When art collections go public

Some African based collectors seem more interested in advancing art than their own taste, when they bring their works into the public realm. Others want to drum up the value and interest in the artists they support.

----------------------------

Alexis Preller, The Red Pineapples, oil on canvas board was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

Alexis Preller, The Red Pineapples, oil on canvas board was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

There comes a point, particularly with large or focused art collections, that their owners feel compelled to share the works with the wider public. This can be done through loans to museum shows, inviting curators to engage with it, or, in some instances, creating a private museum for it. Art is created to be seen after all and no one likes the idea of art sitting in storage. The more an artwork circulates, particularly in exhibitions the more likely its value will increase, or at least its pedigree and the overall status of the art collection. Attracting status to a collection has all sorts of benefits, not only will the sale of the works of it at auction have a better chance of fetching high estimates (or selling), but the collector might also in the process accrue some bargaining power with dealers and artists, who might be incentivised to offer healthy discounts or give them first dibs on sought after works. Ideally, dealers and artists prefer works to go to high-profile collectors or museums.

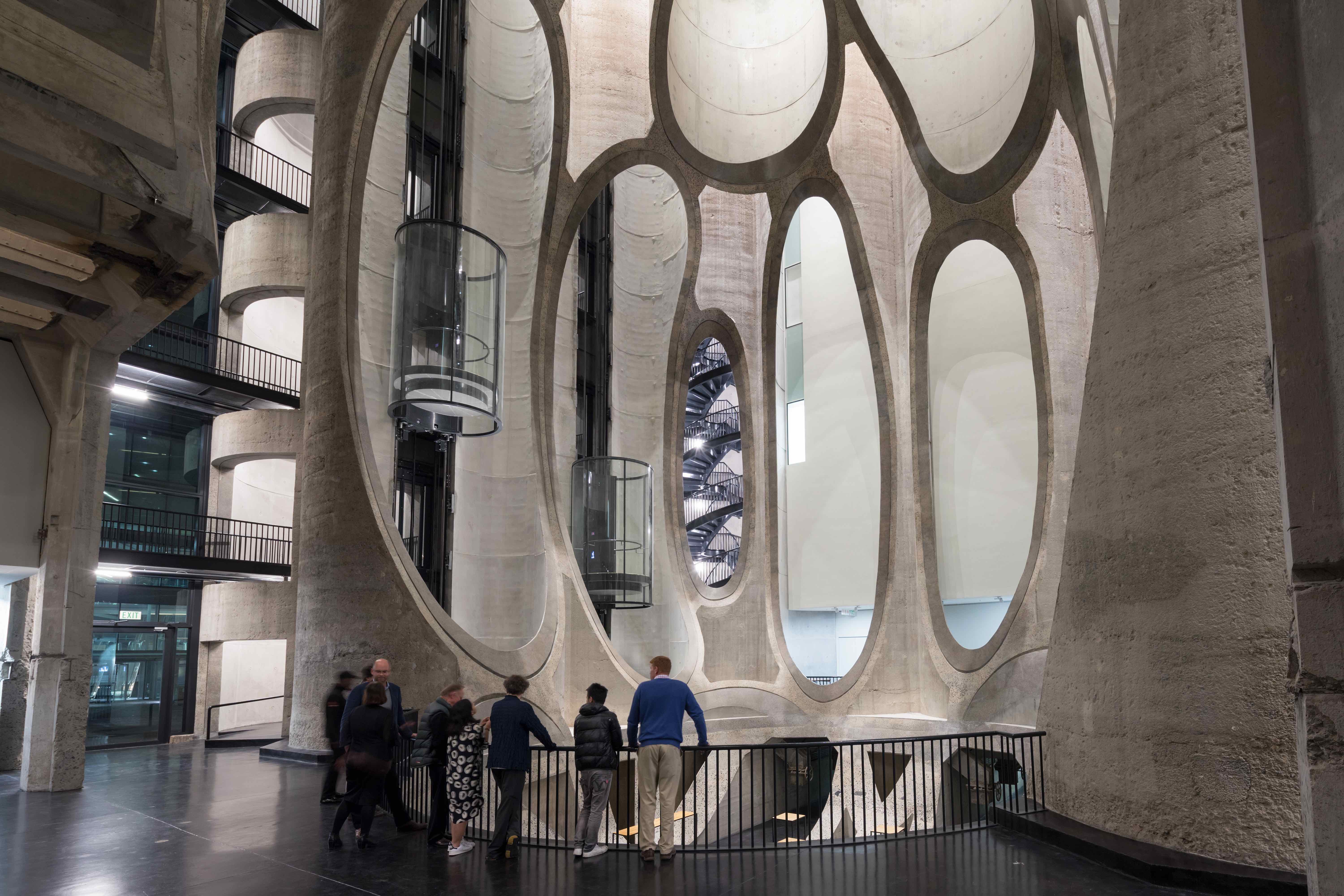

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, bears the name of the German collector Jochen Zeitz. However, the museum itself is a private/public partnership where only a few works from his collection are shared with the public at this venue. Largely, works are loaned for exhibitions.

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, bears the name of the German collector Jochen Zeitz. However, the museum itself is a private/public partnership where only a few works from his collection are shared with the public at this venue. Largely, works are loaned for exhibitions.

While some high-profile collectors of African art opt to create buildings for their works and that of others, some are choosing to exploit technology by sharing and supporting the artists in their collections, through websites, Instagram accounts, and newsletters, where they might announce their new acquisitions or artists they have just “discovered”.

There are estimated to be around 400 private museums in the world, according to Georgina Adam in The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum (2021). They are however expensive to build and maintain and there are costs in keeping them ‘relevant’ and useful to society, through programming and audience development. In South Africa, there are at least six private art museums or foundations.

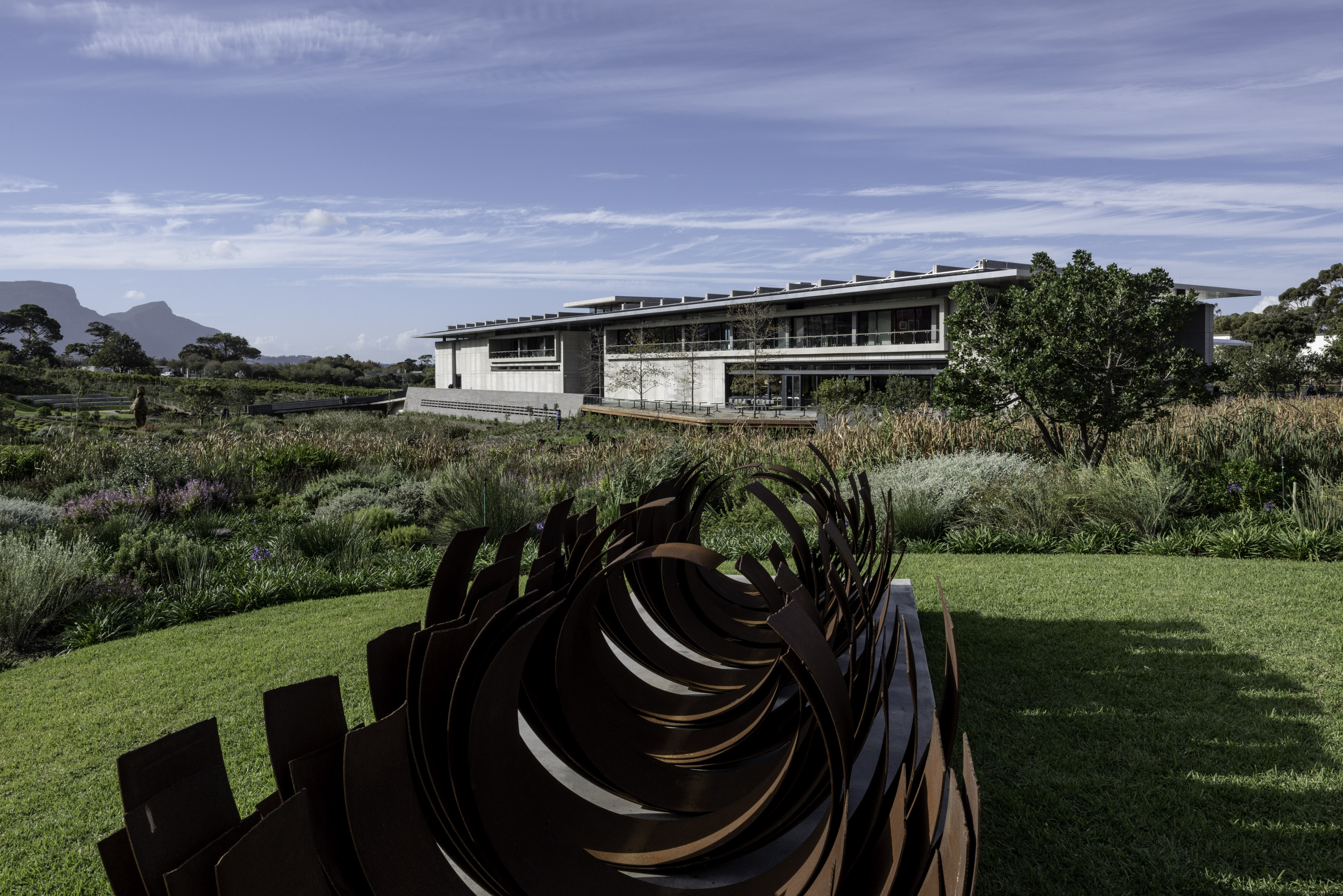

Interestingly, some of the private museums that have been established in this country haven’t necessarily been driven by a need to make a large contemporary collection available to the public due to a focus on historical works. The Javett Art Centre and the Norval Foundation are probably good examples of this, or at least we imagine this to be the case given their programming – Javett’s inaugural exhibition 101 Collecting Conversations: Signature Works of a Century relied on institutions loaning their eponymous signature works. An assumed (their collections are under lock and key) paucity of contemporary African works in these collections has been beneficial in the sense that the collectors behind these private and private/public partnership museums – The Javett family and Louis Norval and his family – have in a sense gifted an institution to the public rather than simply a collection. The drive to loan contemporary works has made for more interesting exhibitions and dialogues.

The establishment of private art museums in South Africa, such as the Norval Foundation, is not only to do with collectors sharing their works, but to provide a space for dialogue between collections and works. Photography by Wieland Gleich

The Johannesburg Contemporary Art Foundation should on paper be drawing from three collections as it is funded by three prominent art collectors Gordon Schachat, former deputy chairman and co-founder of African Bank Investments Ltd; Adi Enthoven, the chair and non-executive director of Hollard and executive chairman of private investment group Yellowwoods; and the former group president and CEO of MTN, Phuthuma Nhleko. These wealthy patrons all have considerable art collections and the Southern Collection, of which the Enthoven and Schachat families are also partners is also said to be one of the most comprehensive contemporary art collections in the country. However, at this modest private art museum - compared to the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, the Javett or the Norval in terms of its dimensions - its programming, under the curatorship of Clive Kellner, also relies on loans from other collections. This is largely due to a focus on connecting South African contemporary art to that produced in the global south.

In this way, the focus of these museums is not to simply parade the collectors’ taste in art but to stage meaningful conversations with some of their works. In the process, they are also providing much-needed opportunities for curators and new platforms for African art to be valued and validated and are increasing access to art.

Some other well-known South African collectors such as Jack Ginsburg or Emile Stipp, a chief actuary at Discovery Health, have carved out collections largely focused on a particular medium. Ginsburg is renowned for his love for art books – that is artworks that resemble physical books or cunningly exploit this format. Works from this idiosyncratic collection are regularly displayed in a dedicated space at the Wits Art Museum. Stipp has a broad collection of artworks but decided to focus on collecting video works, which have been undervalued.

Stanley Pinker, The Bathers , oil on canvas was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

Stanley Pinker, The Bathers , oil on canvas was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

“Video art is so much easier to share, all you need is a room and a projector.”

The pleasure of owning art is in sharing it, observed Stipp.

“Art only has meaning when you share it and communicate what it is about,” he said.

Some important collections only come into public view after their owners have deceased and they come up at auction. Such was the case with the highly publicised auction of the Nwabisa Xayiya's collection at Aspire Art Auctions. The Joburg socialite was still a young woman when cancer tragically took her life, but in her short lifespan, she had managed to acquire over 300 significant works with her husband Mikki Xayiya. A dedicated sale of a collection such as this not only resulted in a well-attended exhibition, the production of a researched catalogue, but also dispelled notions that young black collectors aren’t interested in historical works by white artists such as Pierneef.

“Artists, artistic production, and the whole art-industry needs collectors and benefactors. It is crucial for the sustainability of the industry that we develop and cultivate ambassadors who see and feel the value of what art does for cultures and communities. Nwabisa was remarkable in this regard and I think she was a strong influence on many of her contemporaries, and a younger generation of burgeoning collectors, to start collecting. I believe we need more Nwabisa’s in our society,” says Ruarc Peffers, Senior Specialist, Managing Director Aspire Art Auctions house.

Other significant, large collections of African art beyond Africa’s borders are shared via regular newsletters by the collectors. The French-owned Leridon collection (owned by Gervanne and Matthias Leridon) and the Israel-based Africa First collection established by Serge Tiroche are good examples of this approach. Their collections parade an independent identity from their owners – they have their own logos and websites, and conduct residency and other programming which supports artists whose works are in their collections.

JCAF: The Johannesburg Contemporary Art Foundation was funded by three well-known art collectors, however, like other private art institutions in South Africa the emphasis is on loaning works from other collections to expand on knowledge about art. Photography by Graham de Lacy

JCAF: The Johannesburg Contemporary Art Foundation was funded by three well-known art collectors, however, like other private art institutions in South Africa the emphasis is on loaning works from other collections to expand on knowledge about art. Photography by Graham de Lacy

What is particularly striking about both of these collections is the fact that the only binding narrative appears to be that the works are made by African artists. In this way, they almost view African art as a ‘thematic’ – despite its broadness and diversity. The Leridons appear to view supporting African art as a philanthropic cause, whereas Tiroche appears more committed to driving up its value – through his association with auction houses, curating sales of it in the US such as Philips and using his Instagram account to document the prices works from his collection fetch on auction. In both instances, these collectors are playing an active role in not only supporting artists – through residencies and other programmes, but in encouraging those in their native countries and art markets in the US and Europe to pay more attention to art from our continent. Championing African art is admirable, though some might view this as paternalistic, or self-aggrandising. Yet the capital and promotion that has gone into the Leridon and Africa First collections have been so consistent and substantial that they have secured their importance and value to the African art market.

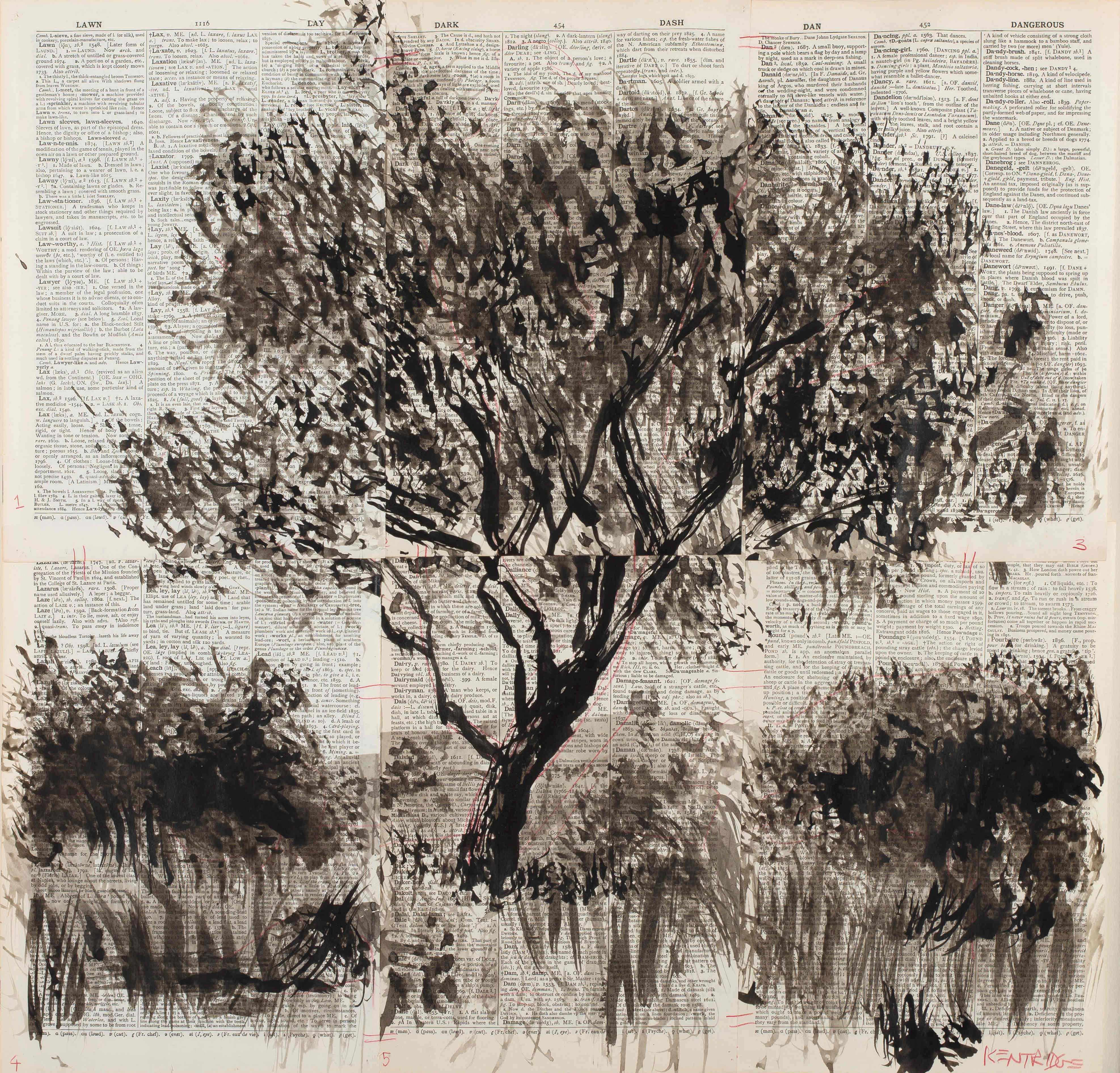

William Kentridge, Tree, was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

William Kentridge, Tree, was part of the Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Estate. It was auctioned by Strauss & Co.

A museum, of course, solidifies this role in perpetuity. This may be why Jean Pigozzi, a well-known collector of African contemporary art, has recently announced he will build a museum in Cannes to house his collection. He has been collecting African art for 20 years now and has accumulated over 10 000 pieces, though he recently admitted in an interview with Artnet that only 2000 of them are significant. He too, as with other collectors, seems to view the African origin of the artist as the defining criteria for his collection, though perhaps there are some focused collections of works in it. The French-born entrepreneur wishes for his collection to be “recognised as the best African art collection.”

Hopefully, a host of ambitious African-based collectors won’t leave it to the French to define what that appellation might entail.

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town-based commentator, advisor and independent researcher

The establishment of private art museums in South Africa, such as the Norval Foundation, is not only to do with collectors sharing their works, but to provide a space for dialogue between collections and works. Photography by Wieland Gleich

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory