Radically astonishing, and astonishingly still radical

Artists are using watercolour in ways that link them to a radical tradition

- by Sean O'Toole

The other day, I visited auction house Strauss & Co to look at a watercolour monotype of an unpeopled landscape in the Kruger National Park by Durant Sihlali. The company plans to sell later in this month. “Unnnnggggghhhheeeee!” I mouthed like a dumfounded character from a Tom Wolfe novel. A work by Sihlali, especially one of his urban watercolours or later monotypes, has the capacity to do that, render one inarticulate, capable only of comic-book outpourings of surprise and delight.

Durant Sihlali, Sunset Kruger Park, undated, watercolour monotype on paper, 19 x 25cm. Courtesy Strauss & Co

Durant Sihlali, Sunset Kruger Park, undated, watercolour monotype on paper, 19 x 25cm. Courtesy Strauss & Co

Can a watercolour astonish? Hell, yes! Have you looked at the work of Lebogang Mabusela and Chloë Reid? Mabusela makes wonderfully garish watercolour monotypes, often on pink grounds. A recent series in this style depicts proud young men wed to their gusheshe (many seasons out-of-date BMW E30). Cape Town artist Igshaan Adams is a big fan. He showed me a bunch of Mabusela’s postcard-sized monotypes at the opening of Breakroom, a new project space inside his spiffy new studio in Salt River.

In 2022, Mabusela exhibited watercolour monotypes from her on-going series Johannesburg Words (2021–) at Stevenson, Johannesburg. Inspired by a 1987 etching by Robert Hodgins titled Jo’burg Words and rendered in a similarly cartoonish style, the series documents lingual examples of catcalling faced by black women in Johannesburg. Hodgins, who satirised self-important captains of industry and bullying generals, offered a Mabusela a model to think about how to portray misogyny. “It shows that calling things out is not only part of a Black woman’s identity. White men also complain about shit all the fucking time.”

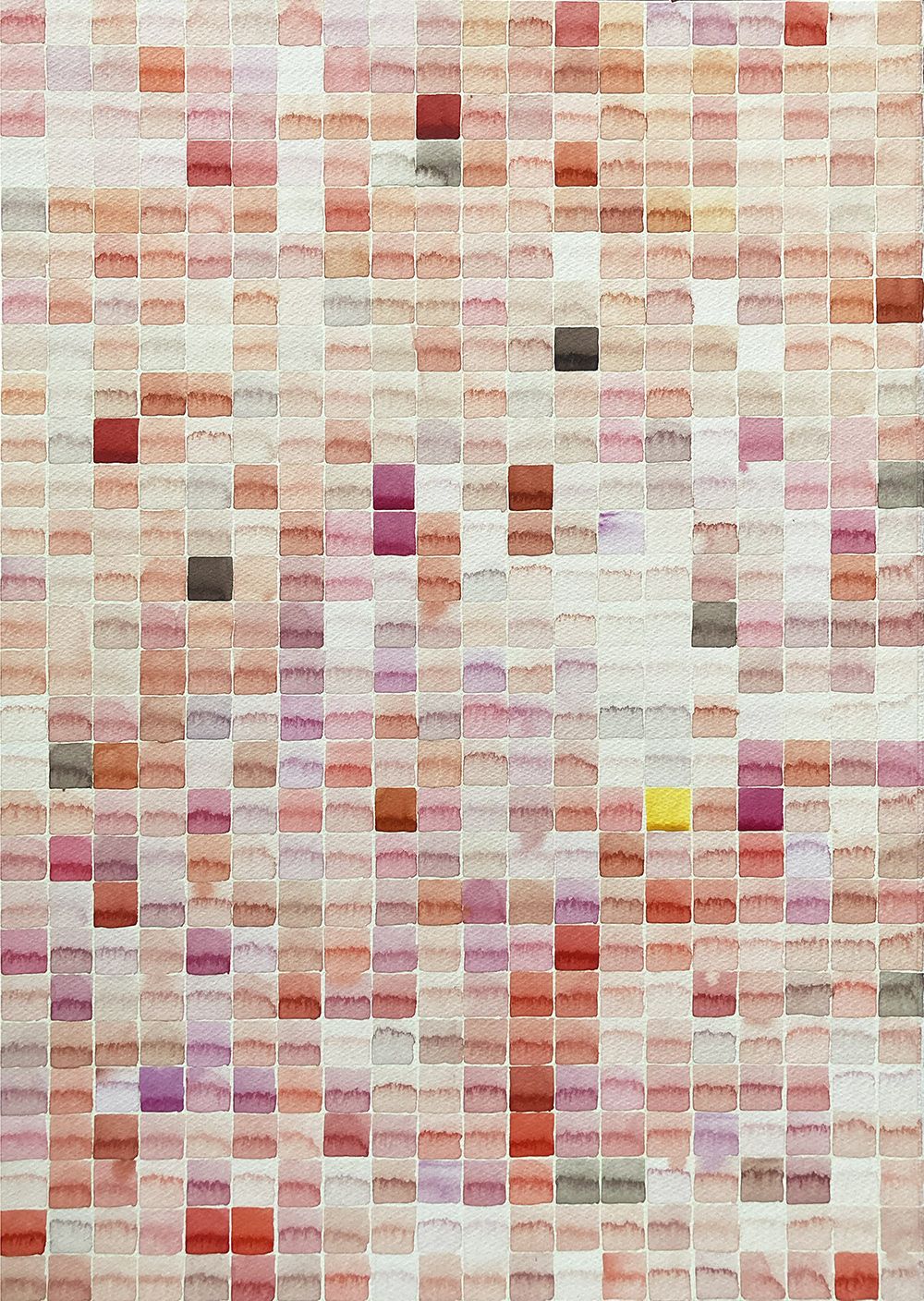

Chloë Reid, Untitled (pink), 2023

Reid, by contrast, is an abstract painter. Since 2019 she has worked on an on-going series of watercolours depicting the geometric tile arrangement of walls and floors in Johannesburg. Amazing. I own one. She was drawn to the medium for practical reasons. “I wanted to speed up the making process and force myself to loosen up,” says Reid. “Before then all of my work on paper was very labour intensive – detailed colour pencil drawings that take months to make. Sometimes I feel the weight of that labour hangs over the work. It imbues the work with a kind of false significance because it took so much effort to make. Watercolour is immediate, at least the way I use it. I rarely go over a mark once it's down.”

Although I’m sure Mabusela and Reid will laugh out loud at this, their notational watercolours, at once casual and highly focussed, experimental yet affordable, link them to a tradition of radical watercolours by a cohort of dead men. I think here of Walter Battiss, Allan Crump, George Pemba and, of course, Durant Sihlali. Why “of course”? Germiston-born Sihlali, who died in 2004, is an irrefutable figure in the story of art in twentieth-century Johannesburg. Period.

Lebogang Mabusela, Ushadile?, R 3,000.00 ex. VAT, ENQUIRE

Lebogang Mabusela, Ushadile?, R 3,000.00 ex. VAT, ENQUIRE

The artist and teacher Colin Richards, himself a fine watercolourist, wrote of Sihlali in an admiring obituary that he was as “one of the few contemporary artists who lived through the early years of the building of contemporary South African art”. Richards doesn’t mean that Sihlali was around to see the first Johannesburg Biennale in 1995. “He experienced first hand many of the key institutions and events widely held to be formative of the experience of black artists in the decades of apartheid and just before,” wrote Richards, expanding the sense of contemporary to include the Polly Street Art Centre, which Sihlali briefly attended circa 1953.

Dogged endurance and being a scenester are no guarantees of a legacy. For all the astonishment his watercolours possess, Sihlali remains, as Richards put it two decades ago, “uniquely neglected”. This condition sadly endures. Family complications around Sihlali’s estate following his death are partly to blame. It doesn’t help that some of the artist’s finest achievements are expressed in a supposedly lesser medium: watercolour on paper.

Like his senior, George Pemba, Sihlali was a technically gifted artist who initially committed himself to working in a very traditional medium in a naturalist style. Notwithstanding his late-career experiments with papermaking and frottage, Sihlali is still best known among his admirers for his large body of realist watercolours made en plein air from the 1950s into the early 1980s. His subjects included old Pimville, working life in the various mines surrounding Johannesburg, the view from Chapman’s Peak onto Hout Bay, even an unpeopled landscape in a racially segregated nature reserve.

Sihlali’s approach to painting – in the open, wherever he liked – remains radical. Radical because, as the artist told Joy Kuhn in 1974, his paintings refused aestheticism in favour of fact. “I don’t think I paint artistically,” explained Sihlali. “What I’ve been interested in doing is recording what is around.” This philosophy extended to rural landscapes, including in the Kruger National Park. It is unknown when Sihlali visited this vast wilderness, and even whether he stayed overnight. Although open to all race groups, racial mixing in campsites had been proscribed since 1932, when Balule was established on the south bank of the Olifants River to cater for African and Indian visitors.

What to make of this unusual monotype? It is indisputably gorgeous as well as important. Sihlali made his earliest monotypes on the 1960s. His later use of colour in his monotypes introduced a sensitivity that evoked the chromatic elegance of his watercolours. The print medium enabled Sihlali in new ways, allowing him to experiment with line and washes of pastel colours, in effect to invite abstraction into his work. But the work is also an important visual correlative to an evolving body of research discussed by historian Jacob Dlamini in 2020 book Safari Nation. The book is a sweeping historical account of the park, but as Dlamini explains it also aims to offer critical reflections “on the existential state of black tourism in South Africa”.

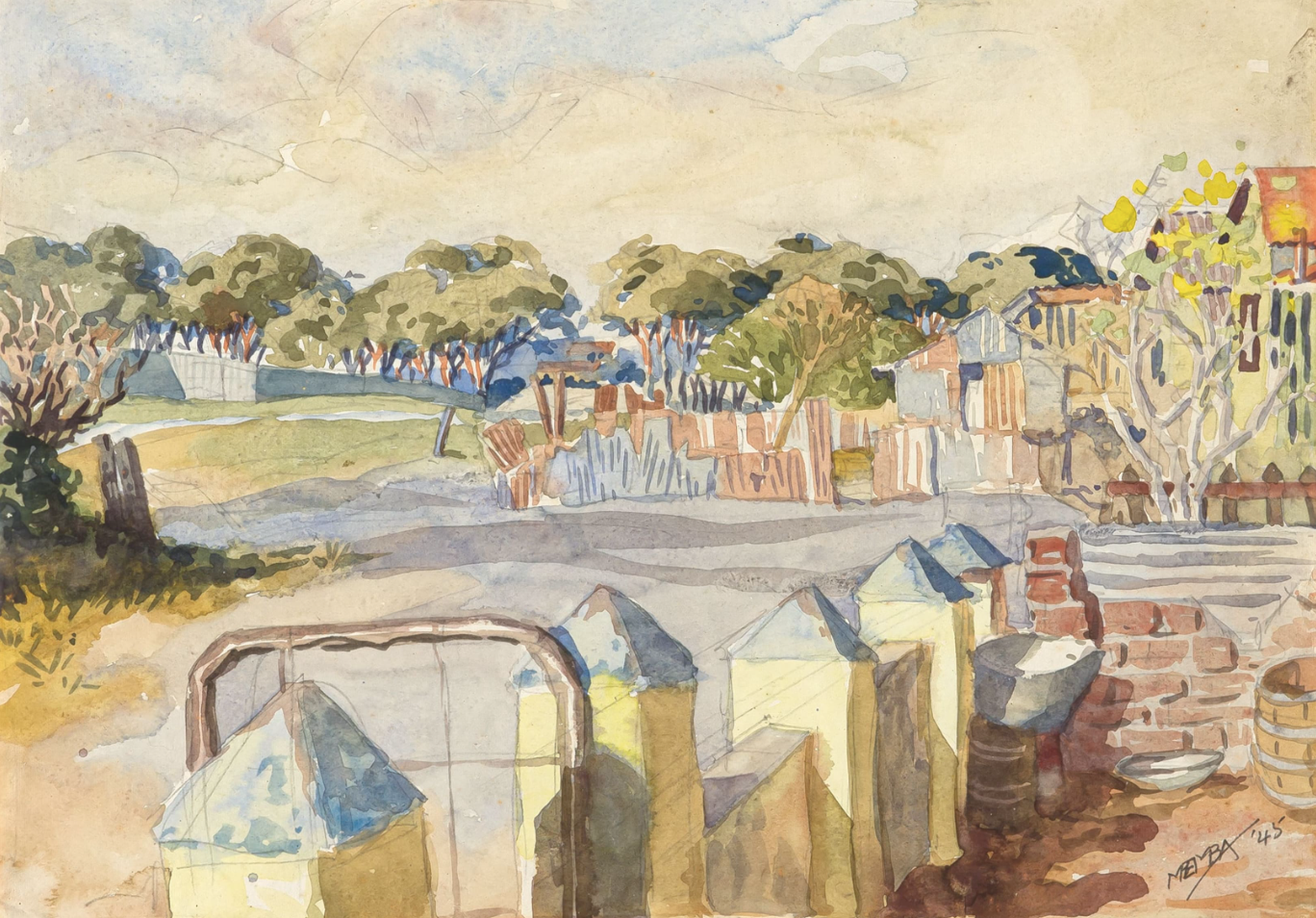

The story of South African art is, in certain respects, a story of travel, of artists leaving the humdrum of their everyday lives and rubbing up against the commotion and novelty of other places. In October 1944, while still working as a court interpreter and clerk in New Brighton, George Pemba took a leave of absence in order to travel the country by train. After a stopover in Cradock, where he visited his sister, he journeyed to Johannesburg. “Activity, haste, masses of people, excitement, shining colours, glittering sunlight,” he summarised.

From the Big Smoke he pushed on to Ladysmith, followed by Durban, Mbumbulu and Basutoland, where Pemba recognised a resistant spirit and freedom also acknowledged by Sol Plaatje during his heroic 1913 travels. His last stop was Mthatha. Throughout he made watercolours, sensitive studies of singular people that astonish for their quiet dignity. In doing this Pemba was plainly disobeying the advice of his friend, Gerard Sekoto, who in 1942 told Pemba that watercolour was a fusty English medium that commanded lower ticket prices. Just stop.

Walter Battiss, Vaal River, signed and inscribed with the title; E. Schweickerdt label adhered to the reverse, watercolour on paper laid down on card, courtesy Strauss & Co.

Walter Battiss, Vaal River, signed and inscribed with the title; E. Schweickerdt label adhered to the reverse, watercolour on paper laid down on card, courtesy Strauss & Co.

Sekoto favoured oil on canvas, the material of modernity and Paris. Pemba, who never travelled abroad, listened to his pal, but only gradually obliged his counsel. The death of watercolour, at least in South Africa, could well be dated to Pemba’s eventual favouring of oil by the early 1950s. Or not. Perhaps it died in 1987, when Sihlali returned from a six-month residency in Nice, France, and announced he had discovered his “true identity”. That new identity was haunted by the past, by his ancestors, their mural traditions. Much like Mawande ka Zenzile in his current show with Stevenson, Cape Town, Sihlali went abstract. He also ditched watercolour.

The story of watercolour in South Africa is conventionally narrated as one of youth, necessity and experiment, bookended by graduation. Very much like Frans Oerder, a Dutch-born realist painter transplanted to Pretoria, who in 1896 visited rural Zululand, producing fine notional watercolours, Battiss and Pemba graduated to oil. Sihlali became a mixed-media experimentalist. The fluidity of youth, the narrative goes, is supplanted by the seriousness of oil. But this pat story doesn’t always square with reality.

Take Alan Crump. A former studio assistant to Vito Acconci and Richard Serra, Crump ditched his early interest in minimalist sculpture in favour of watercolour painting. His 1980 move to Johannesburg – where he was the terror or treasure (accounts vary) of Wits University’s art department – introduced him to its brutalised mining landscapes. Crump devoted much of the early 1990s to portraying these unpeopled places. “Though these diggings are devoid of people,” wrote Crump, “they remain testaments to extensive human activity.” Watercolour – the medium of radicals like William Blake and J.M.W. Turner – offered him a delicate, unruly matter capable of rendering these “wrecked, distorted and carved wastelands”.

Alan Crump, The Mine, 1997, watercolour on paper, 107 x 152cm. Courtesy Johannesburg Art Gallery.

Alan Crump, The Mine, 1997, watercolour on paper, 107 x 152cm. Courtesy Johannesburg Art Gallery.

If the medium of watercolour were a thing capable of speaking back to us, what would it say? Would it speak in the voice of an enthused child extemporising on the identities of brightly coloured stick people? Or would it sound old and boring, like Mos Def demanding “see me, hear me” on Grown Man Business in 2004. I like to think that if watercolour had a voice, it would be clear and even, not Karen shrill. It would have the “incredible precision” of Sihlali when he met a visitor. And, importantly, it would be defiant. “The reports of my death,” it would say, “are greatly exaggerated.”

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory