted in principles such as collectivity, communal resource sharing, and equal allocation and is embodied in all parts of the collaboration and the exhibition.”

Several commentators have suggested that Documenta 15 is redolent of the spirit and practices of the late sixties – dematerialisation of art, ideas put into practice, a return to the land, and communal living.

At the Huebner Areal Fondation the Festival sur le Niger installed works by a range of west African artists. Photo by Maja Wirkus, courtesy Documenta

“Don’t look here (Documenta 15) for what has been sanctioned by the markets and institutions. Do come to get a taste of a new attitude, one that has little interest in the materialistic pursuits of latterday society testing the hard limits of its own economic, ecological and cultural viability,” opines Andras Szanto, author of The Future of the Museum.

Are ruangrupa and the participants preaching to the converted? It would be interesting to know how many art dealers and collectors visited this year’s Documenta given the focus on less object-based practices and presenting work that is co-authored by a collective of people. The art market doesn’t value works that are co-created, though perhaps this might be happening in the NFT art market.

Instead of selecting individual artists – though they have a few of those – ruangrupa invited other art collectives or those working on projects that assist a community of artists or creatives – mostly from the global-south. Expectedly, given many such entities are operating in Africa, a fair number are from our continent. This includes the Foundation Festival from the Niger, a film production company from Uganda that empowers young filmmakers, Chimurenga, a pan-African online portal that sometimes stages live events in Cape Town, where it is based, an Algerian-based organisation preoccupied with archiving the struggle of women in their country. Another Roadmap Africa Cluster (ARAC), which is said to connect collectives in Kampala, Nyanza, Lubumbashi, Kinshasa, Maseru, Johannesburg, Lagos, and Cairo are also participating as are two other South African-based collectives called Madeyoulook and Keleketla! Library. The Nest collective from Nairobi which has staged several events at art fairs in Johannesburg was also selected to participate.

As such, the curatorial act was in putting collectivity into practice rather than just applying social awareness rhetoric to art deemed for the art market as is so often the case. In this way, specific works were not commissioned per se. There was no filtering process, or at least it seems to be the case, which, of course, backfired spectacularly. A large-scale hanging work, People’s Justice, created by Taring Padi, an Indonesia artist collective, depicting a pig-faced soldier with a Star of David wearing a helmet with the inscription "Mossad" - the name of the Israeli foreign intelligence service, caused a huge outcry as it was deemed anti-Semitic.

When the German artist Hito Steyerl announced her withdrawal from Documenta, she suggested the event did not live up to the idealistic practices at its core. She pointed to the organisers refusal for “sustained and structurally anchored inclusive debate around the exhibition, as well as the actual refusal to accept mediation.” She also referred to the bad working conditions for some of the staff, according to an article in Zeit, the German publication.

The artistic directors of Documenta 15, ruangrupa, the Indonesian art collective. Photo by Jin-Panji, courtesy Documenta

There was substantial blowback from the German government with many questioning the validity of funding such an expensive art event that had become a political liability.

“The limits of artistic freedom have been exceeded here,” urged Claudia Roth, the minister of state for culture in Germany.

The scandal sparked some interesting debates grappling with right-wing views embraced by those with a left-wing outlook.

Ultimately, can global-south entities and their work be transplanted in a western centre? Perhaps the only way to truly decentre Documenta is for it to exist outside of Germany altogether? Or to become less important or interesting for those in the global-south. We are surely not the intended audience. We can drive or walk down our streets or cities to engage with art collectives from our environs. Do we pay them as much attention as we should? Perhaps Documenta 15 will make us value those non-commercial entities that drive change at a grassroots level more.

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town based art commentator, advisor and independent researcher.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory