Nigeria might be known for its photographic art but the medium has yet to be fully appreciated

- By Mary Corrigall

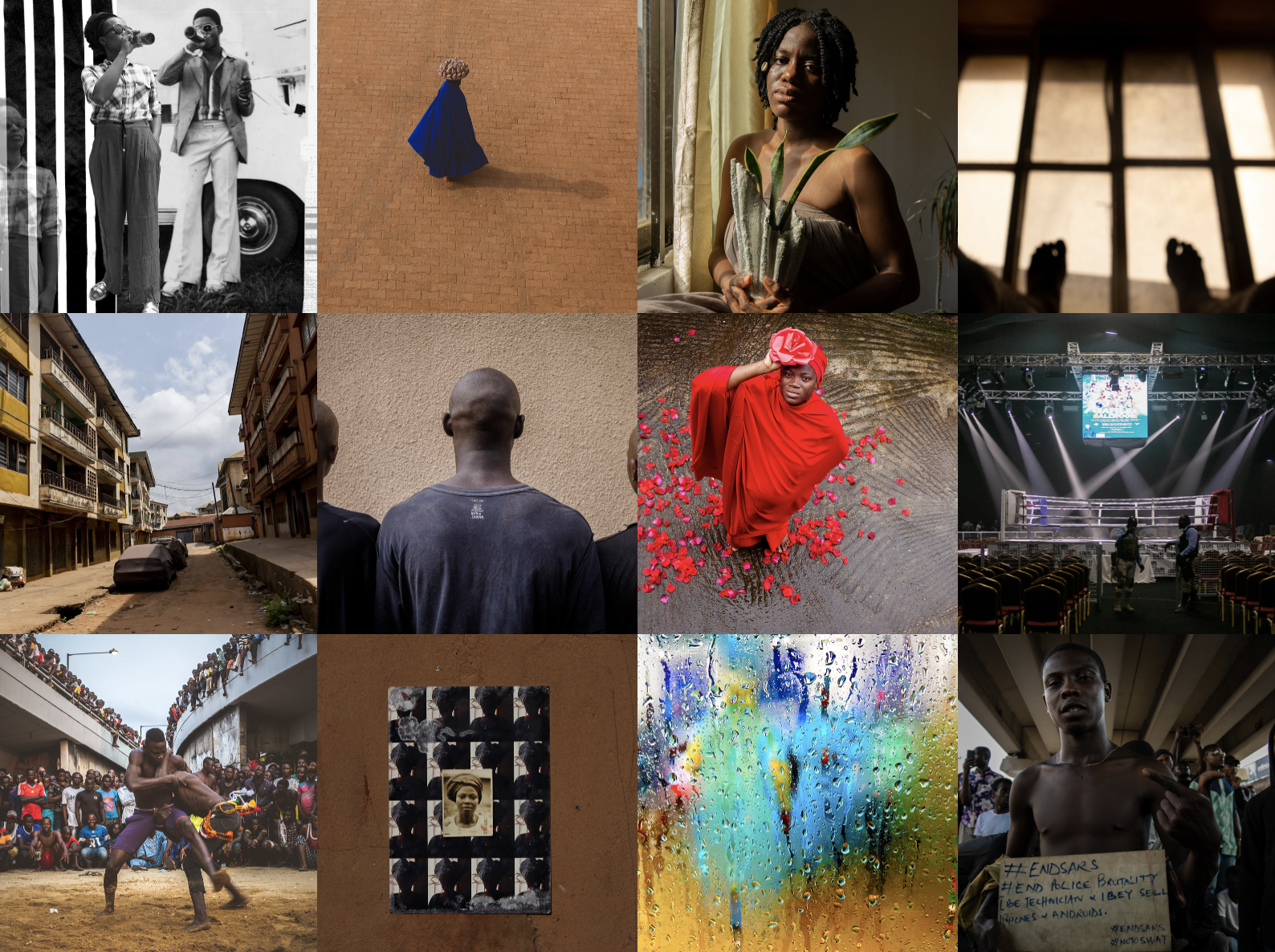

The Nlele Institute (TNI), featured photographs, image courtesy the Nlele Institute

Obásolá Bamigbola can pinpoint the place and time that he picked up a camera with purpose. This Lagos-based photographer had an affinity for image-making from a young age and when drawing and painting failed to satisfy, it was a camera that resonated with his artistic drive. However, it was when his maternal grandfather died in 2002 and the family travelled to his mother’s home town near Jebba for the funeral that Bambigbola sought out a camera. Hours from his mother’s home village, he knew of a large monument built in honour of Mungo Park, a Scottish explorer, set near the river Niger, which he was determined to visit. He walked there for hours on foot with his cousin in tow.

“So I thought myself I would not go to such a place without a camera. So I borrowed a friend's point-and-shoot film camera.”

The images that Bamigbola took of that historical setting, he claims were the first that set him on a course to become a documentary photographer. In Nigeria, however, the path to that endpoint wasn’t so easy to navigate in the absence of an institution that offers formal training for photographers. This forced Bamigbola and others like him to become autodidacts, which was also not without its complications given the dearth of books and information about photography. If Bamigbola had not received a package of seminal books on photography sent by an American photographer based in Canada (brought to Nigeria through a friend), it’s uncertain what his professional outlook might be at present.

The Nlele Institute (TNI) Founder/Director, Uche Okpa-Iroha presenting programs and projects of the institute during a conversation organized within the framework of the 12th Bamako Encounters, Mali 2019. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

The Nlele Institute (TNI) Founder/Director, Uche Okpa-Iroha presenting programs and projects of the institute during a conversation organized within the framework of the 12th Bamako Encounters, Mali 2019. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

“Those books opened my mind and changed my perspective as a photographer.”

This was around 2012, just over ten years ago and might well be the story behind many lens-based Nigerian artists and practitioners. This is despite the fact that Nigeria’s visual arts history and contemporary expression are strongly associated with the photographic medium. Think of Okwui Enwezor, the late Nigerian curator, who is often credited with opening up a rich discourse on contemporary African art in Western art capitals. His rise to fame and the assertion of African expression is rooted in the exhibitions he curated of photographic works by Nigerian and other African photographers. These include; In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present”, Guggenheim Museum, New York (1996), The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich (2001) and Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, International Center of Photography, New York (2006). These exhibitions and many others curated by Enwezor and others brought to wider attention the work of many Nigerian photographers such as Oladélé Bamgboye, Andrew Dosunmu, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Samuel Fosso and Iké Udé. In recent years through the efforts of other curators lens-based Nigerian artists such as George Osodi, Andrew Eisebo, Lakin Obubnwo and Akintunde Akinleye have also solidified their names outside their national borders. Many photographers and artists - such as ceramic South African artist Zizi Poswa - credit J.D. 'Okhai Ojeikere, known for documenting women's hairstyles as a leading figure of inspiration.

The Nlele Institute (TNI) Founder/Director, Uche Okpa-Iroha teaching at the Analogue Camera/Photography workshop. A collaborative workshop by CCA Lagos, The Nlele and Juliana Kasumu. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

Given this list of names – of which there are too many to mention – and the fact that Lagos is also home to the Lagos Photo Festival, staged in that city since 2014, it is surprising, if not a huge oversight that there has been no formal education offered for photography.

Fortunately, Uche Okpa-Iroha sought to remedy this dire situation by founding the Nlele Institute in 2013.

“His intention was to discover photography talents, develop them and deploy them into a global art scene,” says Bamigbola, who after undergoing a mentorship programme at Nlele Institute, now works for them as the head of special projects and programmes – when he is not busy producing bodies of works and images. Bamigbola has exhibited in Arles, France (2023), the Photo Biennale in Bamako, Mali and the Abuja International Photo Festival.

Members of the Nlele Institute (TNI) in Bamako, Mali during the 12th Bamako Encounters 2019. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

Bamigbola’s work has been circulated at the above-mentioned photo festivals and others due to the Nlele Institute’s objective to expose and present their graduates' work on multiple platforms.

This serves to draw attention to the Nlele graduates' work and supports the work of these various African-based photography platforms, which are not only meeting places for photographers from the continent but affirm the value of photography, which perhaps is not as valued as it could be on the African continent or in Nigeria.

In Nigeria, this is due to several factors. In the field of journalism, photographs have not historically been a prized part of the storytelling process, according to Bamigbola. Photographers that have done well in Nigeria have been those working for foreign news agencies such as AFP or Reuters or American publications, says Bamigbola. The financial stress on the media caused by the decline in demand for print journalism or news reports due to social media and the internet has had less impact on photographers in Nigeria when compared to South Africa or other regions. For this reason, Nigerian photographers have been motivated to look for opportunities beyond the local newsrooms, says Bamigbola.

The Nlele Institute exhibition prints production at the 13th Bamako Encounters in Mali, 2022. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

Exhibiting images in art galleries and other spaces and creating publications has become essential to photographers in light of the above but has its challenges in Nigeria. As has been the case in South Africa, art buyers are not always keen on acquiring photographic works – as they lean more towards traditional mediums such as painting, opting for one-offs, rather than editioned prints, even if they are cheaper. If you take a look at the artists selected to present work by the 10 galleries participating in this year's edition of Art X Lagos art fair, which has just taken place in Lagos, none are known for lens-based art.

This might not be a fair gauge of collector tastes in Nigeria – given this fair has shrunk in size and not all the galleries in that country participated in it – and it is also likely some of these galleries opted to present paintings to recoup the costs of taking part. Nevertheless, it does offer some idea of what kinds of works might be valued by Nigerian collectors.

Bamigbola says the uptake of photographers by galleries has been slow. However, Nlele has developed a good relationship with some galleries such as Rele, based in Lagos and Los Angeles in the US.

“They are beginning to accommodate photography in their space. Some of our members' work is part of the permanent collection at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Lagos,” observes Bamigbola.

He is optimistic as sales for some of the exhibitions staged by their members have been good.

“One of our members sold all her works on the opening night and another sold 40% of the works at the exhibition on the opening night,” recalls Bamigbola.

The Nlele Institute (TNI) Head of Programs and Projects, Obasola Bamigbola presenting TNI’s exhibition at BlaBla Bamako at the 13th Bamako Encounters, 2022. Image courtesy the Nlele Institute

Who or on what are young or new photographers in Nigeria training their lenses? There are always new trends, observes Bamigbola with a sigh of regret. He is of the school of thought that photographers should be guided by their knowledge and life experience rather than trends. However, he has observed that many newcomers to the scene are snapping images of religious festivals – of which Nigeria famously has many – and dominated by vibrant dress and performances lend themselves to compelling imagery – before that street photography was all the rage.

In many of these instances, the photographers have little knowledge or understanding of the communities that they are photographing – Bamigbola calls such photographers “tourists.” Photographers have to find their own voice and subject matter and immerse themselves in it, he advises. He has been photographing traditional practices of the Yoruba for three years now “as an insider.” Religious events offer only a small window into a wider picture, he suggests.

“The event is only a layer of the body of work. You have to understand the what, why, where and how,”

This is part of the journalistic practice that is taught at the Nlele Institute.

Photographing with a clear intention in mind should be an objective, urges Bamigbola.

The proliferation of photographic images that define our age, due to social media and cameras in cellphones - has heightened the value of this objective - the intentional image. Where once photographers spent more time getting their heads around the technology, advances in the tech have freed them up to take images with more purpose.

“Critical thinking is one of the most important skills for a photographer and that is what separates an artist from a hobbyist, critical thinking. You have to train your mind and shoot with purpose” says Bamigbola.

- Corrigall is a Cape Town-based art writer, researcher and consultant.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory