Tracing the threads of abstraction

- By Mary Corrigall

-------------

Moffat Takadiwa, Bhiro ne Bepa (pen and paper), 2023, pen leftovers, computer keys and toothbrushes, image courtesy the artist and Nicodim Gallery

Moffat Takadiwa, Bhiro ne Bepa (pen and paper), 2023, pen leftovers, computer keys and toothbrushes, image courtesy the artist and Nicodim Gallery

An exhibition focusing on textile works is easy to identify. The title typically involves a play on words alluding to the medium. Consider this list of titles of shows; Ravelled Threads, Queer Threads, Narrative Threads, Where the threads are worn and Pulling at Threads. Not only are the titles for these kinds of exhibitions formulaic but to some degree so too are the selection of artists, or works with curators assembling African artists who work with materials, weaving or simply use discarded, disused objects to create a sort of carpet, surface could fit the ‘textile’ category.

One of the less explored aspects of the so-called textile art movement/medium in African expression is an investigation into the use of abstraction and more precisely what artistic, conceptual or ideological value textiles activate via the use of this mode as opposed to say painting. This is despite the fact that artists working with a broad definition of textiles are similarly guided by their materials, the formal features of their works, intuition and, of course, a desire to escape linear or figurative narratives.

While South African-based artists such as Thania Petersen, Billie Zangewa and Athi-Patra Ruga have been celebrated for their figurative textile artworks, on the whole, it is the textile artists working in an abstract mode that dominate and have perhaps enjoyed a higher profile – think of El Anatsui, Joël Andrianomearisoa, Abdoulaye Konaté, Igshaan Adams, Moffat Takadiwa and more recently newcomers such as Bonolo Kavula and Bev Butkow.

Igshaan Adams, Kicking Dust , Kunsthalle Zürich, 2022, installation view, photograph: Annik Wetter

These artists aren’t simply rewiring our conception of abstraction as the preserve of painters but can access and introduce other kinds of qualities and concepts that painting denies. In their use of disused materials and off-cuts Butkow and Takadiwa can interweave layers of social subtext into a mode often thought to be apolitical. The labour required to create textile works demands that the artists have to rely on teams of ‘workers’. This draws attention to not only the relationship between work and art, and the power relationships involved in art production but, more importantly, muddies the notion of single authorship of art-making, albeit that the works produced by Adams, Takadiwa or Butkow are attributed to them as individuals. Yet the works they produce with their teams are the sum of communal engagement with materials over long periods.

Significantly, abstraction via textiles upturns this vocabulary as one originating from white male artists from the West.

Since the emergence of abstract painting – at least according to an outdated version of western art history where male artists are privileged – the dividing line between painted works and textile ones and the definition of art relied on whether the composition was perceived as ‘ornamental.’

Igshaan Adams, Open Production at the A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town, 2020, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundation

Igshaan Adams, Open Production at the A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town, 2020, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundation

“Pioneers such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian looked upon ornament as a sin in which abstraction should not indulge,” posited Markus Brüderlin, one of the curators of the exhibition Ornament and Abstraction: The Dialogue between Non-Western, Modern and Contemporary Art, which showed at the Fondation Beyeler, Basel Switzerland in 2001. As the title of that exhibition hints, due to a strong relationship between expression from the global South and the advent of abstract painting in the West, the painterly mode has been haunted by the 'decorative' arts – clay, wood or ceramic, and textiles. As it emerged from a dialogue with art from expression in the global south.

The dividing line between art and craft was further cemented by the American critic Clement Greenberg who “used the decorative as a critical device to distinguish 'high' abstract painting from 'decoration' defined as a form of surface attractiveness masquerading as art,” observes Elissa Auther in her journal article, The Decorative, Abstraction, and the Hierarchy of Art and Craft in the Art Criticism of Clement Greenberg.

The erosion of these hierarchies, which African art and contemporary artists have contributed towards, has allowed for mediums associated with ‘decorative’ art to be valued. Prizing female artists have also contributed towards shifting attitudes as so much of the prejudice related to so-called decorative arts and textiles was due to it being associated with women. So perhaps it is not unexpected that largely artists working with textiles are either queer men or women.

Igshaan Adams Studio Team an der Arbeit, Igshaan Adams Open Production at the A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town, 2020, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundation

Igshaan Adams Studio Team an der Arbeit, Igshaan Adams Open Production at the A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town, 2020, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundation

In Elizabeth Wayland Barber’s Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times (2005) the American archaeologist was able to establish that women were mostly responsible for the weaving of textiles in primitive societies. Butkow believes that could explain why she feels that making woven art comes so instinctively to her. “It is like giving birth… your body just knows what to do and how to do it,” says the Joburg-based artist, who will stage a solo exhibition, ‘weaving off-grid - re-working m/other’, at the Origin Centre at Wits University. It will be paired with a Creative Laboratory centred on “women's work as artistic practice.”

In the footsteps of Anatsui, Takadiwa doesn’t weave or produce traditional textiles – he tends to use disused mass-produced materials such as toothpaste bottles, and bottle tops from various products sold in his native Zimbabwe. However, his practice remains closely tied to the Korekore weaving traditions in his country that were not only traditionally in the hands of women but were in everyday use by women. Not that Takadiwa has personal experience with this. Interestingly, despite growing up in a rural area, he was not raised to follow traditions. He says he grew up with a "conflict with culture" due to his father eschewing traditions – he opted out of being a chief and the coronation that would seal this status.

Moffat Takadiwa: Vestiges of Colonialism, Installation View, National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare, 2023. image courtesy the artist and Nicodim Gallery

Moffat Takadiwa: Vestiges of Colonialism, Installation View, National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare, 2023. image courtesy the artist and Nicodim Gallery

“My father didn’t want us to associate with anything like witchcraft,” says Takadiwa, who recently staged his first and possibly largest museum exhibition, Vestiges of Colonialism, at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare.

As the title of that exhibition suggests, the artist is interested in drawing attention to the way in which the legacy of colonialism lingers and has shaped Zimbabwe’s current political situation, which he does through the objects that relate to that era. Despite the political intent driving this exhibition, and the many works and installations in it, he opts for an abstract language.

This is not due to any fear that there might be blowback – the Zimbabwean government doesn’t have a good record when it comes to protecting freedom of expression (political journalists are regularly jailed).

“The government isn’t interested in what visual artists have to say,” he says.

Rather, he suggests that abstract expression can have more impact, albeit in a quieter way.

“It allows you to be more subtle. We need to use a clever language and clever ways to communicate. This can be even more powerful,” he says.

As such Takadiwa relies on his choice of materials to introduce the socio-political element, though from afar the large-scale hanging works he creates deny the specificity of his materials and to some degree, some of the subtleties might be lost on outsiders.

For example, he opts to work with mass-produced items that carry class distinctions in Zimbabwe – like the lids of cooking oil bottles or toothpaste tubes.

Growing up in a rural setting, he didn’t have access to these items and “sees them as objects of leisure and class.”

It is also perhaps no coincidence that his father worked at a supermarket and he spent his youth gazing at the items on the shelves.

Butkow’s relationship to her materials is somewhat different – she derives much of her materials from a friend with a clothing business and has less of a personal connection to them. However, in her practice she tries to connect to them physically, letting their ‘materiality’ guide the process.

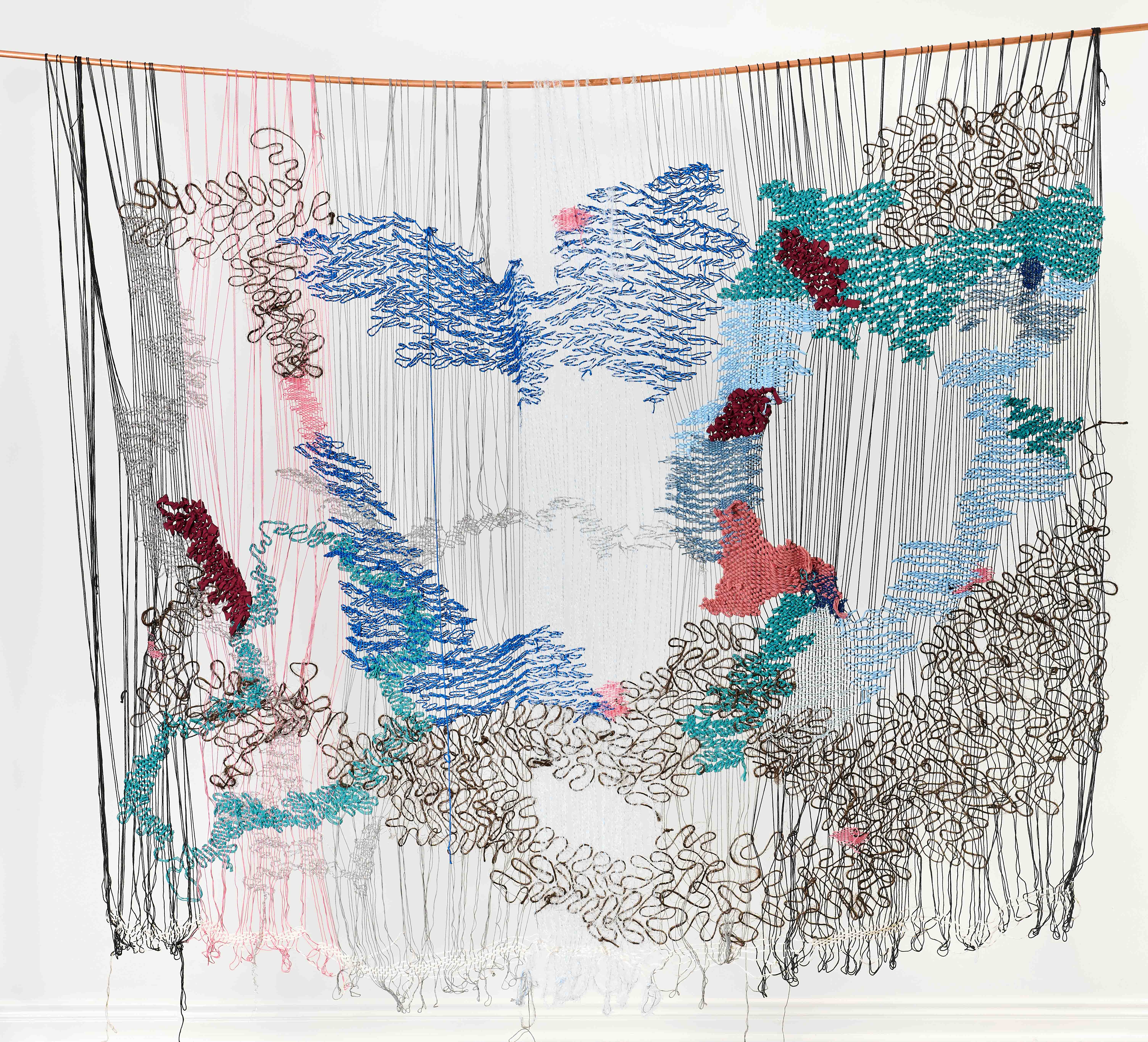

Of generations past, and future - detail, Made with Thandiswa Maxinyane, 2023, Thread, dressmaking scraps, copper rod, time and effort, 380 x 170 cm, Image courtesy Bev Butkow, Guns & Rain, Anthea Pokroy

“I don't have an idea upfront. I'm trying hard to develop a collaborative relationship with my materials,” she says.

Butkow is guided by a quote (from 1944) by Anni Albers, the Bauhaus era abstract textile artist, that reads:

“We learn to listen to voices: to the yes or no of our material, our tools, our time. We come to know that only when we feel guided by them our work takes on form and meaning, that we are misled when we follow only our will.”

Butkow was drawn to an abstract language as she was seeking out “existing in the world in a different way”, which for her not only meant walking away from a corporate job and becoming an artist but embracing a language that offered “multiple perspectives, and multiple ways to see things.”

Bev Butkow, dappled perspectives, made with Thandiswa Maxinyane, 2022, Wool, string, twine, copper rod, time and labour 210 x 210 cm, image courtesy Bev Butkow, Guns & Rain, Anthea Pokroy

Bev Butkow, dappled perspectives, made with Thandiswa Maxinyane, 2022, Wool, string, twine, copper rod, time and labour 210 x 210 cm, image courtesy Bev Butkow, Guns & Rain, Anthea Pokroy

Butkow’s compositions are less compact than Takadiwa’s, yet what is striking about both of their works are the gaps or holes, and openings in their compositions.

“It's referencing the information that lies in the space in between what we see,” suggests Butkow. She says this drive possibly relates to her personal family history. Her grandparents are Jews from Eastern Europe and while they survived the Holocaust, there is “a lack of knowledge about our family going back.”

A cartographic aesthetic also defines the work of several abstract textile artists. Adams has literally dug into this quality. In his show Kicking Dust, which opened at the Hayward Gallery in London in 2021, some of his compositions were inspired by Google Earth satellite images mapping the once-racially segregated borders between Bonteheuwel, where he grew up, and Langa, the neighbouring township.

Bev Butkow, Lines of Flight, Made with Heid Stroh, 2022, String, plastic cord, wooden slats, embodied traces of time/ labour/exertion/conversation/instruction, Approx size 200 x 270 cm, Image courtesy Bev Butkow, Guns & Rain, Anthea Pokroy

Bev Butkow, Lines of Flight, Made with Heid Stroh, 2022, String, plastic cord, wooden slats, embodied traces of time/ labour/exertion/conversation/instruction, Approx size 200 x 270 cm, Image courtesy Bev Butkow, Guns & Rain, Anthea Pokroy

The boundaries and territories that many of these artists depict, however, are not easily contained – their compositions trail off into hanging pieces, lines that trail on the ground or are sometimes large and unwieldy or appear fragile and temporary. These are all characteristics that textile constructions allow for in ways that traditional art mediums such as painting simply can’t. From this point of view, the painted medium appears to limit the possibilities of abstraction, which ultimately is rooted in ambiguity and being open-ended.

- Corrigall is a Cape Town-based commentator, advisor and independent researcher.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory