How has technology advanced art collecting?

AI and the digitisation of art marketing have impacted art production and dealing, how have collectors benefitted?

---------------------------

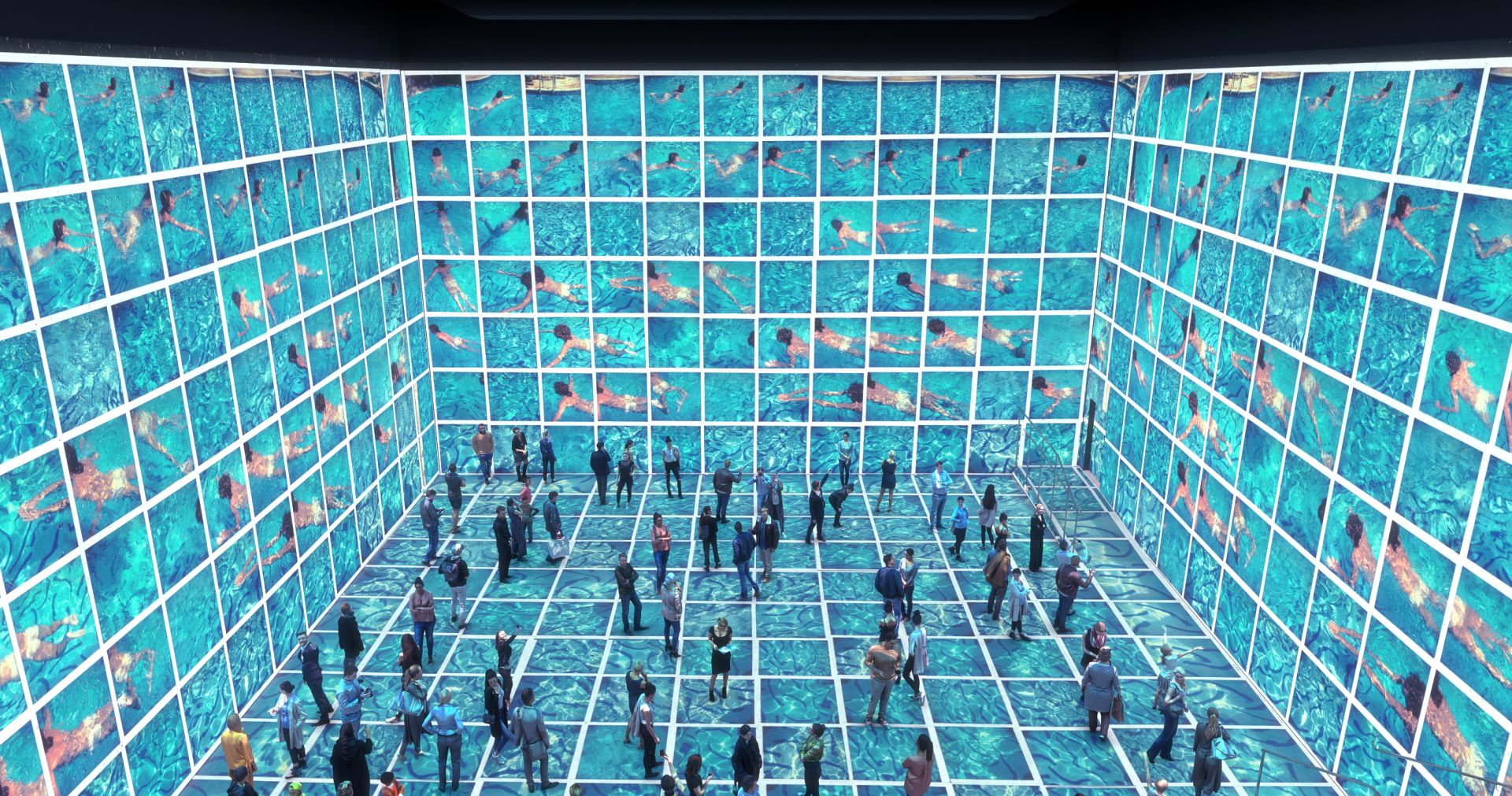

Installation of David Hockney’s ‘Gregory Swimming Los Angeles March 31st 1982’, composite polaroid, 27 3/4 x 51 1/4". (Image credit: © David Hockney)

Installation of David Hockney’s ‘Gregory Swimming Los Angeles March 31st 1982’, composite polaroid, 27 3/4 x 51 1/4". (Image credit: © David Hockney)

The impact of recent developments in AI on traditional art-making has been dominating discussions, given the recent prominence of AI image-making software using text prompts or images to generate digital art. Before that, during Covid-19 the rise of the NFT art and its impact on the traditional art market was the focus and fed speculation in digital art collecting.

Little attention has been paid to the manner in which technology has shifted art collecting, for ultimately it has not only popularised, democratised art buying and diversified taste in art but also has formalised art collecting in unprecedented ways. It has also, as is always the case with overeager techies, led to a glut of superfluous APPs, software and businesses that have added little if any value to art collecting.

Before Covid-19 and the impact it had on the digitisation of art marketing, many art dealers claimed that many of the artworks sold at art fairs found buyers via Whatsapp and/or PDF catalogues. As such, art fairs appeared to be the catalyst for sales rather than necessarily the essential physical platform to generate sales, though you could argue that many of those dealers first cemented relationships with such buyers in person. Nevertheless, this points to the fact that collectors can access artworks and acquire them from the comfort of their sofas.

©2022 Banco de México. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, Courtsey Mexican Geniuses Exhibition, @brainhuntermx

The recent 2022 Art Basel, UBS Survey of Global Collecting substantiated the role of various technologies in the art buying process. It was found that 60% of the High Net Worth (HNW) collectors surveyed for the report had purchased an artwork using either an email or phone call to the dealer only (without seeing the work in person). While the study affirmed that the majority of HNW collectors preferred buying directly from dealers, the fact that 53% of them acquired works via Instagram and Third-Party platforms (think of Artsy or Latitudes Online) affirmed the way in which digital innovation has shifted buying patterns and disrupted traditional models. In addition, 59% of HNWs indicated that they were buying art from NFT market places – Open Sea, Rarity etc. In other words, not only is digital innovation shifting where and how collectors acquire works but they are investing in digital art - despite the implosion of crypto currencies and its knock-on effect on the value of NFTs.

Undoubtedly, Covid-19 had a massive impact on art collectors' behaviour and willingness to acquire art virtually either through OVRs (online viewing rooms), third-party platforms or social media. However, technology has been facilitating art collecting for some time – perhaps since the internet was established, making it possible for collectors to acquire artworks from all over the world, which has 'internationalised' taste in art and, of course, compare prices.

Not that acquisitions are driven by price comparisons, however, the availability of auction records has made it possible for collectors to have some idea of the resale value of contemporary works they may be considering purchasing. Of course, this is only possible with mostly well-established artists – though emerging artists are finding their way onto auctions, particularly in South Africa and some of the French-based African sales, where the value of emerging artists is being tested and solidified at auction.

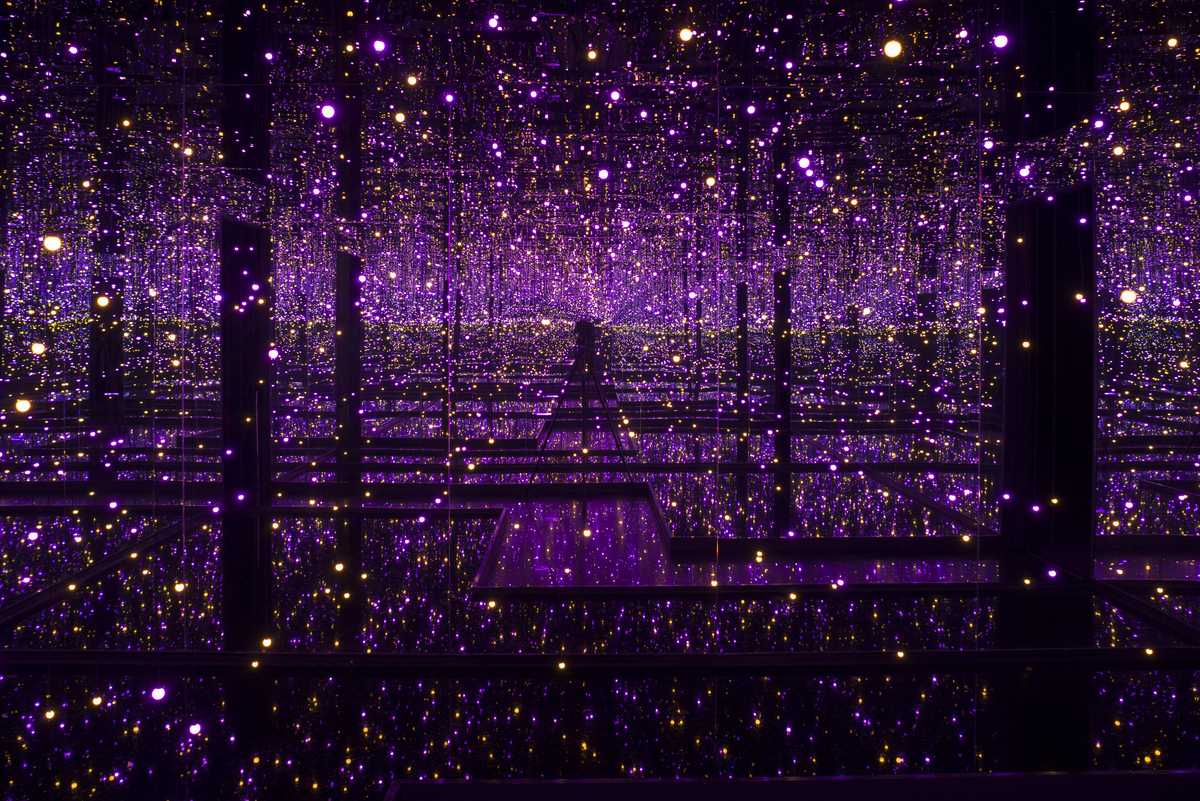

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room - Filled with the Brilliance of Life 2011/2017 Tate Presented by the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro 2015, accessioned 2019 © YAYOI KUSAMA

Comparing and finding auction records can be tedious and time-consuming, however, given how many auction houses exist and auctions take place. In addressing this problem, there are many online businesses dedicated to aggregating all the auction records such as Art Price, Mutual Art and Art Net. Most of these websites naturally charge a fee, or you can gain access for a limited period. What is particularly useful for collectors is not only being able to track all the international auction records set by an artist but if you are hunting for a work by a specific artist you can set an alert that will notify you if any of their works come to auction.

Setting this kind of alert can also serve as an indicator as to how frequently their works are being auctioned – this often indicates that their works are desirable, though conversely, it could also mean that collectors are keen to ‘offload’ them – while they still have significant value. As these tools have been developed by US-based companies – they tend to mostly aggregate data from the major auction houses in the world. As such, records set by smaller auction houses in Africa don’t always filter into these databases.

Another substantial technological development that benefits collectors is the variety of software available to archive and catalogue their collections. Such tools – offered by Artlogic, Art Galleria, My Art Collection - allow collectors to capture all the details about the artworks. Aside from the dimensions, mediums, you can also list other relevant information on them such as the location (they could be in different storage units), the purchase details, insurance values, condition, and provenance.

Once you have loaded your entire collection to any of these portals, you are more or less locked into them, however, as it would be time-consuming to load a collection elsewhere. Some of these tools are expensive with a monthly fee of £60 (R1245) to $200 (R3400). In my opinion and experience with clients, creating an inventory of a collection in an Excel document is the most economical and best long-term solution. You can update currency exchange rates in Excel as well as do an analysis of the collection. The main benefit of the software collection management options is being able to quickly share information on an artwork with someone else – instead of manually transferring the information from an Excel document to a PDF one. In this way, the software management tools are perhaps best suited to those collectors who are constantly selling works. This is probably why most of the collection management software is targeted at galleries, dealers or artists – as they are geared toward selling and sharing information and tracking interest in works.

In our drive to digitise everything and allow technology to do the work of humans – there are naturally some APPs out there that are designed to replace the work of an art adviser. Such as Limna, which supposedly can draw from its database of records to determine whether a dealer is offering a good price for an artwork or give you an estimate for an artwork you might want to sell. On paper, this AI-driven technology sounds brilliant. In reality, it simply doesn’t work. For starters, there is no comprehensive database with prices in the primary art market (offered by galleries or dealers) and dimensions are sadly not the main characteristics that determine the price.

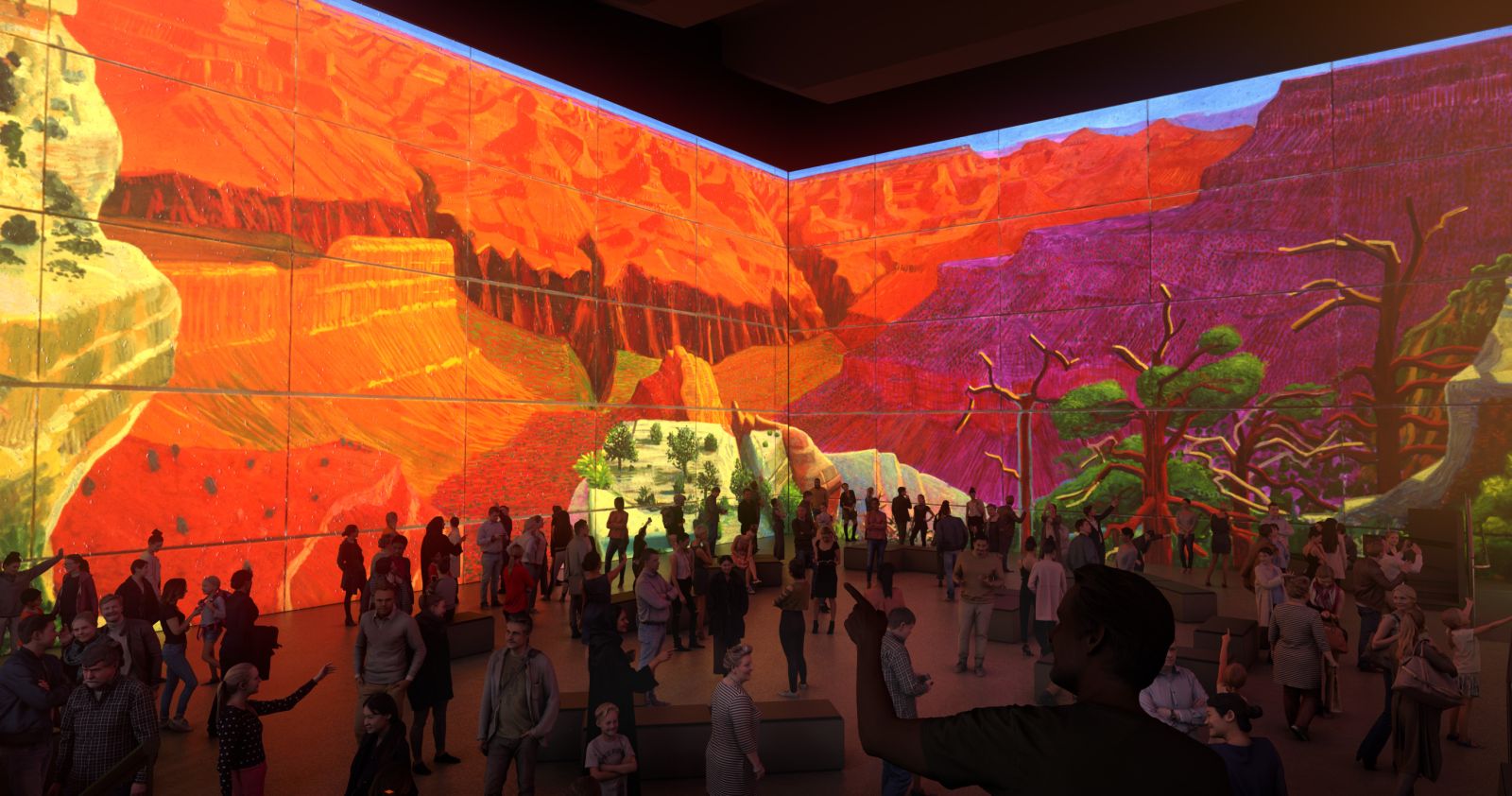

Installation of David Hockney’s A Bigger Grand Canyon, 1998. Oil on 60 canvases, 81 1/2 x 293" overall. (Image credit: © David Hockney Collection National Gallery of Australia, Canberra)

Installation of David Hockney’s A Bigger Grand Canyon, 1998. Oil on 60 canvases, 81 1/2 x 293" overall. (Image credit: © David Hockney Collection National Gallery of Australia, Canberra)

Technology designed to virtually place artworks in a room and see how they look is pretty useful for collectors in advance of buying or work or perhaps to rehang works in their homes or offices. Art Placer is one such website offering this service. You load your collection or the works you are looking to ‘hang’ and you can opt to do so in an image of the room or in a gallery where you can change the wall colours. You need to take a high-quality, clean image of a room to exploit the technology and unfortunately, you can’t plug in the dimensions of the room or wall space. So the technology falls a little short, but it is helpful in curating artworks – seeing what they look like side by side and which wall colours would work best or for generating an online exhibition.

Ultimately, however, blockchain technology is probably the most significant development in the art collecting world, providing a secure, transparent, and decentralised way to authenticate, track, and transfer ownership of artworks.

This naturally, relies on creating a digital certificate of authenticity for a physical or digital copy of the artwork. This will help eliminate fraud and allow for more transparency for buyers around the provenance of the artworks. It would require people to digitise their (physical) art collection via a platform that can supply certificates.

Cumulatively, all these new technologies have repositioned them in the larger art landscape. In being able to access and share information about their collections they have become more powerful players in the art ecosystem. This has led many into dealing art on the sidelines or permitted others to openly champion artists to shore up the value of their collections. Direct access to the public via social media, newsletters, and websites has also allowed collectors to carve out their own art personas, position their collections or accrue more social status.

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town based art commentator, advisor and independent researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory