Remembering When Life Got Still

Is still life the artwork of these times?

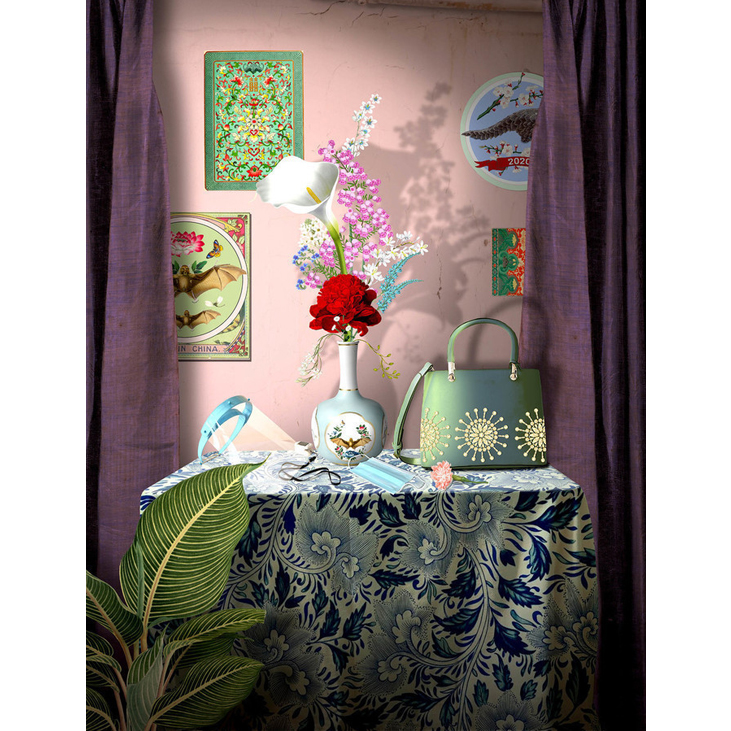

Katharien de Villiers, Calling All Gods II (in between everything else i hope someone is praying), 2020. ENQUIRE.

It’s been over a year now since the world was forced indoors. With our movement restricted, our focus was drawn to what existed within our four walls. For those with internet access, escape could be found through our screens but with the frequency of virtual gatherings for work or for play, this quickly lost its novelty. Our immediate surroundings once again drew focus. At least one magazine at the time optimistically suggested rearranging the objects in your home to have something new to look at.

Long before the pandemic though, the fashionability of still life was on the rise in photography, thriving on image-sharing applications like Instagram and Pinterest. The need for visually interesting ways to market products on these platforms could be one reason for the commercial popularity of this art form. Still lives featuring luxury goods were reminiscent of Irving Penn’s still lives mixing food and fashion for publications like Vogue in the 1980s; another era where materialism was rife. Another reason still life has reached the mainstream could be related to the acceleration of food-related media, content and publishing seen in the last decade or more; food being a mainstay of still life for centuries. During lockdowns around the world, however, with street photographers kept indoors, and portrait photographers socially isolated, still life, in this medium in particular, exploded. Groceries, recycling and toiletries became subjects as we pondered our new reality.

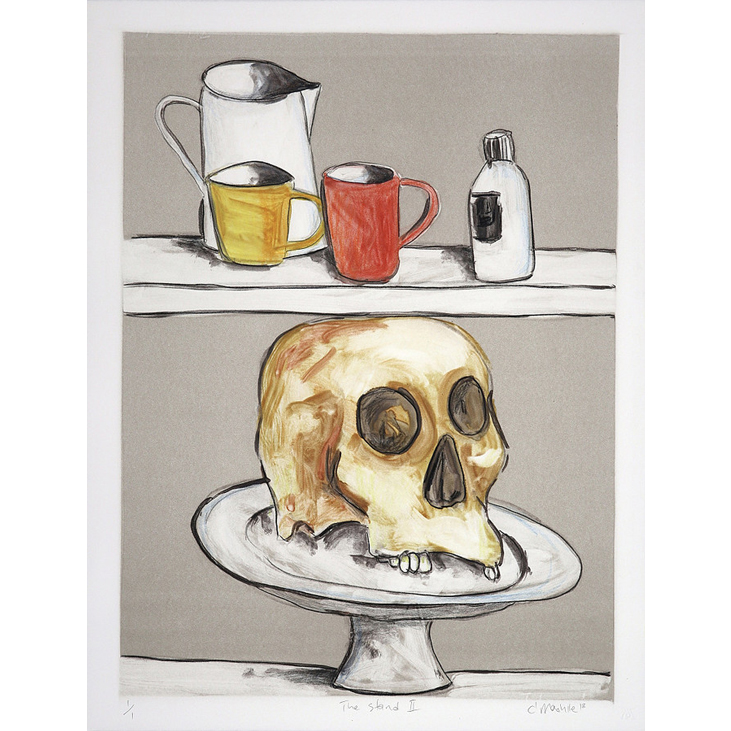

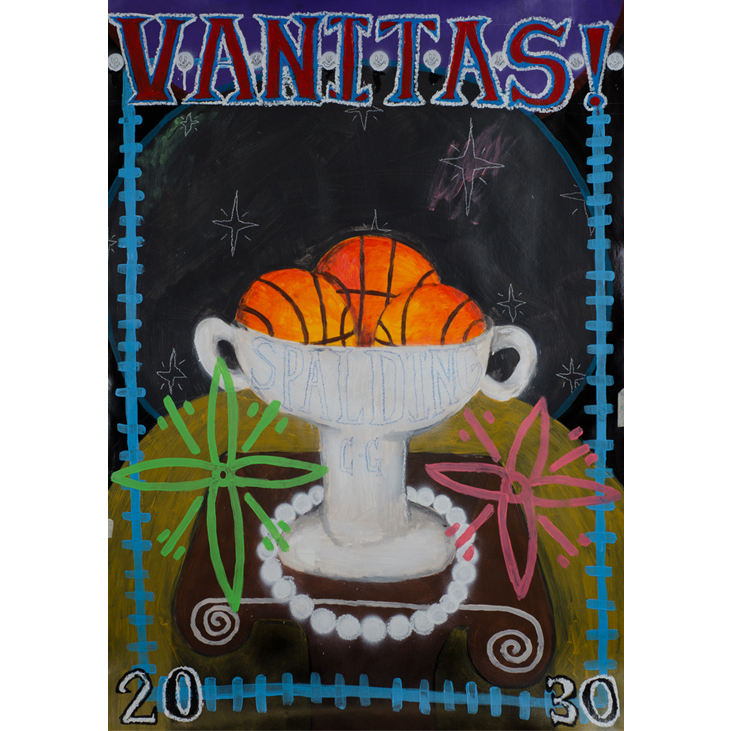

Throughout history images of objects have been used as symbols of mortality or in relation to death. In ancient Egypt, food and belongings were painted onto the inside walls of tombs, believed to become real possessions for the deceased in the afterlife. In Vanitas paintings, a genre of still life painting from the early 17th century Netherlands, objects like skulls, burning candles, clocks, fruit and flowers were used to symbolise death, time passing and nature’s cycles. Perhaps still life’s proliferation over the last year also has to do with the sudden reckoning with our own mortality and the time to muse on our earthly existence and the objects that make up the totems of our lives.

Today, still life blurs the line between commercial image-making and art. It doesn’t belong to any singular world or medium; used both to sell a luxury watch and to study a vase of flowers in oils. Contemporary artists continue to use still life as a formal exercise in composition, form and light but also use objects to document or comment on our lives in the 21st century. The photographer Thirza Schaap uses the beauty of still life to confront people with an ugly truth through her attractive arrangements of plastic she’s collected off beaches and coastlines. Others use it to highlight the bizarre and the beautiful found in the mundane.

In the 18th century, the theory of the hierarchy of genres ranked still life as having the lowest prestige and cultural capital, trailing behind landscape, history painting or portraiture. Even today, it may not seem important but it’s certainly enduring. We may very well look back and find the humble still life, a shrine to the minutiae of our lives and the mysteries of death, to be a symbol of a year that changed our perspectives.

Lee-Ann Heath, Fancy Anthurium. ENQUIRE.

Callan Grecia, Vanitas!. ENQUIRE.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory