Notes from a Curator's Journal

- by Nkhensani Mkhari

-------------

Jack Markovitz, Oysters in Midrand, 2023, R 26,000.00 ex. vat, CONTACT TO BUY

Introductory Rites

A decade ago, I stumbled into the city of Johannesburg, seeking what had been called the art scene. I moved to the city because I had this inkling that I’d be further from a traumatic childhood and closer to my dreams of being an artist. My dream came true. I’m an artist now. Albeit, I’ve heard, a reluctant one.

In the early days, the overall atmosphere surrounding the Johannesburg art scene was that of a mass, in the Catholic sense. A silent gathering, religious in its disposition. Strict. Seemingly impenetrable. Galleries like cathedrals and places of worship with the Artwork as the altar. Unattainable. Indecipherable. Clouded in myth and gravitas. Perhaps, except for the wealthy few who could afford it. At every opening, everyone would be so well dressed, composed, and put together. Arm in arm, flute in hand. In the early years, the clinical nature of the space(s) and extravagant objects had a way of making me feel hyper-visible yet so very small. I noticed how exhibitions had a clever way of turning the spaces, objects, and timelines we typically disregard into subjects of scrutiny and surveillance.

My naivety and ignorance were a gift in this case because I felt strongly that I could change things. Wide-eyed and with great enthusiasm, I started building. Today, I’ve worked for and with organisations in varying capacities from all the corners of the art world, both locally and around the world, including galleries, artist studios, art foundations, museums, biennials, triennials, art fairs, and academia, all while maintaining an art career. Alas, I wouldn’t advise anyone to try this. I almost died.

I view my career as a research process, an inversion of the working studio, researching the mediated process(es) inherent in the depiction and knowledge of culture(s) while examining the "Art world" as a locus of (re)production in the collective and individual psyche. Two of my key findings are: (a) Big ideas start in the arts; and (b) the art world is an organised mass. A crucible of paradox, purity codes, and prestige.

Liturgy of the Word

Let's rewind to 2021, when I was selected to be part of a curatorial residency hosted by the A4 Arts Foundation called Curatorial Connective. The Curatorial Connective was developed in response to the question, ‘How do we grow the critical middle between commerce and the academy?’ I came out of the residency enlightened, with new tools of observation and a keen awareness of the art world as an ‘infrastructure’, with every part playing a non-arbitrary role.

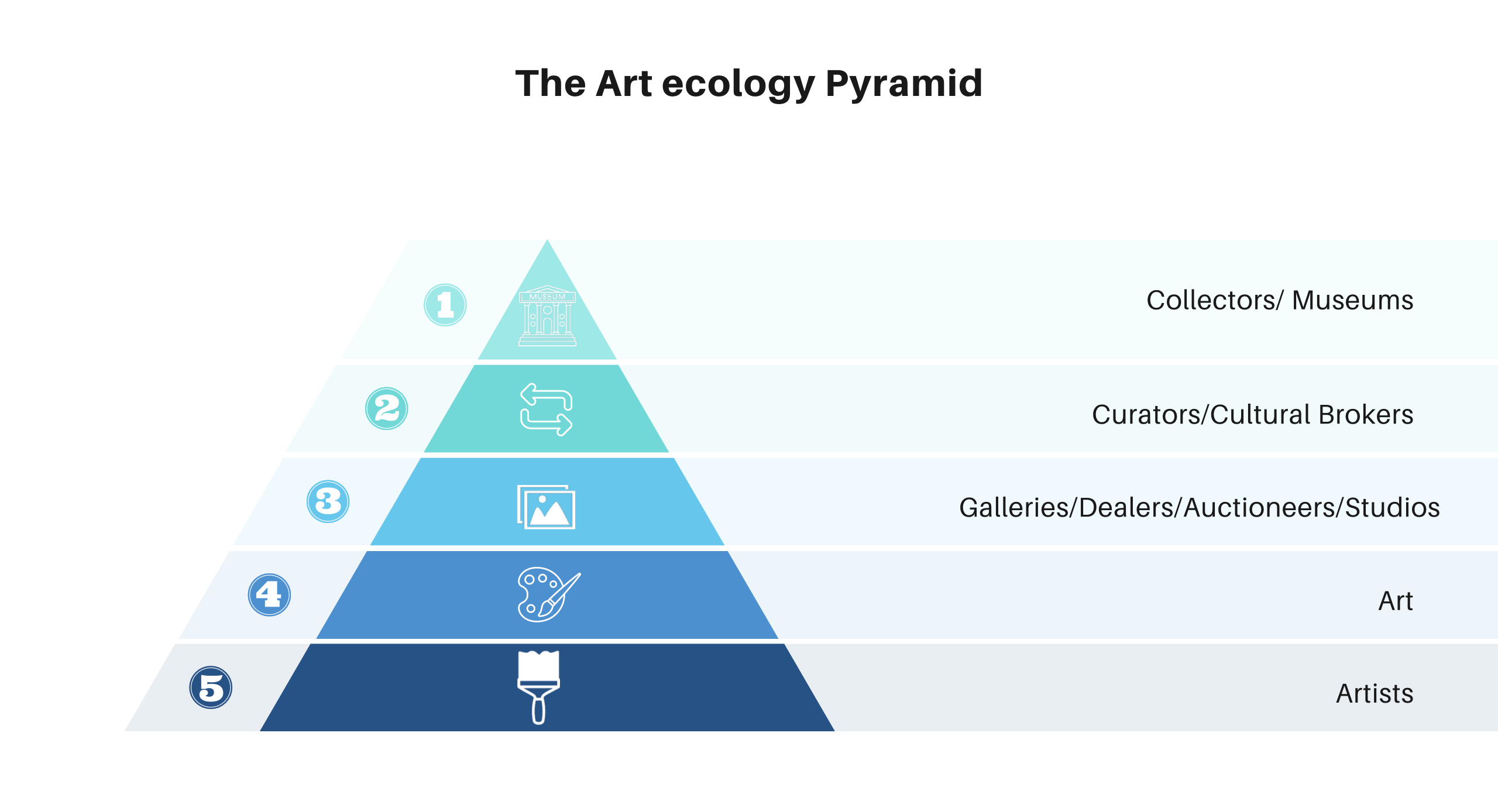

My interests rapidly shifted from making objects to the curatorial. Curation is more akin to architecture than art, as it’s a structural process. Curation can be the temporary modification of a structure or that which shapes the institutional body. The art world can be pictured as a pyramid (Figure 1). The key thing here is that artists are at the bottom of the pyramid. In this pyramid, terms such as "quality" and "value" have no obvious meaning if you think of the art world pyramid as a matrix of institutional and power relations because they are decided by labour divisions within the industry and created for a variety of reasons, including academic power and market value. The bottom line is that artists hold the art world up. At the apex of the pyramid are art collectors. In most cases, artists find themselves exchanging something permanent for something temporary; mediating this process is an unequal progressive-regressive exchange where both parties hold the subject-position.

As the collectors knowingly or unknowingly become custodians of the artist's work, archiving it, which is to say, collecting art, can be seen as the practise of preservation of something without inherent value, rendering it an act of faith. A potential accumulation of history in the hope that someone someday will listen or read. Our job, as the chosen few in the middle of the pyramid, is to make this transaction as equitable and frictionless as possible. I see this not just as an act of care but as one of radical moral courage. How do we make measured judgements of value today? First, we’d need to look at the whole pyramid instead of just one element, which is the art. From my perspective, we need to critique the whole infrastructure: collectors (museums), galleries, dealers, histories—everyone and everything must be implicated. To get to this place in an atmosphere of ideological parades, purity codes, and chicanery is a tremendous task, even for myself, but it’s time we invited complexity to the table. in an attempt to pinpoint the very instant of creation as such.

I believe the reluctance to disrupt consensus and attentively rigorous, sophisticated, discriminatory critique is the catch-22, the elephant in the room where there can be no art criticism without art history, and that of Johannesburg and South Africa in general is entangled with the decaying quagmire of apartheid, a labyrinth of colour lines, and the ongoing rupture that followed. In my experience living in this country, this is still a sensitive topic, an open wound. However, I strongly believe it makes fertile ground for a robust discourse around the state of the arts today; critique has to be connected and contextualised with that prior history in order to make vernacular sense, and that takes work. After all, the problem is that in the realm of contemporary art criticism, there is a strong fascination with the idea of evading judgment. However, critics who mistakenly equate mere description with judgment often deceive themselves about their true intentions to avoid passing judgment. South Africa seems to be stuck between what was and what could’ve been. Just as the old ones had to take a position to make a change, we need to take a position to evolve and grow. Art is change.

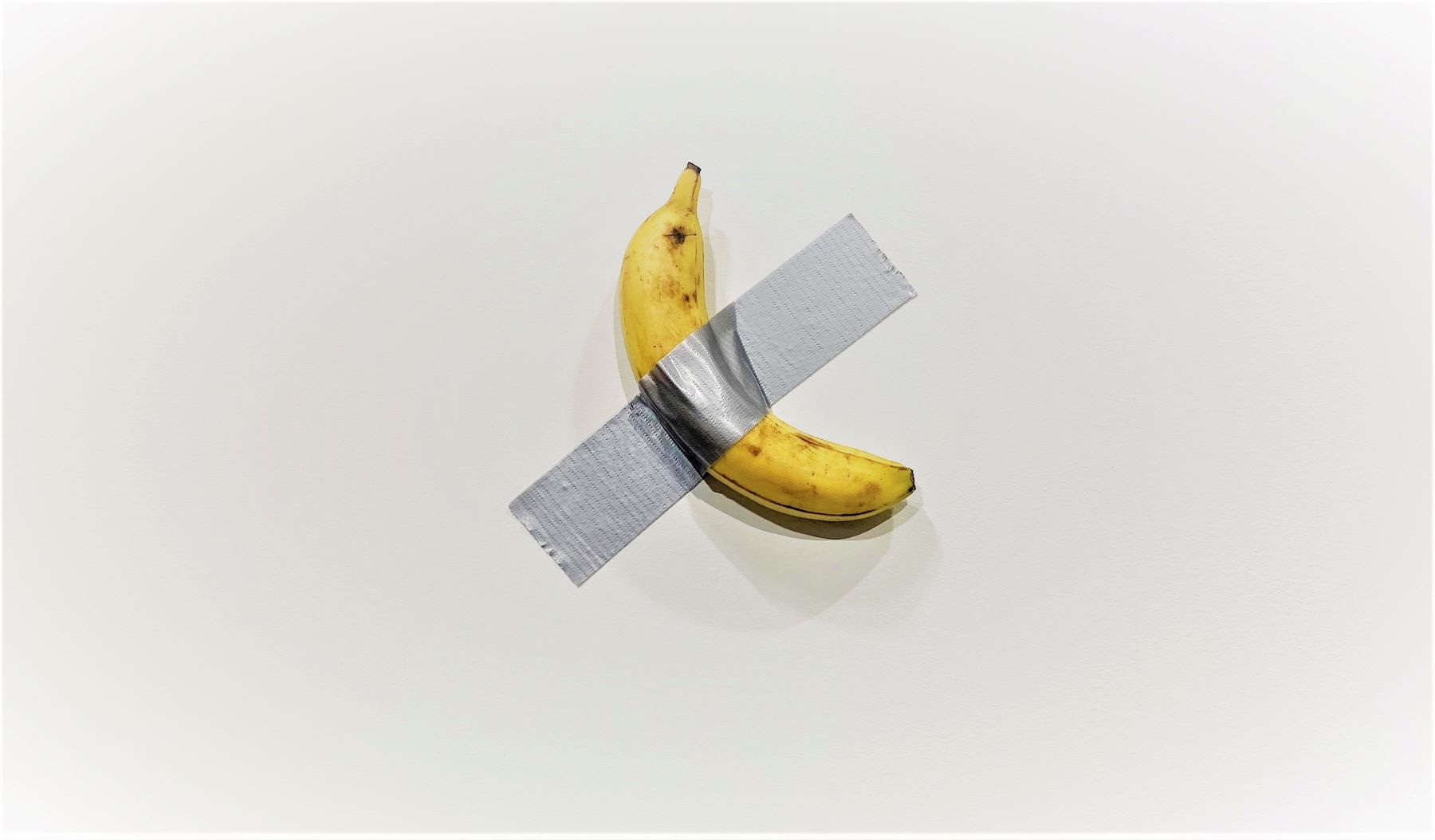

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, photo by Sarah Cascone, courtesy Artnet

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, photo by Sarah Cascone, courtesy Artnet

Liturgy of the Mass

You’ll notice in the pyramid (Figure 1) that there’s no art critic or academic. What happened to criticism is what happened to Biggie. No, but seriously, with the scourge of COVID-19 came a new way of doing things, the final nail in the proverbial coffin for the old guard. (I always thought Comedian, 2019 by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, was an omen.) Everything that happened after 2019 altered the whole hierarchical structure we came to know in a surreal and voluptuous way.

Independent artists took off to new heights, a la Nelson Makamo, Wonder Buhle, Banele Khoza, Talia Ramkilawan, Sthenjwa Luthuli, Phumulani Ntuli, Lunga Ntila, and countless unnamed artists - everybody is complaining about the prices but biting - project spaces, artist-run spaces and nomadic galleries like FEDE, Reservoir and Under Projects took off and continue to disrupt the ‘status-quo’, curators started asking questions surrounding the many unjustified opacities in the arts, black figuration had everyone in their feelings and pockets, we all started flying to Europe for shows without any local support, independent sections popped up at art fairs, marginalised groups and individuals - Ruangrupa, Lesley Loko, Sumayya Vally, Prof Dr Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung and Others - occupied key positions in the global art world renegotiating supplanted histories and disrupting established protocols. However beautiful all this is, we need to be wary. No reform can be implemented without facing the profound penalties of anachronism and historical naivety, which may result in regressive practices and ill-informed choices.

Art criticism needs to take the long past and the shifting present into consideration to formulate a contemporary criticism that takes position. Some of the latest examples of contemporary criticism on a global scale include Hannah Gadsby's exploration of Pablo Picasso's legacy in "It's Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby". The exhibition takes a critical, contemporary, and feminist approach while simultaneously recognising the transformative impact and enduring influence of his work. Prof. Dr. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung recently published an Essay aptly titled "Every Straw is a Straw Too Much," reflecting on the psychological burden of being racialised while doing art and the consequences thereof, highlighting the tragic story of Heiko Thandeka Ncube, a young Zimbabwean-German artist and educator who took his own life. His story serves as a reminder of the failures of the art-world, society and the urgent need to address racism and provide support for those affected by it. These are just two examples, both take a critical position in a moment of collective crisis.

In conclusion, art criticism is a translucent mantle, never settling but constantly floating within cultural conversations. It requires us to constantly reassess what art criticism can be, incorporate diverse perspectives, and embrace the monumental complexities of the art world. By doing so, we can ensure that art criticism remains a vital and transformative force, shaping the future of art and its discourse. We need to constantly ask, what else might art criticism be? - by Nkhensani Mkhari

Criticism cannot wait for the crisis to be over to have a "perspective" on the events. Criticism is more properly understood, in fact, as a cultural practise that is, in some deep sense, synonymous with crisis. Critical thinking is not just the act of judging or appraising. The critical moment is, as the OED reminds us, "the crisis or turning point of a disease," "of the nature of, or constituting a crisis. "The critical involves "suspense or grave fear as to the issue; attended with uncertainty or risk," while at the same time "tending to determine or decide," as in the decisive moment when a "critical mass" is achieved in a nuclear reactor. W.J.T. Mitchell 911: Criticism and Crisis

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory