Joburgers are clamouring to see a trio of paintings

There are waiting lists to view a new exhibition at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation, which features works by three prominent female painters of the modernist era.

Is it possible to hold an exhibition with only three paintings? More importantly, can you drum up an audience without disappointing them? Surprisingly, a Joburg-based curator, Clive Kellner, director of the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation (JCAF), has managed to achieve both with the latest exhibition, Kahlo, Sher-Gil, Stern: Modernist Identities in the Global South.

--------------------------------------

Installation view of Part 3 Portraits and Self Portraits, showing Irma Stern, Watussi Woman in Red (1946). Courtesy private collection, South Africa. Photo Graham De Lacy

Kellner has relied on well-known artists to do so, but he has, through crafting a novel architectonic display, which sees all three works presented in their own mini-temples advanced a special mystique around them.

This is the third instalment of a series of exhibitions exploring and presenting art by female artists from the Global South. This exhibition should have been the first, as it draws from historical works by modernist artists who perhaps laid the foundations for the female artists that came after them, who have featured in the previous shows, Contemporary Female Identities in the Global South, and Liminal Identities in the Global South, which did feature some historical works from the 60s.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Frida Kahlo. Photo Graham De Lacy

However, opening a show with modernist works might not have aligned with the art foundation’s focus on contemporary art and a discourse on identity is perhaps not linear either. Bringing a Kahlo work to the country also proved to be a difficult and timely endeavour. There was some reluctance in loaning the work to a South African institution. If Kellner had not been persistent it would not be here. As such a survey show of Kahlo’s works would have been unlikely. Keeping an exhibition limited to three artworks had some practical considerations, though it is aligned with Kellner’s policy of ensuring considered engagement with art, which is pretty much guaranteed when there isn’t a room or rooms full of it to see.

Installation view of exhibition entrance. Photo Graham De Lacy

In this third show exploring, and indeed connecting female artists from the global South, sees Kellner dial back in time, identifying those artists who despite the odds and prejudice tied to their gender were able to carve out a place in the modernist art canon. Not that this is advanced as a condition that binds the female artists in this exhibition.

Undoubtedly, the three artists who are the focus of this exhibition are not overlooked, female artists. Of the three Kahlo is perhaps the most famous, perhaps due to figuring herself in her work and through this carving out a distinctive persona.

Installation view of Part 3 Portraits and Self Portraits, showing Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace (1940). Collection Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Nickolas Muray Collection of Modern Mexican Art. © Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Photo Graham De Lacy

As such, those who have booked a slot to view this exhibition, are perhaps drawn to seeing a Kahlo work in person – this is the first time this Mexican artist’s work is being shown in South Africa. The last time South Africans queued up to see an exhibition, was when the Picasso and Africa show toured the country beginning in 2005. The queues to view Kahlo, Sher-Gil, Stern: Modernist Identities in the Global South will be virtual – as you can only book timeslots to view online as only small groups are allowed in. So you won’t be bumping shoulders with anyone in the gallery. This is partly how Kellner has drummed up such enthusiasm for the show – if you limit numbers you drive up demand, especially in a city like Joburg where people clamour for any experience denied to them.

Installation view of Part 3 Portraits and Self Portraits. Photo Graham De Lacy

Of course, the second trick is to sustain suspense and interest in the viewer once they are there. This is where Kellner draws on his curatorial nous, in linking the three artworks and thus by the proxy the artists. Interestingly, the common thread that is foregrounded in the exhibition is not that they are women, but rather that they had an interest in depicting women, making portraits of them. For Kahlo, she opted for self-portraits, said to be related to her poor health, which kept her homebound but could have also been linked to her interest in crafting an identity. Stern wasn’t interested in depicting herself, which may be linked to insecurities she had about her body. "Irma doesn't depict herself because she's an abject woman to herself. It is through seeing the beauty of others. She projects her desires onto young black beautiful women,” observes Kellner.

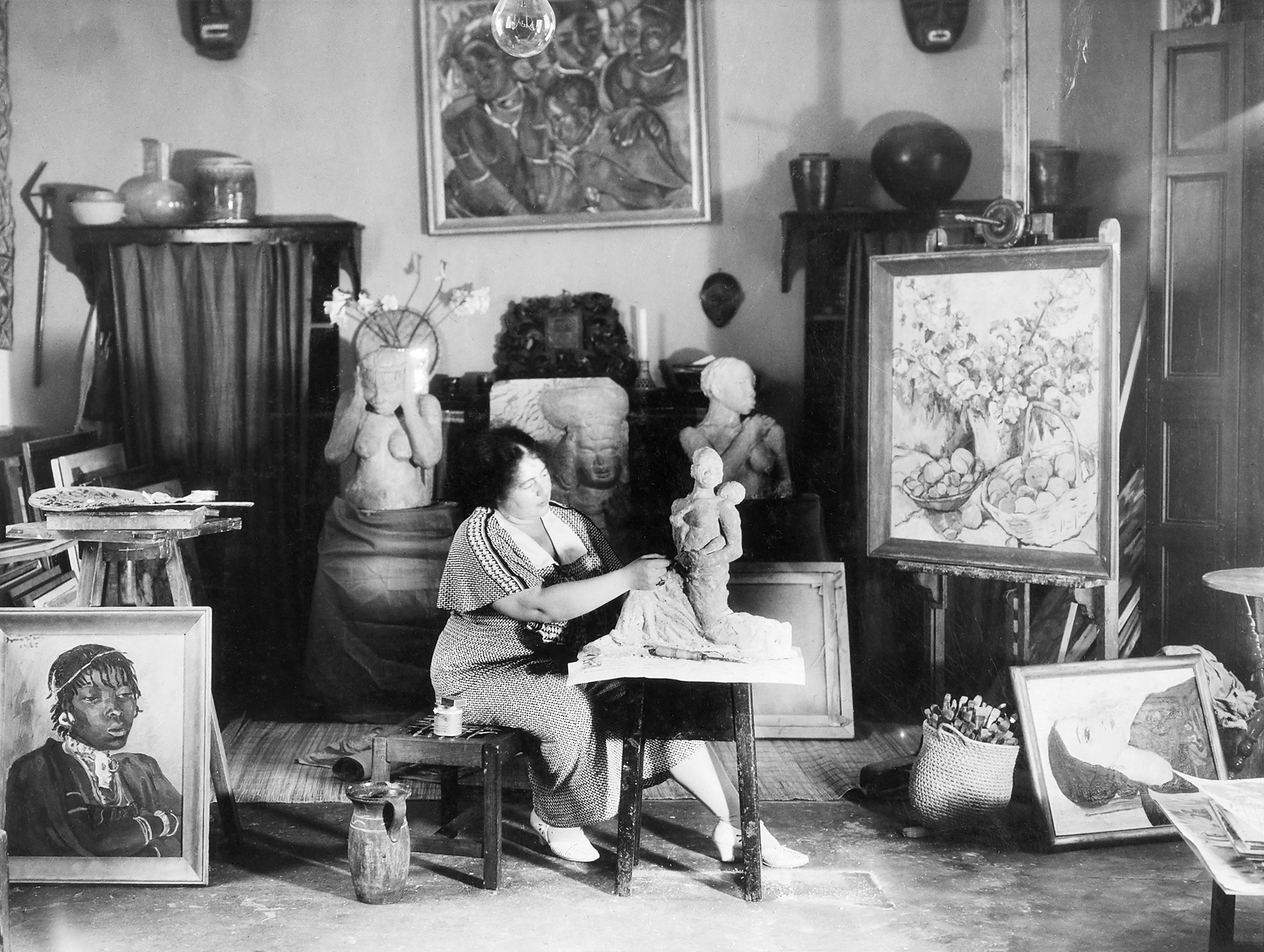

Irma Stern in her studio (1936). Courtesy National Library of South Africa, Cape Town (MSC31.5 Clippings, Folio 19)

As South Africans know well, she made portraits of friends and other people in her social circle and, more famously, of subjects she encountered during her travels in Africa – Zanzibar and the Congo. In Zanzibar, as an exhibition of her works at the Norval Art Foundation recently showed, her gaze wasn’t limited to women but extended to men too.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Irma Stern. Photo Graham De Lacy

In line with the exhibition’s focus on female subjects and thus a subtle interrogation of the nature of the female gaze, the Stern work, Watussi Woman in Red (1946) presents a woman in the then Belgium Congo in a flowing, bright red garment. It is tricky separating Stern’s anonymous portraits of African women from her fascination with the ‘exotic’ or a primitivist inclination, which her art education in Germany and alignment to German expressionism would have shaped. Indeed in the opening paragraph of her book Congo (1943) she wrote: “The Congo for me has always been the symbol of Africa. The sound Congo makes my blood dance with the thrill of exotic excitement. It sounds to me like distant native drums.”

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Amrita Sher-Gil with her paintings (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil reflected in the mirror), Paris, France (c. 1930). Silver gelatin print with selenium toning. Courtesy The Estate of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil and PHOTOINK

A central focus of this exhibition, which curiously begins in a room with large reproductions of three buildings that were significant in each of the artist’s lives, is to explore the visible but also invisible institutions (cultures) that shaped their practice, and or how they balanced divergent national identities and used their art to do so. For Stern, it is through her drive to capture the ‘exotic’ and perhaps find a sense of belonging that she arrives at an authentic language that is hers alone. It is rooted in Africa, via not only her vibrant palette, the energy of her painterly gestures and lines, which are defined by movement but in her expressive yet modernist language. In other words, in negotiating the line between Europe and Africa she finds her modernist language. This is the case for the two other artists in this exhibition, affirming the idea that the route to modernism is through 'getting in touch with indigenous' vocabularies in the global South.

Installation view of Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace (1940). Collection Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Nickolas Muray Collection of Modern Mexican Art. © Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Photo Graham De Lacy

In Kahlo’s case, as her portrait shows via obvious symbolism, she negotiates a catholic belief system with a desire to embrace her mestizo (Spanish and Indigenous mixed race) origins. With a German father and a Mestizo mother, she naturally had to reconcile with her mixed heritage. However, interestingly, some contemporary commentators believe she was of a privileged class and her use of Pre-Columbian cultural symbols in her dress and art doesn’t sit easily.

Kahlo has been accused of “glorifying a redefined past fabricated by co-opting and simplifying Indigenous cultures to render them palatable to a mestizo hegemony, while assimilating Indigenous people into a modern nation-state,” writes Joanna García Cherán, a Mexican commentator in an article for Hyperallgeric.

Installation view of Part 3 Portraits and Self Portraits, showing Amrita Sher-Gil, Three Girls (1935). Courtesy of National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. Photo Graham De Lacy

Sher-Gil also was the product of a mixed heritage, she was born in Budapest in 1913, to a Hungarian-Jewish mother and a Sikh aristocrat, who was a scholar of Persian and Sanskrit. Of the three, Sher-Gil is less known to South African audiences, though she has been hailed as “India’s Frida Kahlo” in the New York Times. Sher-Gil studies art in Paris, where she lived on and off but finds the spark for her art through her admiration for Indian classical art and Indian subjects.

“I realised my artistic mission then: to interpret the life of Indians and particularly of the poor Indians pictorially, to paint those silent images of infinite submission and patience, to depict their angular brown bodies,” wrote Sher-Gil.

Fritz Henle, Frida in Her Studio (1943). © and courtesy Fritz Henle Estate

This submissive behaviour she speaks of is very clearly articulated in the painting chosen for this exhibition, Three Girls (1935). The three subjects avert the viewers' gaze with their eyes fixated on the ground. They are crouched low as if demanding invisibility. Does Sher-Gil reclaim their subjectivity through her painting, in selecting them as subjects?

"You can't come with a New York feminist 80s agenda and then impose it on something in the past, it doesn't work," says Kellner.

Irma Stern in her studio (1946). Exhibition reproduction. Courtesy National Library of South Africa, Cape Town (MSC31.5 Clippings, Folio 19)

Three Girls, perhaps places young women who would normally escape attention at the centre, perhaps just as Stern, chose to depict black women, who would not have been viewed as 'valid' subjects for portraits, certainly in apartheid South Africa. Yet, did she see them as equals? Her white subjects were almost always named as opposed to the anonymous titles assigned to those subjects of colour. This will always present a barrier for South African viewers, though it hasn’t prevented her work from being appreciated at auctions or institutions.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Frida Kahlo. Photo Graham De Lacy. (L) Nickolas Muray, Frida with Idol (1939). Exhibition print. © and courtesy Nickolas Muray Photo Archives.

Through the presentation of the three works by the trio of artists, each hung in their own quasi-temples - box-like structures boasting architectural features from Mexico, India and Africa – Kellner asks his viewers to almost appreciate the works in isolation from each other and perhaps even the socio-political baggage we might attach to them now. Is this possible? Can we simply enjoy them for their artistic merit? The three works inspire many questions, relating to modernity, gender and privilege and, of course, identity – the core thread being teased out through the trio of exhibitions curated by Kellner. Are these questions particular to artists or audiences of the global South?

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Amrita at her easel Simla, India (1937). Silver gelatin print with selenium toning. Courtesy The Estate of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil and PHOTOINK

The last phase of this trio of exhibitions on female artists from the global South will be a journal with essays meditating on them. Perhaps the authors will present us with some answers. Or maybe more questions, as any exhibition worth attending should.

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town based art commentator, advisor and researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory