Photography, not quite mainstream, is always emerging, always surprising

- By Sean O’Toole

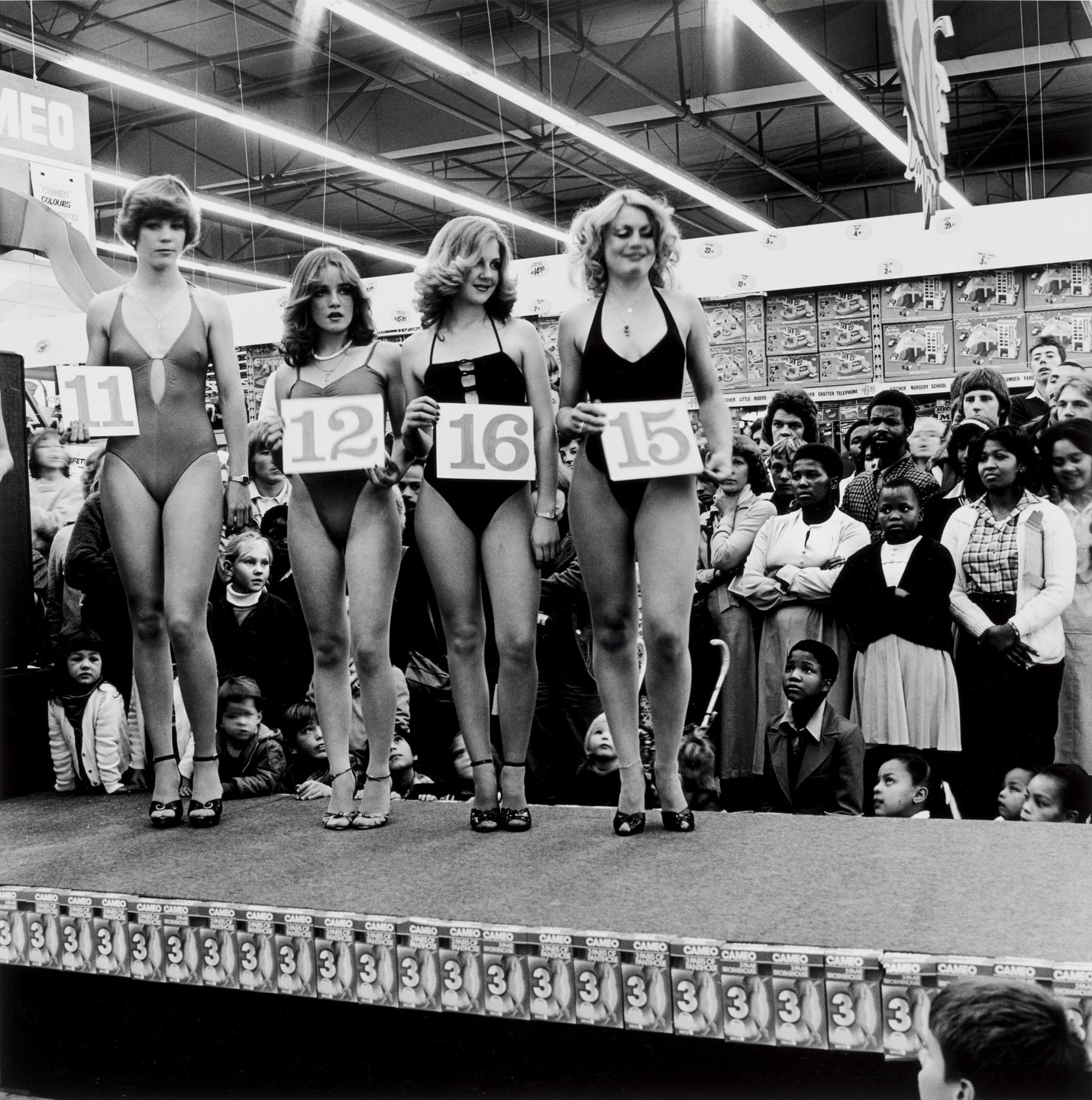

David Goldblatt, Saturday Morning at the Hypermarket, Semi-Final of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, 28 June 1980. Courtesy The Goodman Gallery & David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt, Saturday Morning at the Hypermarket, Semi-Final of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, 28 June 1980. Courtesy The Goodman Gallery & David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

It is perpetually summer and winter with photography from South Africa, the news both good and bad, all at once. On the upside, there is much to be enthused by. A new generation of photographers, among them Tatenda Chidora, Lebohang Kganye and Lindokuhle Sobekwa, are exhibiting widely, publishing well-received books and winning prestigious awards. Sobekwa, 28, is especially blazing a trail.

In January, Johannesburg-based Sobekwa received the inaugural John Kobal Foundation Fellowship, a major new art prize awarded biannually to an artist or collective who for “an outstanding body of lens-based work”. Sobekwa will be London next week (30 March) to deliver his fellowship lecture at Tate Modern, the same institution that in 2020 hosted the first major UK survey of visual activist Zanele Muholi.

Sobekwa is currently showing work in Johannesburg with his hero, documentarian Ernest Cole. Against the Grain at Goodman Gallery is an intergenerational exhibition of photography that also features David Goldblatt, Ruth Motau and Ming Smith. The exhibition coincides with a South African roadshow to promote a new edition of Cole’s seminal 1967 photobook, House of Bondage.

Zanele Muholi, MuMu XIX, London, 2019

Zanele Muholi, MuMu XIX, London, 2019

A scrupulous exegesis of black life in apartheid South Africa, New York-based Aperture Foundation recently reissued House of Bondage in a new edition that includes a chapter of never-before-seen photographs of black creative expression and cultural activity taking place under apartheid. A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town will host a book launch on 23 March.

Equally encouraging, veteran photographer Roger Ballen has opened a new private museum in Forest Town, Johannesburg. Designed by architect Joe van Rooyen of JVR Architects, The Inside Out Centre for the Arts will fly the flag of contemporary African photography courtesy of Ballen’s longstanding association with the Eiger Foundation in Switzerland. Ballen has been a keen promoter of photography, in the past sponsoring exhibitions by visiting photographers Stephen Shore and Vik Muniz at public museums in Johannesburg and Cape Town, as well as underwriting seminars to advance the criticism of photography.

Tatenda Chidora, Self Isolation I, 2020, from the series 'If Covid Was A Colour', winner of Portrait of Humanity Volume 5

At face value, things appear buoyant. But a lacklustre market for print sales weighs heavily on the doings of photographers. Sales, it is quietly whispered, have been tepid since 2020. These anecdotal remarks are backed up by hard data. Research conducted by Irish consultancy Arts Economics on the global art and antiques market in 2021 found that the bulk of the estimated $34.7 billion generated from global sales in the dealer sector came from the more traditional mediums of paintings, sculptures and works on paper. Photography only accounted for 5% of total sales.

Photography has always been something of an outlier collectable in South Africa, its orphan status reaffirmed at the recent Cape Town Art Fair. Of the more than 50 exhibitors, only three committed budget to go-for-broke solo presentations of editioned prints by Philippe Koudjina (Thomarts Gallery), Johno Mellish (THK Gallery) and Lunga Ntila (BKhz Gallery). Other dealers, mindful of the lacklustre market for photography, presented new work by Nicola Brandt (Guns & Rain) and Tony Gum (Christopher Moller Gallery) in mixed presentations of stable artists.

So how did these plucky dealers fare?

Ntila’s photo-collages, now a rarity following her premature death in 2022, were mostly presold. BKhz Gallery’s art fair presentation partly served as a posthumous tribute and featured work traded in Ntila’s 2021 exhibition God Among Us. A week after the fair, auction house Strauss & Co realised R35,175 for a 2019 self-portrait by Ntila published in a single edition, with two additional artist’s proofs. A bargain price, all things considered.

Lebohang Kganye, Staging Memories, 2022, detail of installation for award show for Images Vevey Switzwerland Photo Emilien Itim

Lebohang Kganye, Staging Memories, 2022, detail of installation for award show for Images Vevey Switzwerland Photo Emilien Itim

Brandt’s two interlinked bodies of work Fire and Physical Energy, both made in the environs of Rhodes Memorial circa the catastrophic fire that engulfed Table Mountain and the University of Cape Town in 2021, generated “several sales,” according to dealer Julie Taylor.

“Local visitors, including a fire-fighter couple who had helped quell the blaze of April 2021, could immediately relate to their own geographic environment and in turn to its history, both political and ecological,” says Taylor, who has opened a new Johannesburg space in Parkhurst. Brandt’s photos were priced between R26,200 ($1,470) and R69,000 ($3,880), depending on size, and were offered in an edition size of five plus one artist’s proof.

Black-and-white prints by Koudjina, a respected independence-era photographer who favoured scenes of conviviality in Niger’s capital Niamey, were priced at R23,000 (€1,162). The edition size was limited to ten prints. Ngulube reported satisfactory sales, but is still following up with “cautious spenders” and those “not well versed on the value of photography”. Reviving a debate around colour photography in the 1990s, Ngulube speculated that black-and-white photos put off collectors, in part due to their association with historical news images of “struggles and protests”.

Black-and white prints from Mellish’s new essay Wild Natural Setting, an impressionistic juxtaposition of found and composed scenes set along the Garden Route, struggled to find buyers. Offered in an edition of eight, the uniformly large prints were priced at R42,000 ($2,250) each. Emboldened by the favourable critical response to Mellish’s work, THK Gallery is considering returning to Paris Photo in November with his work.

The recent uneven trade in Cape Town, while hardly catastrophic, recalls some of the complications and nuances that underpinned the remarkable upsurge in interest in South African photography after 2000, both locally and internationally, institutionally as well as at market. David Goldblatt, who died in 2018, was a leading figure in this tidal upsurge. A closer look at his later career offers a case study in the contradictions underpinning the market for collectable photography.

David Goldblatt, Self-portrait at Consolidated Main Reef Mines, Roodepoort, May 1967

In 1998, at the age of 67, Goldblatt presented a solo exhibition of 40 architecturally themed works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was the first such achievement by a South African artist. Bigger surveys soon followed, notably Fifty-One Years (2002), which featured 220 photographs produced between 1948 and 1999. Originated in Spain, the travelling exhibition was co-curated by Okwui Enwezor, who included Goldblatt’s new colour work in his watershed documenta 11, also in 2002.

The art market was quick to respond. In 2002, the Goodman Gallery hosted a solo exhibition of new and old work by Goldblatt. The presentation included vintage black-and-white prints depicting views of Soweto and District Six, some of them one-off vintage prints. The vintage work was priced below R20,000 ($1,100). Goldblatt’s work now routinely trades at upwards of R365,000 ($20,000) in the primary market, and regularly exceeds that value in the secondary market.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Death of George Floyd, 2020, inkjet print on Baryta paper Courtesy Goodman Gallery

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Death of George Floyd, 2020, inkjet print on Baryta paper Courtesy Goodman Gallery

Sustained demand for Goldblatt’s photos is a relatively new phenomenon. A 2009 exhibition of new prints from Goldblatt’s seminal essay In Boksburg (1982), hosted by Stevenson in Cape Town, generated not a single sale to a South African collector. “It is extraordinary, South Africans don’t have a clue,” Michael Stevenson told me at the time. Contrast this apathy with the R432,440 paid in November 2021 for a circa 2009 print depicting a group of white contestants in a beauty pageant photographed by Goldblatt at Boksburg Hypermarket in June 1980.

“I think a lot of it is a price perception,” remarked Stevenson in 2009 of the deep bias against photography among South African collectors. “How can a so-called edition be worth that amount of money? They are prejudiced to paper works in any realm, and then there is just the visual literacy. What has happened in photography in the last 20, 30 years internationally has gone past us and never been part of our realm.”

Attitudes seemed to shift in the 2010s. Well-established press photographers like Jodi Bieber, Santu Mofokeng and Guy Tillim forged viable gallery careers. Photographers Hasan and Husain Essop, Pieter Hugo, Mikhael Subotzky and Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko all clinched the Standard Bank Young Artist Award, an important early-career accolade. Muholi outpaced them all, becoming a bona fide global art superstar, particularly after the launch of their Somnyama Ngonyama series of darkly toned self-portraits in the mid-2010s.

Roger ballen, Threat, 2010

Roger ballen, Threat, 2010

And then the photo wave crashed. Marquee galleries no longer represent Bieber, Veleko and the Essop brothers. Muholi, who recently ended their long association with Stevenson, is now exploring sculpture and will present a social project – a connect-the-dots workbook aimed at children – at Expo Chicago in April, in association with Southern Guild.

Crash? Really! While trade in photography has hardly come to a standstill, and new talent continues to astonish, photography has experienced a noticeable downturn in perception and performance. A medium that only a handful of years ago seemed an assured calling card for South African artists looking to make a big splash, both at home and abroad, photography has noticeably spluttered.

Jurors of the Standard Bank Young Artist Award have shied away from artists working with photography. Collector interest has decisively coalesced around figure painting. Cinga Samson, a self-taught painter who studied photography at the Stellenbosch Academy and uses photography to orchestrate his fantastical portraits, far outsells Muholi by value.

The conspicuous pivot back to painting – a singular artefact that is alienated through its sale and cannot be re-editioned, only made anew – is perhaps best understood as the reassertion of an entrenched hierarchy. Painting is king, and photography is back where it has always been: on the margin, not quite mainstream, always emerging, always surprising, always due a revival.

Tatenda Chidora, Mask Conversation I, 2020, from the series 'If Covid Was A Colour', winner of Portrait of Humanity Volume 5

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory