What do we do with misogynist male artists?

Does the Brooklyn Museum’s Pablo-matic show plot a good way forward?

---------------

- By Mary Corrigall

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

The foundations of Western art history are currently undergoing a profound reevaluation, spurred by a growing recognition of the contributions made by women artists who were often marginalised or overlooked. One such artist is Hilma Af Klint, whose abstract vocabulary predates the male artists traditionally credited with advancing modernism. Inserting female artists into this narrative has been met with some resistance - recently from male critics who appear to be less than enamoured by Hannah Gadsby's cheeky show on Picasso currently showing at the Brooklyn Museum in the US.

The exhibition was timed to coincide with the 50 year anniversary of the famous Spanish artist’s death and its wry title, It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby, clearly staked it out as one intended to draw attention to the titular ‘problematic’ aspects of Picasso’s work – and life. It has generated more attention than the numerous other shows held in museums to commemorate Picasso's anniversary, including one curated by fashion designer Paul Smith at the Musee de Picasso in Paris, which features an installation by Mickalene Thomas, a queer artist also represented in the Brooklyn exhibition.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Reclining Nude, April 1932. Oil on canvas, 51.2 × 63.6 in. (130 × 161.7 cm). Musée national Picasso/Paris/France; MP142. © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Photo: Adrien Didierjean, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York)

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Reclining Nude, April 1932. Oil on canvas, 51.2 × 63.6 in. (130 × 161.7 cm). Musée national Picasso/Paris/France; MP142. © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Photo: Adrien Didierjean, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York)

Ultimately, this is because, apart from being curated by a comedian, it digs into one of the cultural conundrums of our time – can we separate abusive or misogynist men from their art? In the African art context, where we are still in the process of canonising male artists, we seem to be much quicker to 'cancel' living artists - though under pressure.

Observers in the global South, who have long recognised Picasso's debt to African art and advocated for an alternative narrative of modernism, may find it perplexing that only now are his well-known problematic aspects being addressed in a museum show. However, there are many renowned artists and figures in the South African art scene whose abusive behaviour or gender-bias have largely been ignored or swept under the carpet until it was impossible to do so and female curators have struggled to include them in exhibitions in a way that wouldn’t cause an uproar.

A striking example is the case of Zwelethu Mthethwa, an artist found guilty of the murder of Nokuphila Kumalo, a sex worker. During and after his trial his works were included in exhibitions - Our Lady at Iziko SA National Art Museum and All in a Day’s Eye: The Politics of Innocence at the Javett ARtTCentre. In both instances there was a public uproar. Many stories about the artist's behaviour came out the woodwork after the trial.

This is perhaps an extreme example. Perhaps a closer local comparison might ironically be with a female artist such as Irma Stern, whose portraits of people of colour remain problematic yet this aspect of her work has never been dealt with head-on in a prominent exhibition, though artists - such as Athi-Patra Ruga - have been invited by the Irma Stern Museum to engage with this issue. Can you have your cake and eat it - show the work while rejecting aspects of it that don't align with the current social outlook?

Does the high value of an artist’s work or their status compel greater silence? Picasso did not commit murder and he has been dead for half a century. However, the recent death of Francois Gilot, famously the only woman “who said no” to Picasso and walked out on him has highlighted not only the artist’s toxic behaviour towards Gilot – he destroyed all her possessions, art and her career as an artist in France (according to Sascha Llewellyn in an article in The Guardian) but the complicity of an establishment. Strikingly, French museums do not possess a single work by Gilot in their collections, despite her prolific career as an artist and her significant influence on Picasso's ceramic art. When Gilot published a book on Picasso, it faced calls for banning from 80 prominent intellectuals and artists, revealing the extent of the institutional complicity. However, such complicity would be unimaginable in today's climate.

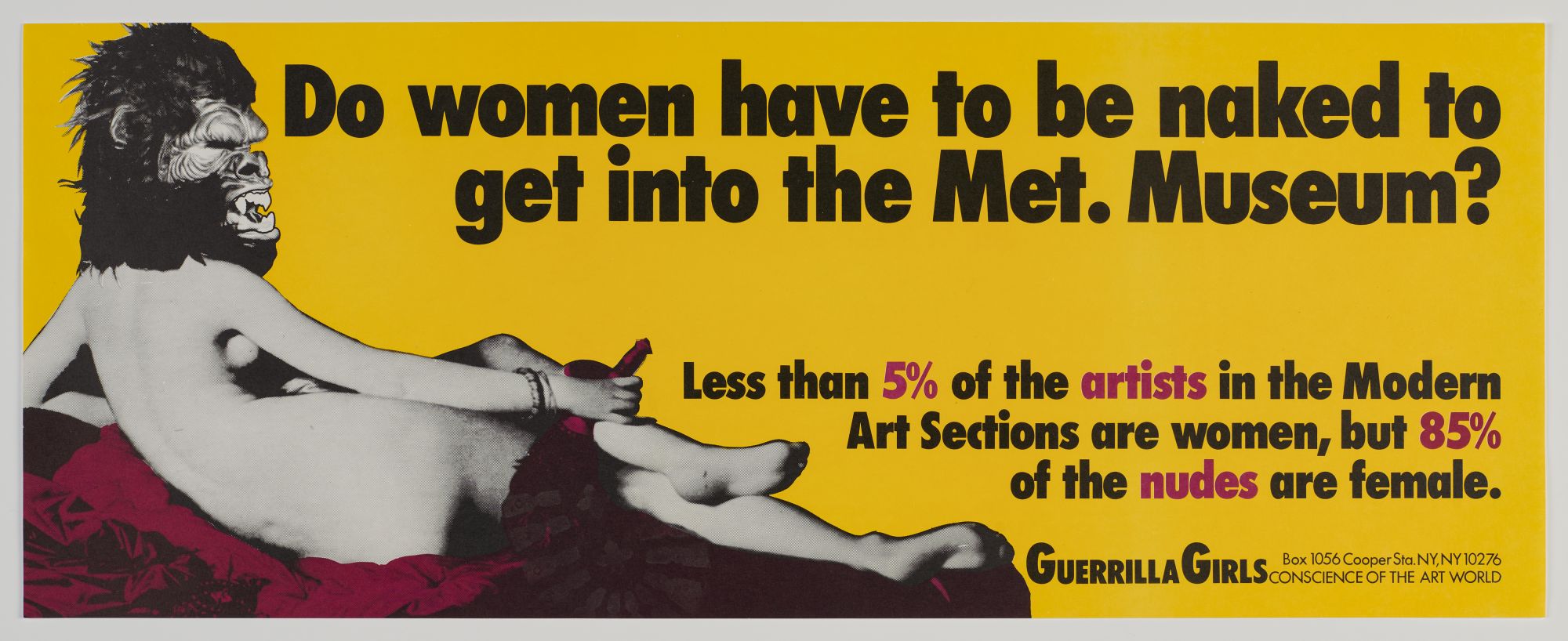

Guerrilla Girls (established United States, 1985). Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum?, 1989. Offset lithograph, 11 × 28 in. (27.9 × 71.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, Inc., 2017.26.54. © Guerrilla Girls. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Guerrilla Girls (established United States, 1985). Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum?, 1989. Offset lithograph, 11 × 28 in. (27.9 × 71.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, Inc., 2017.26.54. © Guerrilla Girls. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

When it was reported that South African artist Mohau Modisakeng had been abusing his female partner at an airport in Jomo Kenyatta Airport in Nairobi, Kenya in 2018, women who witnessed the event took to social media, sharing the incident and condemning Modisakeng's actions. Writer and public intellectual, M Neelika Jayawardane, who was due to speak at the opening of an exhibition, Continental Drift: Black / Blak Art from South Africa and north Australia, that included Modisakeng’s work was conflicted about what to do. The curators of that show were not aware of reports surrounding Modisakeng and told Jayawardane that “when there were allegations of unethical or violent behaviour against an artist, her institution had waited for a court of law to charge the person before making decisions about removing their work or making any public statements.”

In an open letter by Jayawardane published on Al Jazeera, she disagrees with this approach, implying that this kind of inaction or silence inadvertently, supports “a culture of silencing and the myth that violent “complicated” men produce brilliant work and that if abusers were no longer accepted we would have empty spaces or mediocre work on our walls.”

Are institutions more severe on black artists as opposed to white ‘masters’? Given Modisakeng did not represent women in his works – they mostly centred on images of himself – would it be easier – sometime in the future – to separate his art from his alleged behaviour? Or do images of him holding weapons hint at a darker reality given what was reported in the press – or do we wait for a tell-all book or judge to make a pronouncement?

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

Criticism of Gadsby's exhibition has primarily come from male art critics who resist the idea of shining a light on Picasso's misogynistic tendencies Is he simply too big a character in art history to be undermined, and perhaps there is a fear that this pervasive feminist revisionist curatorial eye could reach into the crevices of every museum’s art collection – or worse, destabilise the monetary value of works by the ‘masters’ at the high end of the art market? Or is it Gadsby, their (their chosen pronoun) seemingly crude take-down of this modernist master that has ruffled feathers?

In considering this debate, it is important to note – as with many of the #MeToo revelations and cases - that this revisionist approach of Picasso’s oeuvre is being driven by women. Gadsby may have been the public face of the Pablomatic but it was co-curated by Catherine Morris – head of the Center (sic) for Feminist Art at Brooklyn Museum and Lisa Small, a senior curator of contemporary art. In an interview with the Art Newspaper, they suggested that it was another woman who instigated the exhibition - Cécile Debray, President of the National Picasso-Paris Museum, who approached the two curators at the Brooklyn Museum and invited them to stage a show that reconsidered Picasso’s legacy. Gadsby came to mind, as they had made headlines for railing against this master of modernism during their hit Netfilix show Nanette, where Gadsby opined that, “Picasso’s affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter has become just another part of his oversized mythology as a tortured, insatiable artist. He once said that he wanted to burn all women when he was done with them, destroying them so that he no longer had ties to the past.”

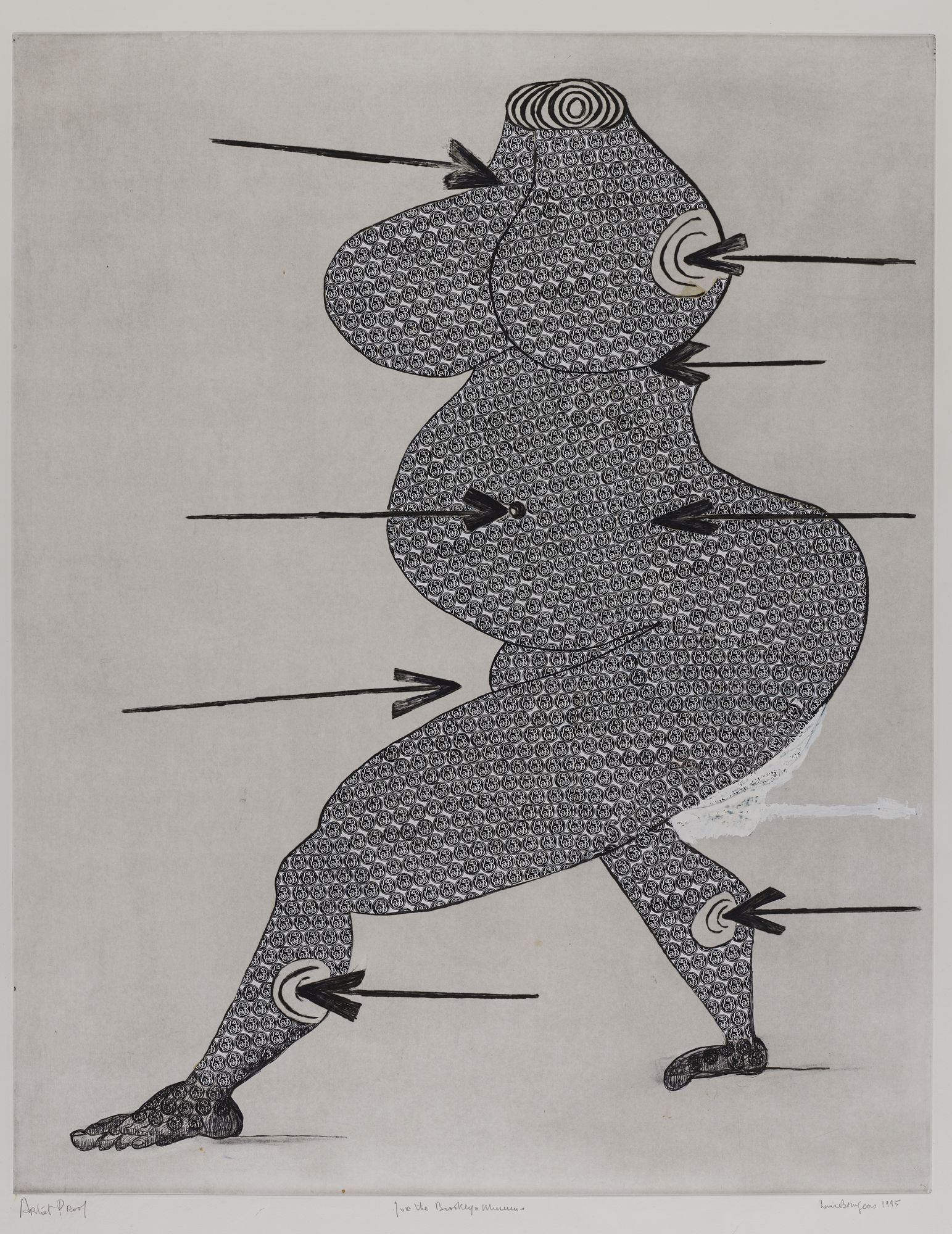

Louise Bourgeois (French American, 1911–2010). Tapestry, trial proof, 1995. Drypoint, etching on paper, 47 3/8 × 37 in. (120.3 × 94 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Gift of the artist, 1995.33.2. © 2023 The Easton Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

It makes sense that Debray would approach the Brooklyn Museum – they are the only museum in the US – or perhaps elsewhere that has a centre dedicated to Feminist Art – and as they serve the largely African-American community in that part of New York there has for some time been what you might term a ‘decolonising’ agenda driving some of their programming. This is the museum where African art and artists often find an institutional foothold in the US – currently the Africa Fashion exhibition is showing here.

In this way, Debray, deliberately invited a critical exhibition examining Picasso’s legacy. More than likely she did so not only because she is a woman well aware of his chequered history with women not only in his personal life but in the way he objectified them in his art, but to ironically keep Picasso relevant in such a way that aligned with the times and made him interesting to people outside the art world. This is where Gadbsy came in, and Paul Smith, the British designer, who was also invited to curate a show on Picasso’s work at the Picasso Museum, Paris.

Perhaps Debray figured that the French would perhaps be less open to a feminist revisionist approach and what better way of sidestepping Picasso’s less noble aspects than a show that focussed on the more formal qualities of his art such as colour, line, texture, which Smith would bring to the fore.

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

Installation views, It’s Pablo-matic/ Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby. Brooklyn Museum, June 2-September 24, 2023. (Photo/ Danny Perez)

Smith is less qualified than Gadsby – who studied art history – to curate an art exhibition, yet his exhibition has not been so thoroughly rejected by the art critics, though Ben Luke suggests in his review in the Art Newspaper that Smith’s interventions are ‘catastrophic.’

Much of the criticism aimed at Pablo-matic could superficially (without seeing either of the shows) be applied to Smith’s exhibition, Picasso Celebration: the Collection in a New Light, which also included numerous works by female artists and displays that do not directly reference specific Picasso works.

In his Art News review of the exhibition Alex Greenberger claimed to be greatly bothered by “the show’s disregard for art history, the discipline that Gadsby studied, practiced, and abandoned after becoming frustrated with its patriarchal roots.”

Greenberger unwittingly touches on the irony of his critique. How is it possible for female or non-binary curators to show ‘regard’ for a history of art that has excluded womxn? A revisionist approach demands that curators eschew art history and steer a parallel path, which Gadsby, Small and Morris achieved by simply including many works by female artists – some of whom were active while Picasso making art - such as Käthe Kollwitz.

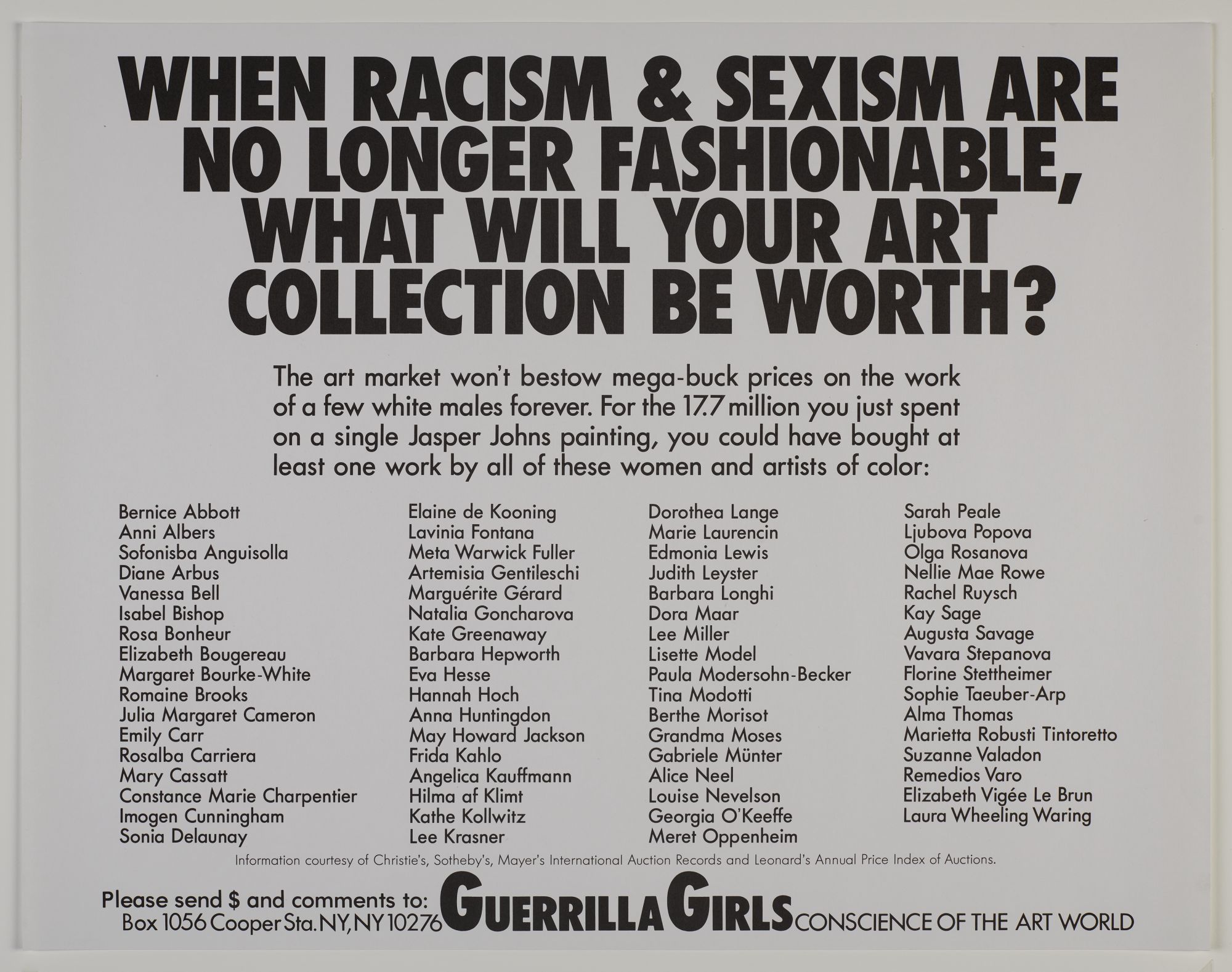

Guerrilla Girls (established United States, 1985). When Racism and Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, How Much Will Your Art Collection Be Worth?, 1989. Offset lithograph, 17 × 22 in. (43.2 × 55.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, Inc., 2017.26.24. © Guerrilla Girls. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Guerrilla Girls (established United States, 1985). When Racism and Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, How Much Will Your Art Collection Be Worth?, 1989. Offset lithograph, 17 × 22 in. (43.2 × 55.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, Inc., 2017.26.24. © Guerrilla Girls. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Morris and Small were clear that the exhibition was not intended to ‘cancel’ Picasso, but rather to create the conditions for a different encounter with his works – of which there are 100 (albeit some critics claim not important ones) – “in a contemporary moment… this is not a scholarly exhibition. We do not provide answers, we provide a space for a conversation…,” said Small.

It is not uncommon for male critics to struggle when confronted with uncomfortable conversations that challenge the status quo. Their knee-jerk reactions spoke volumes not only of a gender bias but also resistance towards appealing to the mainstream audiences with accessible art curators such as Gadsby and texts paired with the art, such as one that read “Art history taught me that historically women did not have time to think thoughts, as they were too busy napping naked alone in a forest."

Gadsby's "I hate Picasso, but there is Cubism" approach is perhaps basic, puerile even, but no one is throwing the baby out with the bathwater for now. Their efforts to challenge Picasso's legacy and critically reconsider his art in a contemporary context while acknowledging marginalised voices and exposing the deep-seated misogyny that has shaped our society contributes to broader discussions on representation, power dynamics, and the role of institutions in the art world.

Perhaps we need to let a few African comedians loose in our art spaces to kick up some sand and tread where few dare to go.

- Corrigall is a Cape Town-based commentator, advisor and independent researcher.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory