"I mean, why not music?" Uncovering the love affair between art and music

- by Sean O’Toole

------------------

Siemon Allen's advertisement for his 2009 exhibition Imaging South Africa - Records, Newspapers, Stamps at Bank Gallery, Durban

Siemon Allen's advertisement for his 2009 exhibition Imaging South Africa - Records, Newspapers, Stamps at Bank Gallery, Durban

Sound and music, two distinct auditory media, are currently enjoying prominence in some of Cape Town’s major institutions. The centrepiece of A4 Arts Foundation’s exhibition The Future Is Behind Us is James Webb’s masterful sound work Prayer (2000–), an astonishing archive of sound recordings of worshippers made in ten global cities over the past two decades. Across town, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa’s compelling survey of 200 figure-based paintings by 156 Black artists, When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, includes room-appropriate playlists curated by musician Neo Muyanga.

It is not just big institutions that are leaning into the potential of sound and music. Over the last two years, multimedia artist Mia Thom has presented a number of striking projects, notably at ABC Gallery and Everard Read, featuring her sculptures in conversation with music commissioned and performed by Mikhaila Smith and Lucy Strauss. Last year, Under Projects invited Fernando Damon, Vusumzi Nkomo and Rowan Smith, aka sound collective The Dead Symbols, to spend two days making sound and music. The ensemble filled the little gallery with their vast arsenal of analogue and digital instruments.

James Webb, Children of the Revolution, 2016

James Webb, Children of the Revolution, 2016

But for Muyanga’s music selection, which included familiar earworms by Miriam Makeba, Ebo Taylor, Youssou N’Dour and rap group NWA, none of these aural interventions would make an impact on Spotify Charts. That’s not the point or ambition of these projects, which harness sonic media in service of other ends. But for artist Siemon Allen’s astonishing research – visible online in his South African audio archive – or music writer’s Gwen Ansell’s supple writing about jazz, very little research and exhibition making has been devoted to this category of practice in South Africa.

Elsewhere, it’s a different story. Curators in resourced museums of the global north have explored the folds and overlaps of art and music. In 2007, Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art organised Sympathy for the Devil: Art and Rock and Roll Since 1967, an exhibition conceptually framed by Andy Warhol’s involvement with cult band The Velvet Underground. More recently, in 2015, Geniale Dilletanten [“Genial Dilletantes”], at Berlin’s Haus der Kunst, looked at the influence of seven 1980s German bands – among them the fabulous Einstürzende Neubauten, Die Tödliche Doris and Der Plan – on Teutonic art and culture of the period.

Jacob van Schalkwyk (right) reading a newspaper report as part of his performance Never Read the News Alone, with guitarist Dylan Graham (left) and artist Garth Erasmus (centre), David Krut Projects, Cape Town, November 2017

Jacob van Schalkwyk (right) reading a newspaper report as part of his performance Never Read the News Alone, with guitarist Dylan Graham (left) and artist Garth Erasmus (centre), David Krut Projects, Cape Town, November 2017

How would such an exhibition look in South Africa? One possible route would involve tracking the long love affair between artists and musicians. It is most consistently revealed in the packaging of music. Cape Town jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim often tapped artists to feature on the covers of his albums from the 1970s, when he still performed as Dollar Brand. They included Dumile Feni and Hargreaves Ntukwana. An earlier milestone here is Drum photographer Ranjith Kally’s striking cover image of faceless bus users for the Todd Matshikiza-composed jazz play Mkhumbane (1960). Kally’s migratory scene lays the groundwork for Moshekwa Langa’s moving short film Where Do I Begin (2001), which shows anonymous users boarding a public bus in the artist’s hometown of Bakenberg.

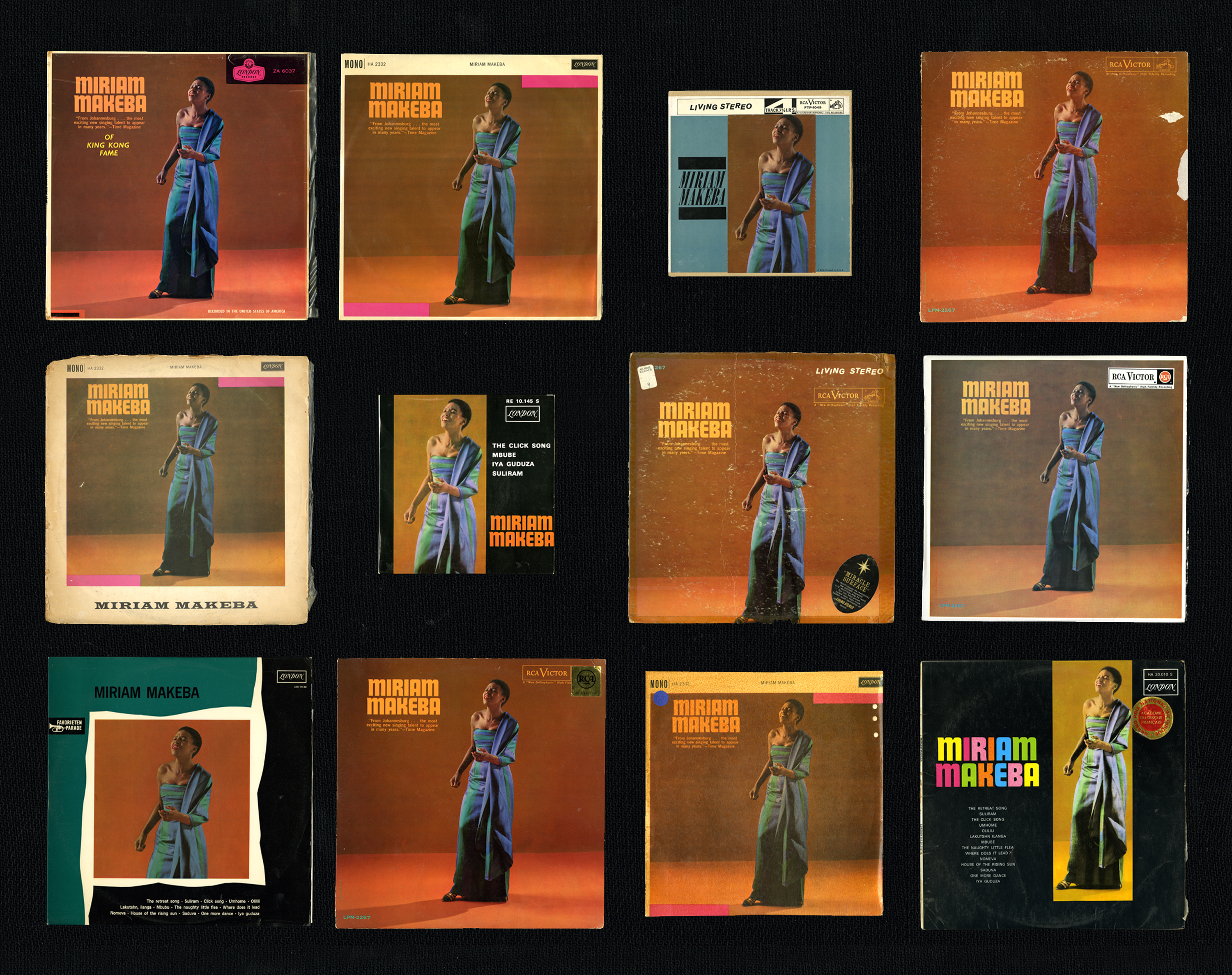

Siemon Alle, Labels from Makeba!, 2009, installation view at Bank Gallery, Durban

Siemon Alle, Labels from Makeba!, 2009, installation view at Bank Gallery, Durban

Album covers are a profitable terrain. Spoek Mathambo’s 2010 debut, Mshini Wam, featured one of Michael MacGarry’s fetish gun sculptures on the cover. Photographer Pieter Hugo directed the video for Mathambo’s single Control from the same album. And then there’s Norman Catherine cover illustration for bassist and composer Carlo Mombelli’s album I’ll Press my Spine to the Ground (2016) and Nandipha Mntambo’s image on the cover of the Blk Jks’s 2021 concept record Abantu/ Before Humans. Zanele Muholi photographed LGBT-icon Desire Marea for their debut album, simply titled Desire (2021). And just for the sake of being up-to-date, jazz drummer Tumi Mogorosi’s new album, Group Theory: Black Music (2022), has Andrew Tshabangu’s 2001 photo of a group of Venda dancers on the cover.

Mia Thom's sound sculpture from her 2021 exhibition Night Swim, an immersive exhibition made in collaboration with Lucy Strauss and Clare Patrick at ABC Gallery, Cape Town

Listening to Mogorosi talk with Nkomo at Under Projects about the genre-hopping references underpinning his album, I was reminded of how often artists also make music. Zulu Bidi, who played bass in important 1970s jazz band Batsumi, was also an artist. His work illustrates a handful of albums from the era. Bidi was a renaissance figure. In 1978, together with David Koloane and Hugh Nolutshungu, he opened The Gallery, Johannesburg’s first black-owned art gallery, at 280 Main Street.

The 1980s saw a number of white artists devote their spare time to making music, among them Willie Saayman of Khaki Monitor and Neil Goedhals and Kendell Geers of Koos. In the 1990s, James Webb led a band called Severed Head Scream. “I sang and used allot of effects on my voice,” Webb once told me. “After the break up of the band, I became interested in using sound to create atmosphere in theatre.” And so his career with sound developed.

Jacob van Schalkwyk, Wonky Nights, 2022, oil on canvas, 450x450mm

Jacob van Schalkwyk, Wonky Nights, 2022, oil on canvas, 450x450mm

It is now little remembered that Ashleigh Mclean, an artist turned curator with Whatiftheworld Gallery, briefly fronted a rockabilly band in the early 2000s. Photographer Guy Tillim has played in two bands, Wrongman and Vermaaklikheid Bakkery Orkes, the latter with journalist Rian Malan. Writers and artists frequently collaborate. Neo-pop artist Jacques Coetzer makes music with journalist Fred de Vries as The Silver Linings. And by way of a declaration, I should say that I have made two albums with painter Zander Blom. We are called The Bad Reviews.

Dead Symbols, a band composed of Vusumzi Nkomo, Fernando Damon and Rowan Smith, performing at Cape Town's Under Projects, October 2022

But why music? I could try answer that question myself, but instead I reached out to sculptor Rowan Smith and painter Jaco van Schalkwyk.

“I mean, why not music?” responds Smith, who in 2012 translated the sound of a guitar smashing into a piece for solo piano with artist and composer Yun Ingrid Lee. Smith’s many exhibitions over the last decade have materialised his deep enthusiasm for all things aural. “I think music-sound is a fascinating mode of research or inquiry that allows for all sorts of different constraints and parameters within which to work in comparison to the plastic or visual arts.”

James Webb, Wa, 2003, performance still for YDEsire

James Webb, Wa, 2003, performance still for YDEsire

Like Smith, Van Schalkwyk is also a serial collaborator. “I don’t go around town calling myself a musician so music doesn’t really sit on my CV,” he says. “But I’ve played some incredible shows so I have great stories.” They include performances with artists Garth Erasmus (a saxophonist who also plays self-made instruments) and Dylan Graham (guitar) in the ensemble NRNA (Never Read the News Alone) in 2017.Van Schalkwyk also collaborated with Blom. Their noise act Jaco + Z-Dog even did a gig at Blank Projects in 2011.

Rowan Smith's bronze Space Age Pop (2009) on view in Twenty, South African Sculpture at Nirox Sculpture Park, 2010

Rowan Smith's bronze Space Age Pop (2009) on view in Twenty, South African Sculpture at Nirox Sculpture Park, 2010

“Music taught me about other people’s stories and that those stories could become my own,” says Van Schalkwyk. “I feel like my understanding of the world is based on the music I’ve made with other people. It has completely changed my life over and over again.” Music will doubtlessly continue to change lives, this as future generations of artists look to music and sound, consanguineous media that are defiantly ephemeral, temporal and invisible.

Sean O’Toole is a writer, editor, curator and terrible singer based in Cape Town

Mia Thom, Attune, 2021, found double-bass case, harp case, speakers

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory