Speaking Art’s Language

- by Timothy Gawaya

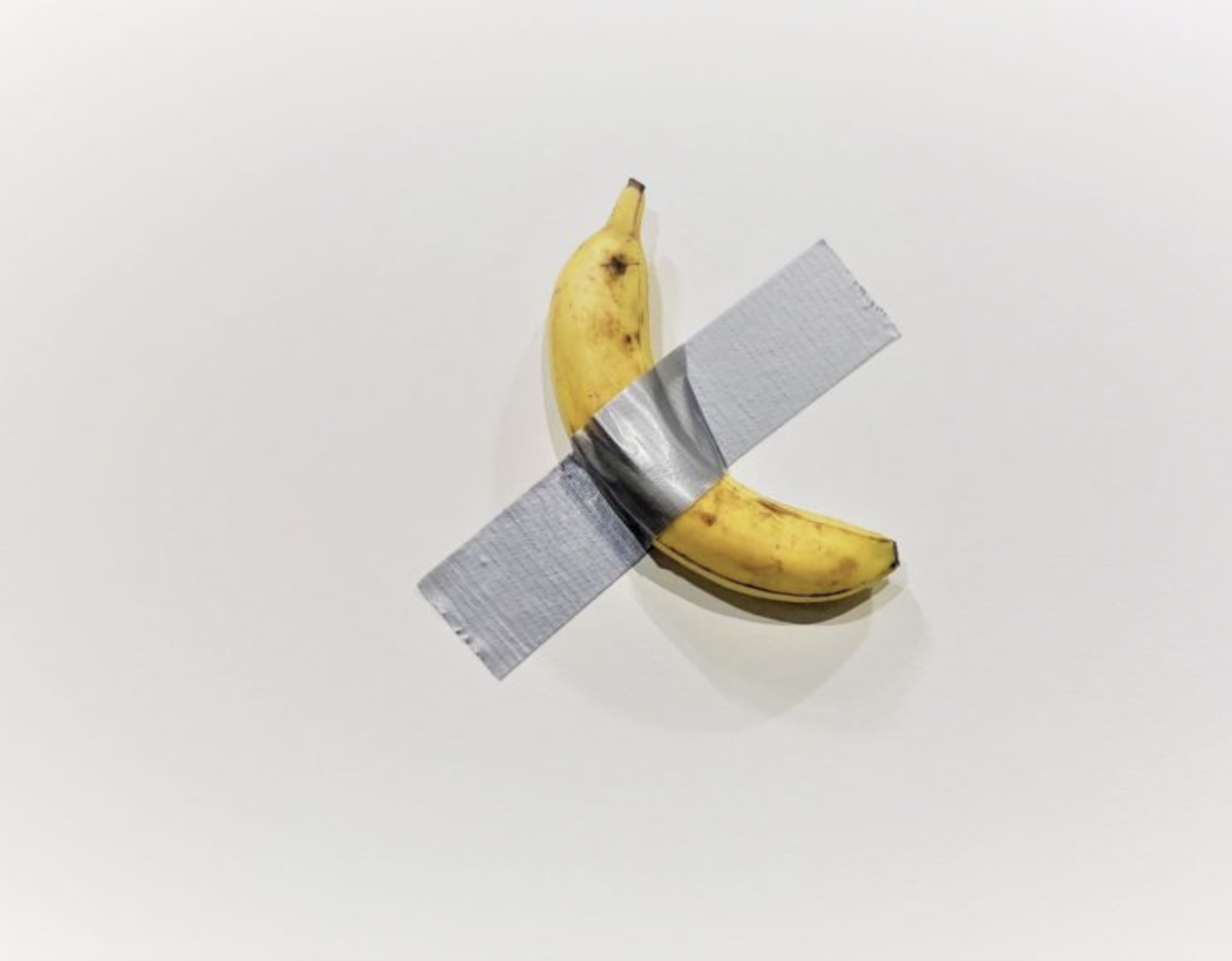

Photo: © Sarah Cascone. Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan on display at Art Basel Miami, 2019. Courtesy Artnet News.

Photo: © Sarah Cascone. Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan on display at Art Basel Miami, 2019. Courtesy Artnet News.

Contemporary art is often criticised for its gradual abandonment of visual coherence in favour of the abstract. This is a common point with which we are all intimately familiar, namely, that much of what is considered ‘art’ today does not make much sense – that a toddler, or even an ape, could’ve splashed a few dollops of paint on a canvas. A long standing charge levelled against artists is their tendency to complicate, or perhaps blur, understandings of artistic merit. People incredulously ask how such and such can be art when it so clearly is, say, a large monochromatic canvas, a urinal, a banana duct-taped to a wall, or a JPEG of an ape.

Those who encounter works in art galleries, exhibition catalogues or online and wish to decipher the visual cues with which they are faced instinctively turn to the text. One would imagine that a descriptive essay should elaborate on how and why this piece with which I am presented qualifies as a work of art. Turning to the text becomes a vestige of salvation, a final hope that things may become less muddled. After all, writing is, in some regards, the conveyance of information. Such that it makes sense that, in a situation where my eyes deceive me, I can turn to the other’s words for clarity.

However, text descriptions accompanying artworks are notorious for their obscurantism and verbosity, often tangentially relating to the works in whose service they claim to be working. The language tends to be highbrow and academic, fond of technical jargon (‘positionality’, ‘non-spatial’, ‘entropic’ etc.), totally unwilling to speak in clearer terms. A specialist’s language. In either case, whether apprehending the artwork or its descriptive text, we are left asking: …what?

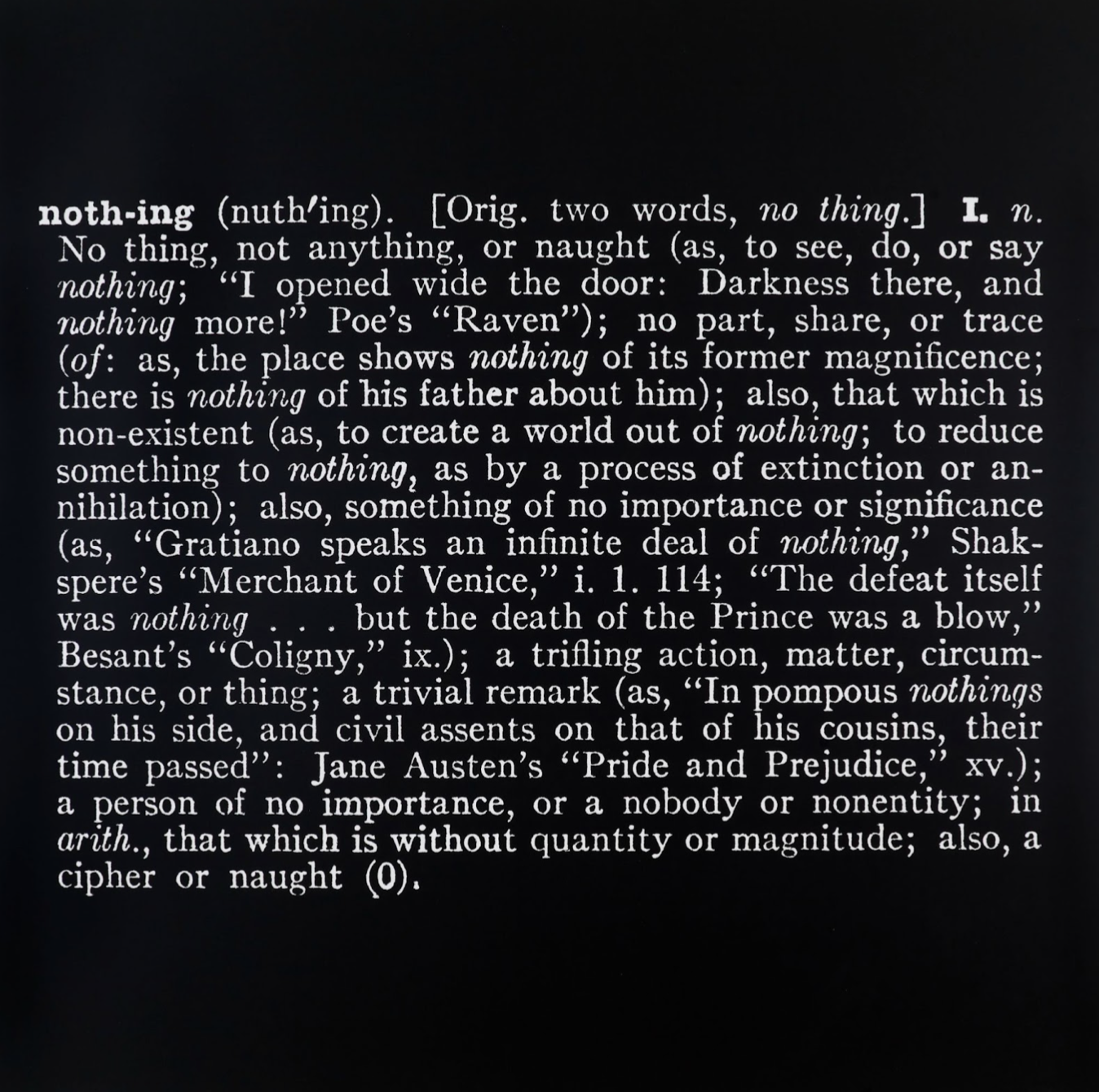

Photo: Titled (Art as Idea as Idea) [Nothing in English], 1968, by Joseph Kosuth. Courtesy Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

Photo: Titled (Art as Idea as Idea) [Nothing in English], 1968, by Joseph Kosuth. Courtesy Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

In other words, contemporary art’s pretentious dimensions have expanded to include its explanations. This is art because it is art: we’re trapped in a tautological circle. Not only could a child have produced this, but words used to mean things, you know. The greater the waffle, the worse the art; right?

‘International Art English’ (IAE) was coined a decade ago by Alix Rule and David Levine to describe a sort of ubiquitous art writing that “has everything to do with English, but [is] emphatically not English.” Rule and Levine attempted to account for the peculiar language seen in press releases, artist’s statements, and gallery texts. Per their argument, contemporary art writing lavishes in obscure language that has ceased being informative and become ornamental. Power and authority are at play here; IAE demands recognition:

“Authority is relevant [...] because the art world does not deal in widgets. What it values is fundamentally symbolic, interpretable [...] The ability to evaluate—the power to deem certain things and ideas significant and critical—is precious.”

The main takeaway is that IAE, or artspeak, has a function that forgoes information: “the goal is to evoke preconfigured conceptions or emotions about art in the reader”. In so many words, artspeak encourages us to ask less what the text means, and more how the text looks. Deliberately emphasising form over function highlights the removal of art from wider society, enclosing it in the confines of the select few.

It might be the case that artistic texts as they exist in their ornamental form maintain and perpetuate socio-cultural stratification. Once artists, writers, and other cultural producers retreat into ornamental obfuscation, the grounds for an effective politicisation of aesthetics become obsolete. IAE invents the layperson as much as the specialist through exclusive means often dictated by access to higher education and cultural institutions. Decoding the text is analogous to decoding one’s position in a social hierarchy.

Photo: © David Shrigley. Stop It by David Shrigley, 2007. Tate. Courtesy Tate Modern

In this sense, IAE reveals as much about your own background and upbringing as it does about the state of contemporary art. Artspeak, like the gallery form, is a successful export that evades all forms of meaningful critique by incorporating politically-subversive rhetoric and anticipating its usage. As Hito Steyerl notes, IAE’s emphasis on ornament “is an accurate expression of social and class tensions around language and circulation within today’s art worlds and markets: a site of conflict, struggle, contestation, and often invisible and gendered labour.”

Speaking art’s language is essentially saying nothing while laying claim to everything. The tension between elaborating art’s politicised dimensions while adhering to the stylistic confines of IAE effectively nulls any critical gestures. IAE is the language of art in its commodity form, allowing us to seem more profound than we actually are. It provides us with the vocabulary for critiquing repressive systems, yet in turn represses our ability to envision art worlds untethered to movements of capital. Take the following example:

[This exhibition] seeks to be a pulsating nerve centre through which the artist embraces a looming metamorphosis of self. Broaching from long standing ouvre [sic] marked by theme attractions [sic] around mental wellness and self-portraiture, [the artist] exhibits a body work [sic] that bids farewell to an ego whose gravitational core is in the past whilst simultaneously beckoning a new horizon in which a new version of selfhood is in waiting.

A surface-level effort at subversive rhetoric accompanies layers of literary concealment. In effect, the above exemplifies IAE’s mutation of linguistic norms: the text masks the emptiness at the root of its statements through flowery language. IAE alienates general audiences as much as it alienates art from its potential as serving political transformation.

The inseparability of art and politics makes questioning IAE all the more worthwhile. If, for example, we have a highly-politicised art that speaks in a specialist’s language, what does it suggest about the efficacy of resisting and reevaluating the strenuous effects of capital? Is it only a matter of decrying things outwardly, while remaining inwardly content with the status quo? Simply put, should we maintain the cynic’s cool distancing, congratulating ourselves with smug analysis at the expense of effective action? Art that exists in commodity form can only outline potential channels of escape, as opposed to a total revaluation of an oppressive system. And artforms that rely on IAE can only lead us so far in our search for a less exploitative regime.

Notes:

Exhibition text: ‘Pride Comes Before The Fall’. Courtesy of USURPA gallery and Nifty Gateway.

Rule, Alix and Levine, David. 2013. “International Art English.”

Steyerl, Hito. 2013. “International Disco Latin.”

Unbehaun, Pascal. 2021. “Artspeak. The Bullshit Language of Art.” in The Polish Journal of Aesthetics.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory