The Term ‘Emerging’ Might Not Be Serving Artists

The changes in the South African art landscape demand that we revise some of those slippery art world terms, writes Mary Corrigall.

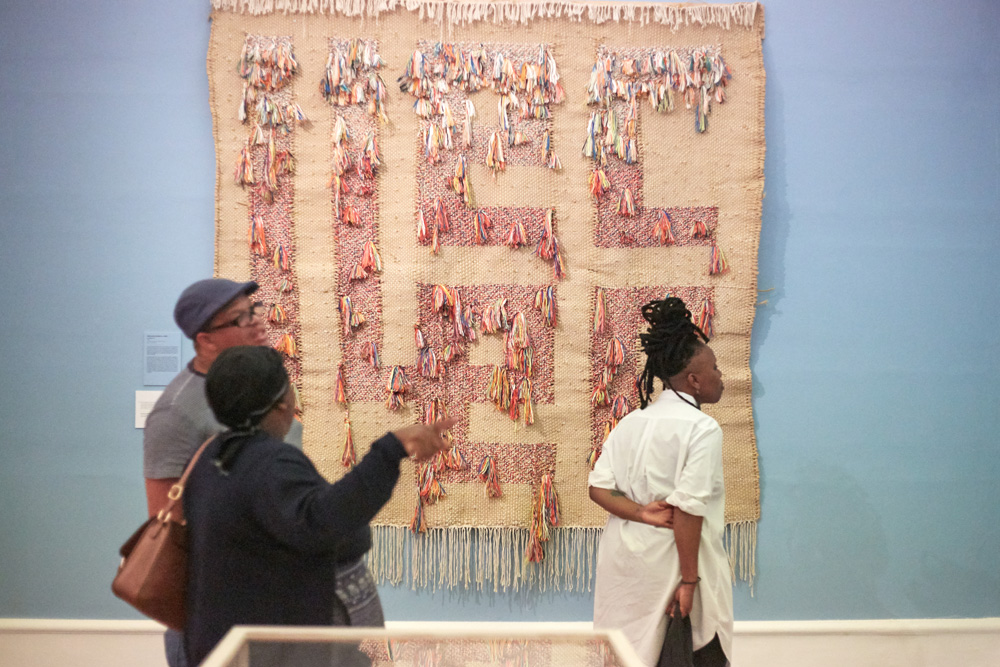

Guests at the opening of 'Filling in the Gaps', which showed at the Iziko South African National Art Gallery. Pic by Marla Burger.

Of all the terms, or euphemisms, in art world parlance that are the most overused surely the phrase ‘emerging artist’ tops the list. Galleries, art award sponsors, art fairs, curators and writers regularly refer to ‘emerging artists’. Who do they mean when they evoke this term? Are they even certain? There are a myriad of perceptions and misperceptions surrounding this ambiguous group of artists.

Some believe it refers to young artists who have just graduated – they have ‘emerged’ from the warm clutches of university. Others, who were buying and promoting art in 80s, use the term to refer to self-taught artists. There was a sense that those artists regardless of their achievements were perpetually caught in a state of ‘emerging’ due to their lack of education or racial identity. Back then the term tended to be attached to Black artists, cultivating a pejorative culture with even well-known artists with an international reputation being dubbed ‘emerging’. Fortunately, this is no longer the status quo and perhaps it is now older self-taught white artists who attract this slippery label. As such over time the term ‘emerging’ is constantly being revised.

In an article titled ‘Well Merged: Emerging Artists at the End of their Era’, which appeared in the Australia Art Monthly (2013), Emily Cormack suggests that the term ‘emerging’ has evolved alongside the development of the art market in Australia. In that country she suggests that ‘emerging’ artists used to be a term applied to those making non-commercial types of works – pertaining to filmic or performance art led practices. It also was applied to young artists too who were experimenting. However, now, given there are a host of funding schemes, collectives, festivals and programmes in that country to support artists – it is possible to be 35 years old and not be signed to a big gallery and be making art. As such Cormack asserts that the term ‘emerging’ doesn’t have an end-goal – recognition – but rather could refer to artists even in their late fifties who follow an independent practice.

In South Africa artists might not have the luxury of opting out of the gallery or commercial driven world of art but similarly our art ecosystem has evolved and grown exponentially. Since 2000 64 galleries have opened in this country. Some of those galleries have subsequently closed, however, the majority remain open and tend to offer what probably might be viewed as art by ‘emerging’ artists. In such a context the term ‘emerging’ has to be revised or possibly jettisoned altogether. The growth of the commercial art scene, the more recent shifts that social media and the internet have brought combined with the globalisation of the art market has meant that our art landscape is more stratified – not all galleries are equal nor could they be as they can now service different echelons of art buyers. So where once there was only room for a few exceptional artists, now our art market can absorb different types of artists at different levels. A blanket term such as ‘emerging artist’ seems woefully inadequate in helping us understand and appreciate artists who are not celebrated but are climbing different levels in their careers.

Various studies I have undertaken along with other researchers have shown that the majority of practicing artists in South Africa are over 35. Given only a fraction of them are celebrated are the rest considered to be ‘emerging’? That is if you define that term as one denoting those artists that are yet to be recognised or their works to be valued highly. This figure is borne out through a comprehensive report commissioned by the Department of Arts and Culture on our visual arts sector undertaken in 2010 where they found the median age of artists to be around this mark too.

Based on these statistics it seems clear that the bulk of ‘emerging’ artists are not spring chickens on the threshold of fame and fortune as perhaps the notion of emerging might suggest but should rather be thought of as ‘mid-career’. ‘Emerging’ seems to imply ‘a potential future’ – the artists have not reached the pinnacle of their trajectory. The likelihood of mid-career artists suddenly blooming is, however, more likely than a new graduate given they have been quietly working on their craft and are hopefully developing their signature aesthetic and concerns.

Take Usha Seejarim, the 47-year old Joburg-based artist whose prominence has come later in her working life. Since winning the Tomorrow’s/Today prize at the Cape Town Art Fair in 2018, she found good representation with Smac Gallery, which led to greater exposure and appreciation of her art. In this way she has perhaps lived up to the notion that this art fair award identifies “artists set to be tomorrow’s leading names.”

Awards shape perceptions of artists with ‘potential’. The Absa L’atelier has embraced a more pan-African remit.

Yet despite the statistics that show that mid-career artists are in the majority, most of our art awards are fairly ageist; either catering to those under the age of 35, or leaning towards rewarding artists with no experience, who have never held a solo exhibition. The Standard Bank Young Artist Award (under 35), the Sasol New Signatures (no solo) and RMB Talent Unlocked (no solo exhibition). This has to some degree perpetuated the idea that ‘emerging’ refers to artists who have never had a solo exhibition and are more likely to be under 35 years old.

At the other end of the spectrum is rhetoric advanced by art fairs and motivated art dealers perpetuating the idea that artists on the cusp of becoming famous are all deemed ‘emerging’. In this way every artist has the potential to ‘emerge’. This is used as motivation to persuade South Africans to buy art produced by artists that are not known, under the guise of missing out on a good investment. In a way such campaigns or sales rhetoric relies on the ambiguity of the term ‘emerging’. The fact that it doesn’t really mean anything specific has indeed helped cultivate new collectors who perhaps might not have had the confidence to buy art by an unknown artist.

The stratification of South Africa’s art landscape was made most obvious in the reinvented Art Joburg Fair, which in 2019 drew a firm line between third and fourth tier galleries. A view of the Gallery Momo stand at the fair in that year. Pic by Karabo Mooki.

Everyone is interested in potential wealth and fortunately now, we have examples – other than William Kentridge - of young contemporary artists whose works can suddenly skyrocket in value almost overnight. Siphiwe Ndzube is perhaps a good example of this. His works increased in value by 100% or more in a five year period. A student work, Sarah & Some Gentlemen, produced in 2014 sold in 2019 at an Aspire Auction for more than half a million. However, Ndzube is perhaps a rare example of an artist who had barely left university before staging his first solo exhibition and then securing representation with Stevenson gallery. Was he ever an ‘emerging’ artist? Or is this how he is viewed in Los Angeles where he is now based?

Indeed outside of Africa’s borders there is a bevy of art collectors and dealers that believe all artists on the continent are ‘emerging’ given the art market here is in its nascence (compared to other European or American art capitals) and this is reflected in the prices attached to art produced in Africa. As such ‘emerging’ is gauged or communicated via prices. In this way the term ‘emerging’ might be defined in relation to the location or context where it is being applied.

The interior view of Igshaan Adams' 'When Dust Settles', which showed at The Standard Bank gallery in 2018, the year he won the award for the banking corporate’s Best Young Artist Award. In the UK, where he is now staging a show, 'Kicking up the Dust', at the Hayward, he is thought of as an ‘emerging’ artist in that context.

It was slightly irksome for example to hear Ralph Rugoff, the director of the Hayward Gallery in London, refer to Cape Town based artist Igshaan Adams, who is currently staging a solo exhibition there, as an unknown artist. Granted he didn’t use the term ‘emerging’ but given his description and notion that this award-winning artist who is also now represented by a US based gallery is ‘unknown’ suggests that such perceptions depend on that terrible centre-versus-periphery binary that haunts perceptions of cultural activities in the global south.

It may no longer be useful to use the term ‘emerging’ or perhaps as I have advocated previously, it can only be viewed as an umbrella term under which different more precise terms could be used to understand not only where an artist is in their practice but how they are perceived in the global art market. A newly graduated artist is different to a young artist who has a few solos under their belt, or a mid-career artist who isn’t represented by a gallery and sells works for high prices at auctions. Those are some of the realities. What of artists whose practice doesn’t result in shiny things to sell at all and exist on residencies or commissions for installations or performances at biennales? We can’t lump them all together under this one slippery term even if it is an elastic one.

– African Art Features Agency funded by the National Arts Council of South Africa.

The Latitudes art fair which was established in 2019 in response to market-led needs in the art sector, has come to focus on the support of artists at all levels. An installation view at the fair in that year featuring the work of artist Sthenjwa Luthuli. Pic by Thys Dullart.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory