FOUR CRUCIBLES: ON JANE ALEXANDER, WILLEM BOSHOFF, ED YOUNG, AND JAKE MICHAEL SINGER

By Ashraf Jamal

This feature was originally published on ArtThrob

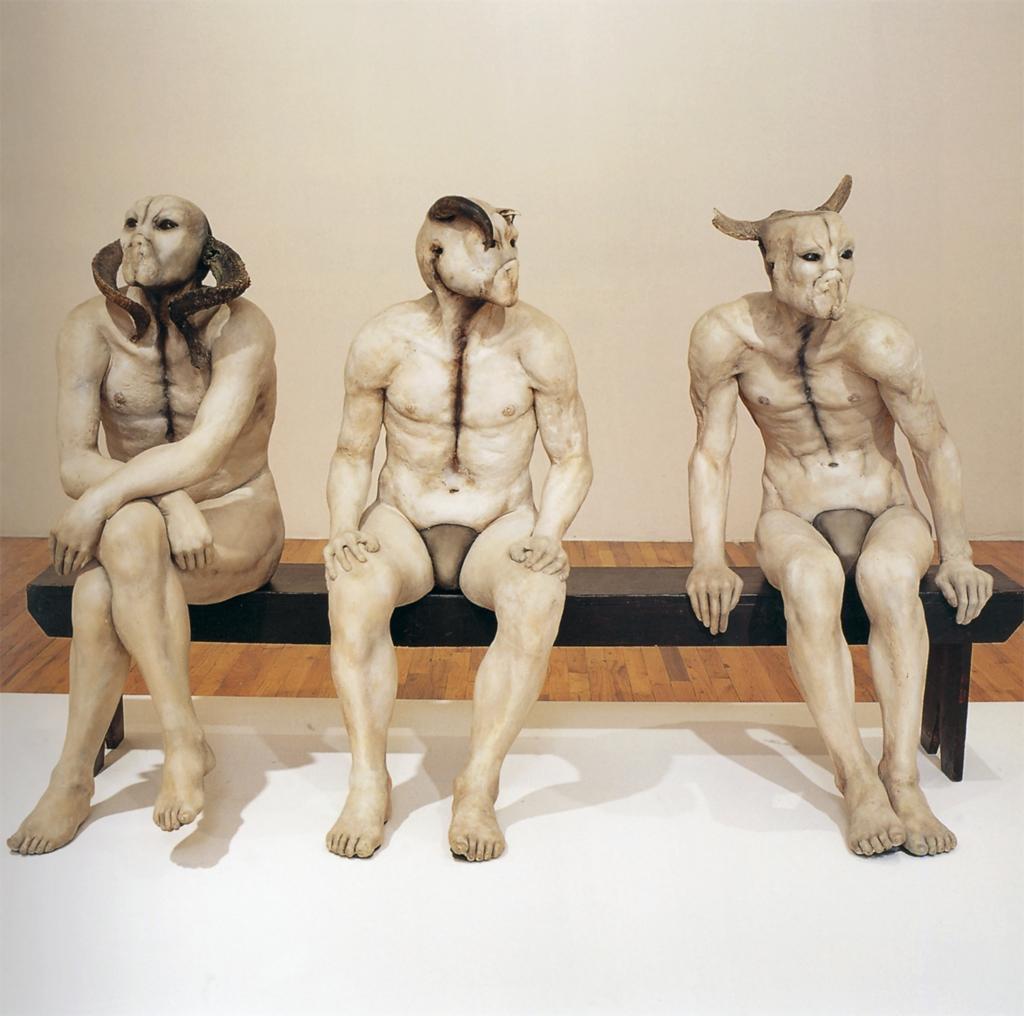

1986. For her Masters in Fine Arts at Wits University Jane Alexander presents Butcher Boys. I try topicture her examiners. What are they discussing, seeing? The country is in flames, yet there they sit, the examiners, the boys. Do they hear Winnie Mandela’s cry, ‘Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this land’?

I doubt there ever was a moment in the South African art academy more loaded. If Alexander is our most celebrated artist – notwithstanding the hype around William Kentridge or Zanele Muholi – it is because Alexander, more than any other, entered our bloodstream. She is the toxin in our blood supply – our ‘forever chemical’.

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys, 1986. Plaster, paint, bone, horns, wooden bench, life-size.

‘There … in the National Gallery … they wait’, Mike Nicol writes in The Waiting Country (1995). ‘Their faces are distorted as the skin has started to decay. Their mouths have disappeared. But their eyes have enlarged: gone huge, brown, glassy from looking always in the distance. In places their spines have broken through the flesh; you can see the plates of their skulls. They have grown horns’.

For Nicol, The Butcher Boys are our ‘Maleficents’. ‘They have shadowed our lives constantly …demanding more and more blood. It is now mayhem they want’.

Dread, uncertainty, terror, are the epithets we attach to the hell those boys convey. They been benched for decades, watched our every misstep. Mute as they are – ‘their mouths have disappeared’ – is it them, or us, who are the doomsayers? Are they waiting, waiting, without judgement?

The Butcher Boys are a hydra-sphinx. They stake no claim upon us, not even the dread they inspire.

They harbour no ill, want for nothing, neither blood nor mayhem, and yet, in our desperate urge to find a source for all our ills, it is to them that we ascribe all our sleepless gnashings.

It is unfashionable to speak of the inscrutability of art. The Butcher Boys must be doing and saying something. They are not. They are an allegory. That their ‘huge’ eyes draw us thither, is but one of many facets that account for their riddling power.

History is only episodic for those who imagine that life has consequence, that answers patiently await those who pose sound questions. But what if Reason is null? What then? Where does one go to find the answers one seeks?

***

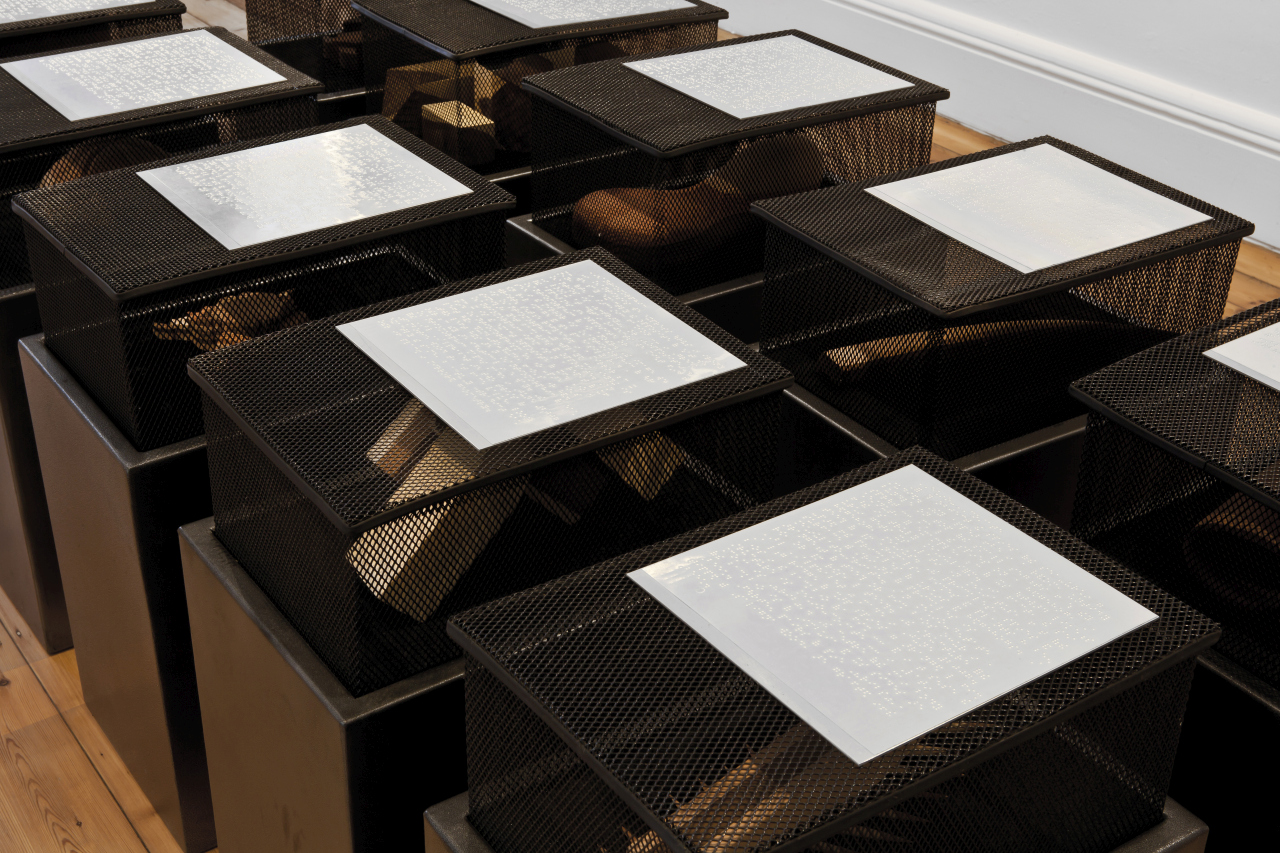

1995. I am speaking with Willem Boshoff at his home in Johannesburg. He has a beautiful and dark mind. The sculptures he is making – one a day, every day of the year – are modest forms in wood. It is not what they look like, what they physically express, that matters most, but the words etched in braille on metal sheets. The sheets are clamped to black boxes which contain the wooden sculptures. You can only see them, poorly, through a perforated lattice. Sighting is the problem. This is not a work made for eyes. The title of the work is Blind Alphabet, its purpose to force us to rethink what we see, or think we’re looking at. They can be understood – if understanding matters most – only by those who can decipher Braille.

Willem Boshoff, Blind Alphabet, 2007. Wood, wire, aluminium Braille, cloth, steel, 72 x 35 x 50.5cm (each)

The boxes can be entertained individually, but the greater impact occurs when seen en masse. They remind one of tombstones, a mass commemorative grave. There is something chillingly funereal about the modular and serialised whole. These are not Le Corbusier’s machines for living, they are machines for dying. Or rather, machines that house the dead. The source for all Boshoff’s words is Latin, a tongue for silence.

If Alexander’s Butcher Boys is a riddle that echoes our agony, doubt, fear, vengeance, self-hate, bloodlust – the high-drama that comes with violence, never slaked, always unrequited, because it comes from bitterness – then the riddle which Boshoff presents to us concerns blindness – our damaged cortex, our inability to apprehend what cannot be seen.

Is he, Boshoff, the one-eyed king in the land of the blind? Is he asking us to develop different and better interpretive skills? Is he telling us that Reason will not help us, that hermeneutics – the business of interpretation – always comes to naught? That what we need is ‘Blindsight’ – the ability to navigate a meaningless world with the aid of all our other neglected senses and intuitions?

Is art not about looking at all? Boshoff muses: ‘The skin is the largest organ of the body. If we as humans did not have eyes, we might have been, like earthworms, completely dependent on our skins to establish where we are, what we know, and how to move around’.

Must we become sensate? Is intuition and feeling our last resort? Is that why ‘immersive art’ is so popular, so menacing, so fun? Is that why we have quit our minds, become mindless? And is this the danger that Boshoff foresaw?

***

2010. 2019. Two sculptures by Ed Young, the first consumed by manic glee, the second a station at the cross. The first is Arch, a sculpture of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, airborne, flying across a ballroom ceiling hands firmly clasped to a chandelier, eyes and mouth beaming, purple robe aflutter. The second is Hero, a hyper-real copy of the artist as Superman. He is standing at a ledge, hands cupped to a pack of Marlboro and a lighter, his cape buoyed by the Southeaster, the ‘Cape Doctor’. Melancholy consumes our hero. Or is he just pissed off because he can’t get the light to start?

In the space of nine years we witness a crash. These figures sum up our bipolarity, our mania and frustration, our hope and its bankruptcy. Nothing is given, or not given for long. If the darkness that consumes our hero seems banal, it is because of the extent of our enervation. We play dress-up badly.

We can neither countenance our deepest dread, nor sustain our hopes. As for mind? Reason? It is doomed.

Ed Young, HERO, 2019. Silicone paint cotton rubber and hair, 3 x 11m. Image: Nina Lieska

Arch and Hero are the bookends of our present and recent past. They tell us of our cavorting and our impasse, our faux joys and acute sense of damnation. Our arrested history. A wall text accompanies Young’s Arch: BE PATIENT WE ONLY HAVE A FEW THINGS TO FIX. But alas the problems are now legion, and Superman is not capable of fixing any of them.

***

2019. And something far more promising is also afoot. Jake Michael Singer’s Dawn Chorus. This astonishing sculpture possesses none of the dread we assign to Alexander’s sculpture, the frustrated and frustrating challenges posed by Boshoff’s Blind Alphabet, nor the manic-depressive flip captured in Young’s mood swing. This fourth sculptor, Singer, is neither interested in an air show nor being grounded. He cares not a jot for our misery or impaired minds and eyes. Not even Yves Klein’s leap into the void interests him. Instead, with the daring and risk one mistakenly assigns to youth, Singer chooses to leap into the infinite.

A ‘dawn chorus’ suggests a profound awakening, a song sung by many, but what we see is a single figure – an archangel? – as it twists about its core, impelled by a force far greater than history. No fear will stop its boundless flight, no doubt, no pain.

Jake Michael Singer, Dawn Chorus, 2019. Marine grade stainless steel, 280 x 140 x 160 cm.

If history hurts, and if this is the burden which Alexander, Boshoff, and Young carry, then Singer has miraculously sloughed its shackling weight. Like a rocket, jettisoning all baggage and needless fuel, Singer’s chorus tears through our atmosphere and pierces the realm of the gods.

It is not only liberty from a secular world that Singer seeks, he also seeks to free himself from a vengeful God before whom he is unwilling to kneel. Neither terra firma nor an imagined Absolute will shackle him. He knows no gravity and seeks no redemption. Something else, far greater, neither physical nor metaphysical, signals Singer’s flight pattern.

If there is a movement in the history of art that inspires him most, it is surely the Baroque, a movement reckless and wanton and uncaring and fearless. For it is then, for the first time, that art refuses a ground and fulcrum. Mistakenly assumed to be merely obsessed with elaborate detail, and damned because of it, because its supposedly refused the bigger picture, Baroque art is in fact feared, then as now, for a very different reason – because it is treacherous, because it refuses a core and will not compose itself well. It is wild, immoderate – Apostate. It bows down neither to the Law of Culture nor the Law of God.

Which is why it appeals to Singer, why, for him, it is the only way out of the mess we find ourselves in.

We are despairing, craven, nonplussed, feckless, and, as a counter, fanatically fundamentalist. In choosing Alexander’s Butcher Boys as our crucible we choose to remain consumed by dread. In choosing Boshoff’s Blind Alphabet, we choose the endgame of mind. In veering back and forth between manic glee and existential angst, Young’s bipolar world, we succumb to a rigged playing field – to weltschmerz, world weariness.

All of these visions are true, but none of them will save us. What we need to do is junk our pain, trash our fixations and fetishes, forget about history, forget about God. How else will we ever take flight?

Featured image: Ed Young, Arch, 2010. Mixed media.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory