While Billy Monk Was Shooting

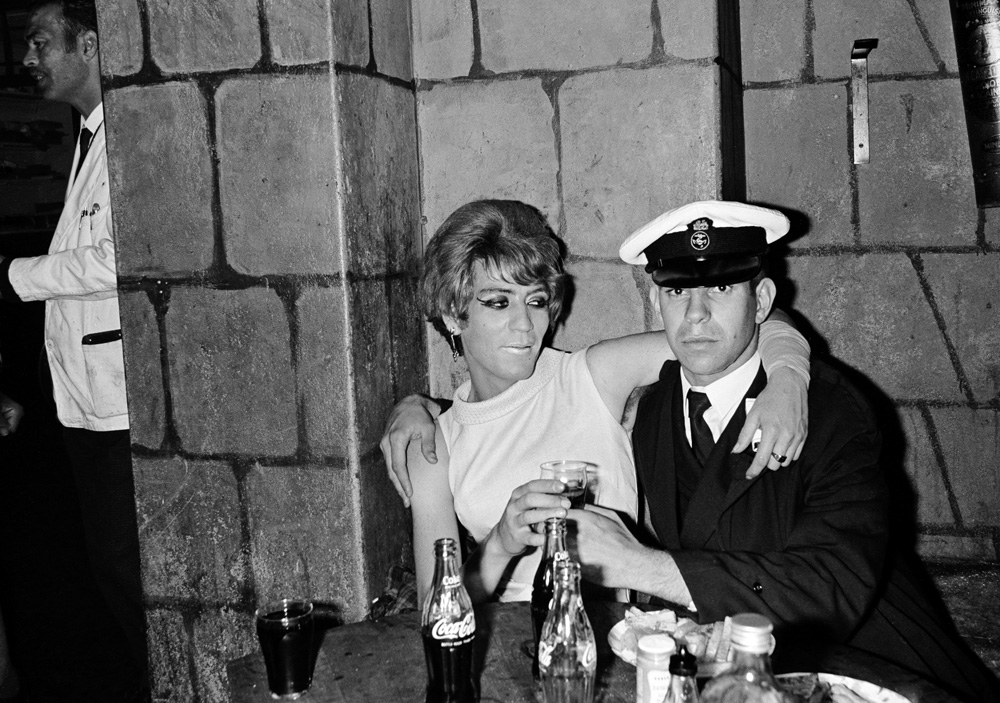

The Catacombs, August 1967

Two decades into apartheid, in the mid-1960s, in photo studios in South Africa, advertising and fashion photography saw a boom that would propel commercial photography into overdrive for the next twenty years. “Advertising agencies ruled and a handful of photographers became heroes overnight,” remembers photographer and head of the Photographic Archival & Preservation Association, Gavin Furlonger. At the same time, on the streets, press photographers were urgently documenting the terror of apartheid to share with international media that would gain momentum right into the mid-1990s and the release of Nelson Mandela. “[They] played a pivotal role in capturing the horrors that were happening on our doorsteps and sharing these images with the world press and so exposing the atrocities that were rife under nationalist rule,” Furlonger adds.

In 1967, Ernest Cole’s photo book ‘House of Bondage’ was published by Random House in New York and was banned in South Africa for revealing the inhumane conditions Black South Africans lived under during apartheid. George Hallett was documenting life in District Six before it was reclassified in 1966 according to the Group Areas Act, and between 1963 and 1968, David Goldblatt was making images for his book ‘Some Afrikaners Photographed’ which would only be published in 1975.

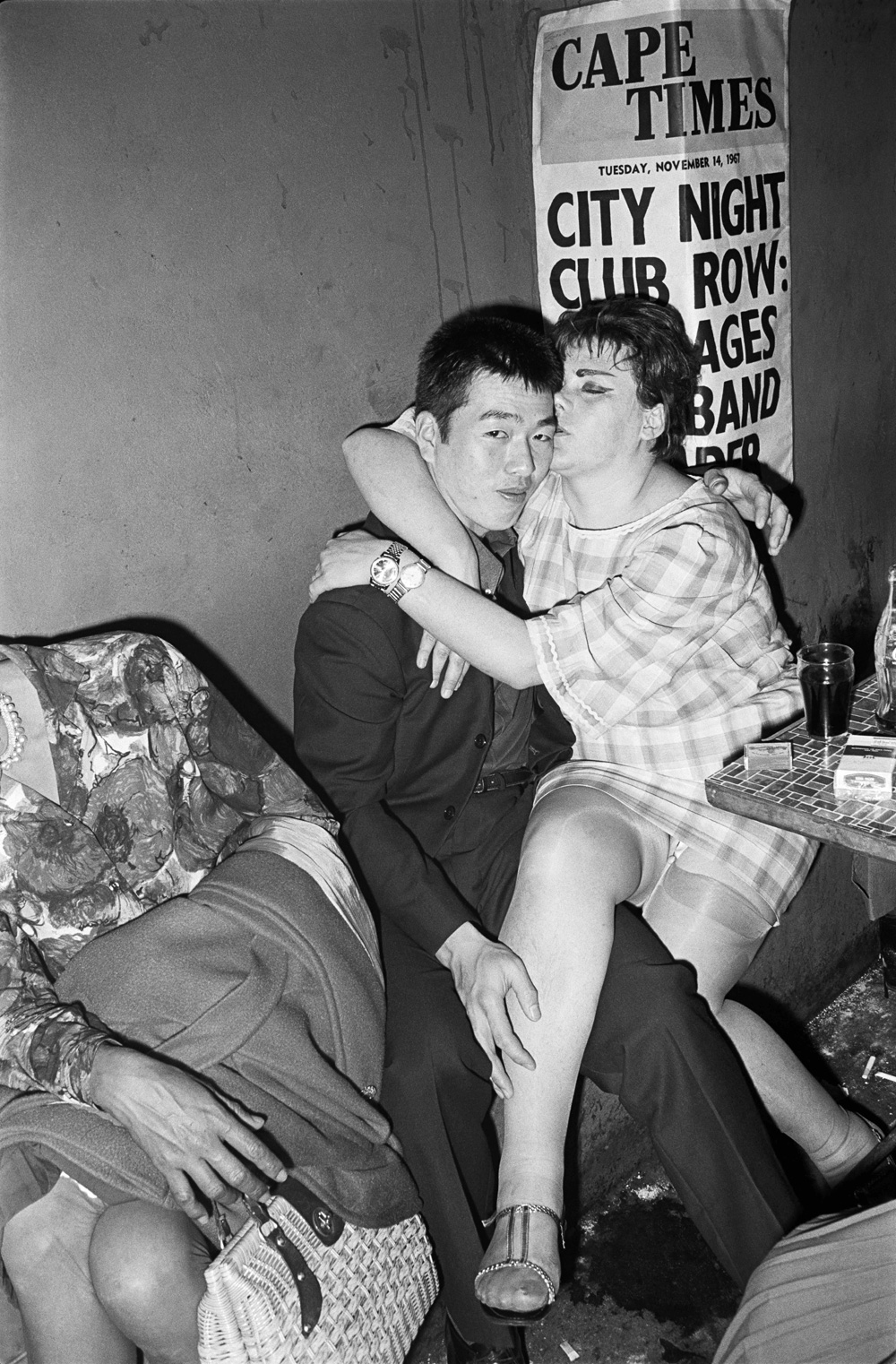

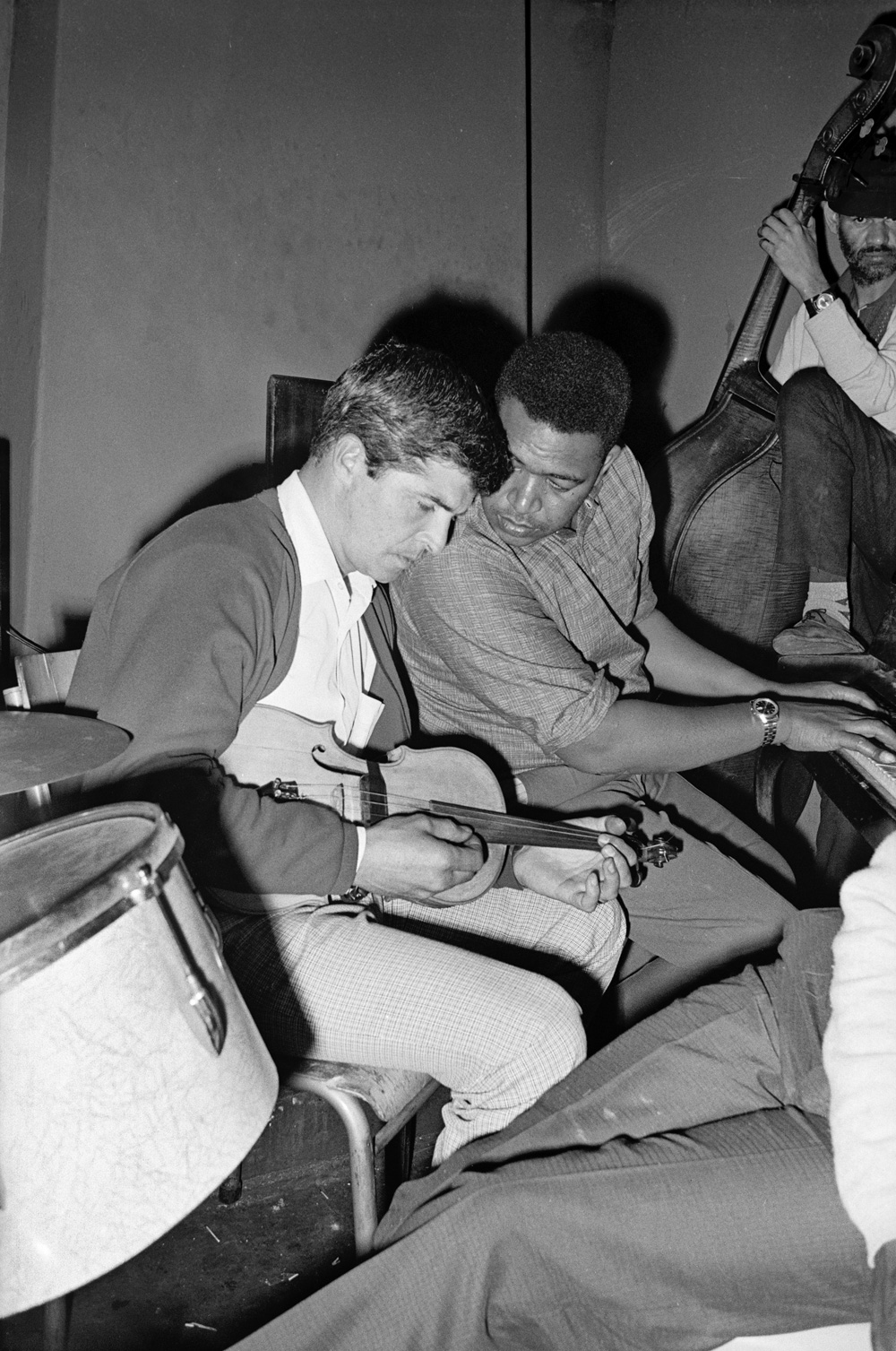

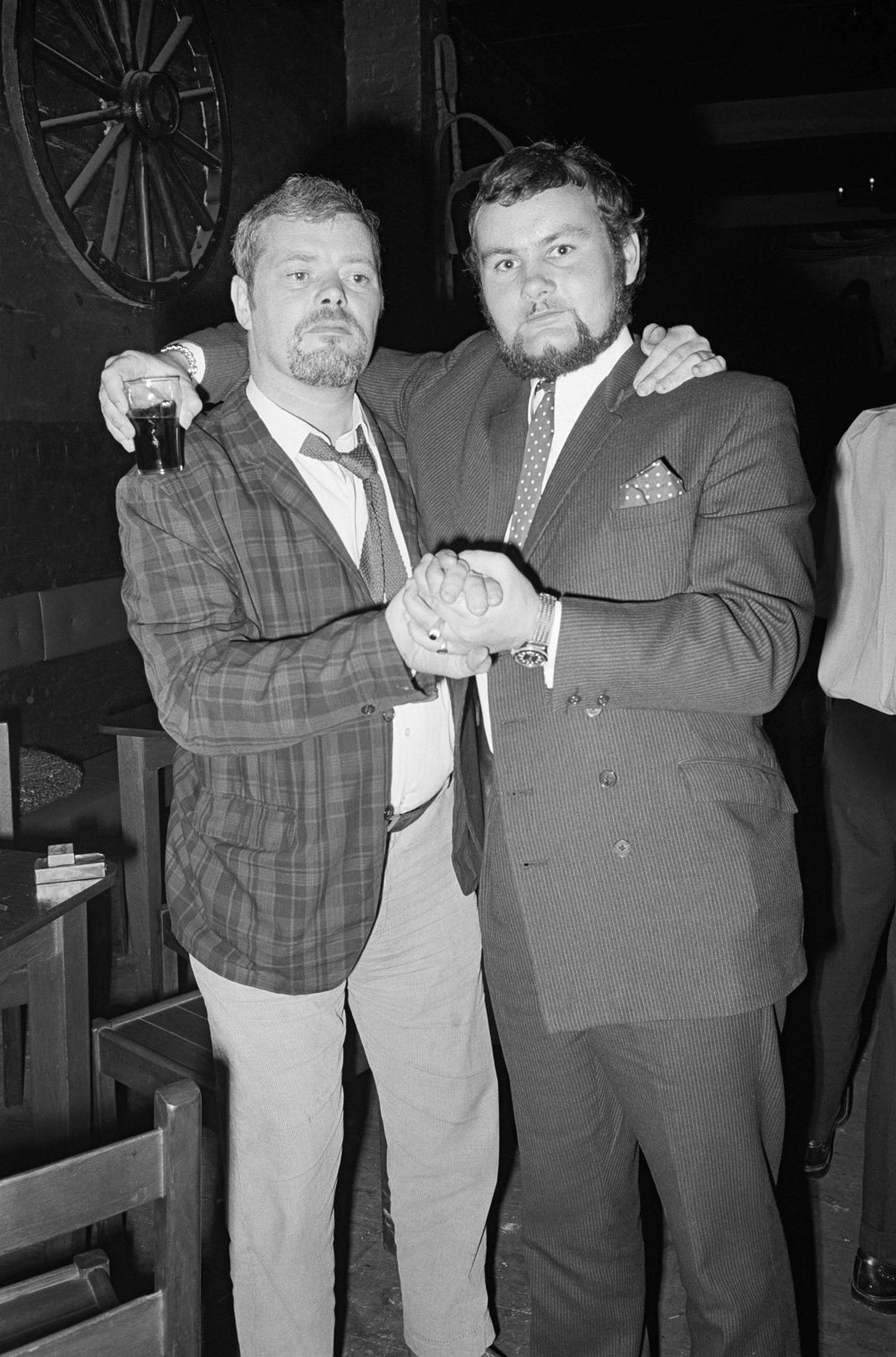

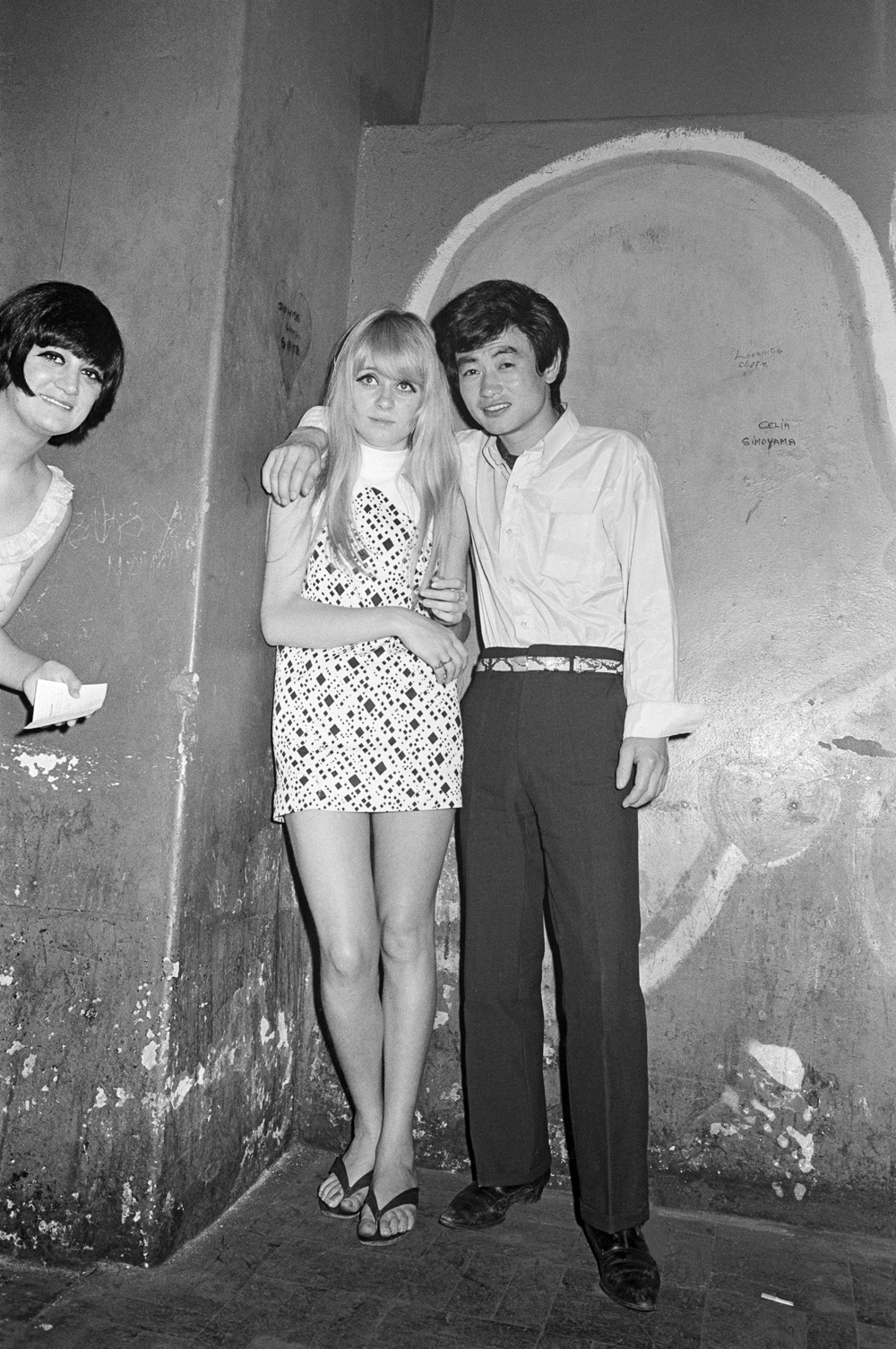

Meanwhile after dark in a dockside nightclub in Cape Town called the Catacombs, a man named Billy Monk was concerned with neither slick commercial photography, nor taking photographs that would make world news. He was making a quick buck. Despite the laws of the time, revellers of different race and class would mix and mingle all night in these underground clubs; east Asian sailors, local sex workers or ‘sugar girls’, coloured jazz musicians, artists, LGBTQ people, and white southern suburbs teens seeking thrills.

The Catacombs, 23 December 1967

The Catacombs, 1 December 1967

The Catacombs, 20 October 1967

From 1967 to 1969, Monk was a bouncer at the Catacombs and to make extra money he would take happy snaps of the club-goers and sell the prints back to them the following night. But among his party pics were photographs that showed an excellent eye and sharper instincts. He had ambitions to become a well-known photographer, and as an insider in this underworld, his familiarity with his subjects allowed him and his Pentax rare access and authenticity. His subjects weren’t activists but through their nightly crawls and brandy brawls, theirs was a joyous jazz- and booze-fuelled rebellion against the oppression of the day.

The party was over by the end of the decade. Containerisation changed the way the shipping industry worked and with that the dockside nightlife dried up. In 1966 the previously mixed, nearby neighbourhood of District Six was declared a whites-only area under the Group Areas Act of 1950 and from 1968, non-white inhabitants were forcibly removed to the Cape Flats 25 kilometres away. Monk drifted on to the west coast in search of a more lucrative career diving for alluvial diamonds. He left behind a collection of meticulously labelled negatives with studio mate and photographer Paul Gordon. Perhaps he knew the value of what he had captured, which is now critically acclaimed.

Photographer Jac De Villiers took over Gordon's photo studio. In 1979, he and journalist Lin Sampson were tidying up the space when they rediscovered the box of Monk's negatives and went through its contents. They were impressed by Monk's work that had been lying in a corner of the studio for almost a decade. With Monk’s blessing De Villiers staged an exhibition curated by David Goldblatt at The Market Gallery in Johannesburg in 1982. On the way to view his own exhibition, Monk made a pit-stop in Cape Town where he was shot dead in a drunken argument. He would never see his work published.

Outside the Catacombs, 21 December 1968

The Spurs, 27 February 1968

There are many reasons why Monk’s photographs weren’t published in the sixties. “Although Monk had ambitions to be taken seriously as a photographer, the content of his work depicted so many aspects that were illegal in South Africa at the time – mixing of races, unlicensed alcohol and homosexuality,” says Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, archivist for the Billy Monk Collection and director of ‘Billy Monk – Shot in the Dark’.

“There would not have been any publication, or tabloid, that would have dared to publish photographs so revealing such as the likes of Billy Monk's nocturnal meanderings around Cape Town's ‘club' circuit,” Furlonger adds.

Billy Monk was included in the 2012-2013 exhibition ‘Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life.’ alongside Hallett and Cole. Co-curator, Dr Rory Bester says, “It was only really in the late 1970s going into the 1980s that you find a lot of alternative publications emerging that would’ve been able to give voice to something like Billy Monk’s project.”

According to Bester, it’s unlikely though, that Monk’s work would have been banned like Cole’s. “Obviously very political photographs were banned,” he says. “but the apartheid state wasn’t especially interested in visual art. It was political figures who were banned, it was writers who were banned.” However there were cases like that of resistance artist Gavin Jantjes who was forced into exile and whose project ‘South African Colouring Book’ — a series of silkscreens which used Cole’s and Hallett’s photography — was banned in South Africa. “Billy Monk’s images weren’t actually shown at the time so we have no real sense of how they might’ve been received,” Bester says.

Although in 1966 prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd was assassinated — a major blow to Afrikaner nationalism — Bester says that in the late 1960s, to a large extent, the apartheid state felt invincible. “Most of the leaders of the ANC were in jail, the country had seceded from The Commonwealth, it was independent, it was before the start of the Angolan war. So I don’t know if the state was that concerned with photography.”

But, as Furlonger says, “Billy was just a bouncer with a camera.” He wasn’t a big name in photography who might have been exhibited in shows organised by the ‘Camera Clubs’ of the time. And the art world in South Africa didn’t recognise or value documentary photography as it does today. Furlonger organised the first ever exhibition of South African photography at the Iziko National Gallery only in 1980. “[In the sixties] photography wasn’t considered something you put in galleries and you bought and invested in as an artistic category,” Bester says. “Photography was something that appeared in magazines and newspapers as fashion and news. Art photographers and documentary photographers had to be doing other things as day jobs in order to survive. Goldblatt at that time wasn’t making money out of the photography that we now associate with him, he was making money out of magazine work.”

Perhaps it’s necessary for time to have passed to realise the value of Monk’s images of this slice of subculture in South Africa’s broader history. There’s a particular impact the images have now looking back, and will have for future generations learning about apartheid in classrooms. The freedom and debauchery in Monk’s images wouldn’t be associated with apartheid-era South Africa. If one looks at apartheid legislation, Monk’s world seems impossible. “But I think in reality there was a lot more mess in terms of the social orchestration of apartheid,” Bester says.

The Catacombs, 29 October 1967

The Catacombs, 1968

Cameron-Mackintosh first became aware of Monk’s work when he moved to Cape Town in 2007. “Billy Monk carried a certain mythical status where his story and photography resurfaced every few years in publications and exhibitions,” he says. But it was almost a decade later that he learned a selection of Monk’s images were on display at Furlonger’s Gallery F in Cape Town. “A visit to Gallery F confirmed what I had hoped – that the archive was more extensive than the 50 published photographs in circulation. I learned Gavin was not only the custodian of the archive but acting guardian to Monk’s two children.”

Together Furlonger and Cameron-Mackintosh founded the Billy Monk Collection in 2017 to preserve Monk’s legacy and to ensure that his photographs continue to be appreciated. “The collection is not only aesthetically appealing,” Cameron-Mackintosh says, “but an important document of this part of South Africa's and particular Cape Town's history and this unique subculture that many Capetonians are not even aware of.”

“Whether he was photographing drunken sailors, local ‘sugar girls’ or suburban ladies roughing it for the night, Monk managed to capture sweet, fleeting glances and glimpses of humanity in trying times.”

The Spurs, 11 October 1968

UNSEEN is a collection of ten never-before-seen portraits by Billy Monk available exclusively on Latitudes from 15 - 18 July 2021.

Custodians of the Billy Monk Collection, Gavin Furlonger, and Craig Cameron-Mackintosh will give an online talk, at 6 PM SAST on 14 July, to talk about Billy Monk and the new UNSEEN selection. We would love you to join us for this talk, which will be facilitated by renowned arts journalist, Sean O'Toole. Click here to register.

Written by Alix-Rose Cowie

Special thanks to Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, Gavin Furlonger and Dr Rory Bester.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory