Special Project ESSAY: Tracing Modernist Lineages

Curated by Latitudes Co-Director Lucy MacGarry in collaboration with Peffers Fine Art

Form and representation: Exploring the work of Sydney Kumalo and Amalie von Maltitz

- by David Mann

Amalie von Maltitz in her sculpture garden, still from video produced by RMB Latitudes

Amalie von Maltitz in her sculpture garden, still from video produced by RMB Latitudes

----------------------

For the sculptor, a sketch might be a provisional thought, a way of quickly and effectively committing an idea to paper, but there is also a vital relationship between sculpture and drawing – one that sees each practice informing and deepening the other. This year, RMB Latitudes’ Special Project, ESSAY, focuses on the drawings and sculptures of two prolific South African artists, Sydney Kumalo and Amalie von Maltitz.

Latitudes launched ESSAY in 2019 as a platform to spotlight rarely-seen work — bringing emerging artists and overlooked masters into sharper view. The inaugural presentation featured then lesser-known artist Sthenjwa Luthuli alongside the revered sculptor Pitika Ntuli. By 2023, ESSAY had evolved into a dynamic cross-generational conversation between Sam Nhlengethwa, Katlego Tlabela, and Cinthia Sifa Mulanga. In 2024, the platform turned its focus to two relatively under-the-radar artists: Wendy Vincent and Geoffrey Armstrong. With each iteration, ESSAY has grown into a more deliberate and confident curatorial voice.

This year’s ESSAY is presented in the Chapel space, and pairs the charcoal and pastel drawings of Kumalo with the clay sculptures of Von Maltitz. The relationship between these two artists might not be immediately apparent, but the resultant dialogue between their work is intriguing.

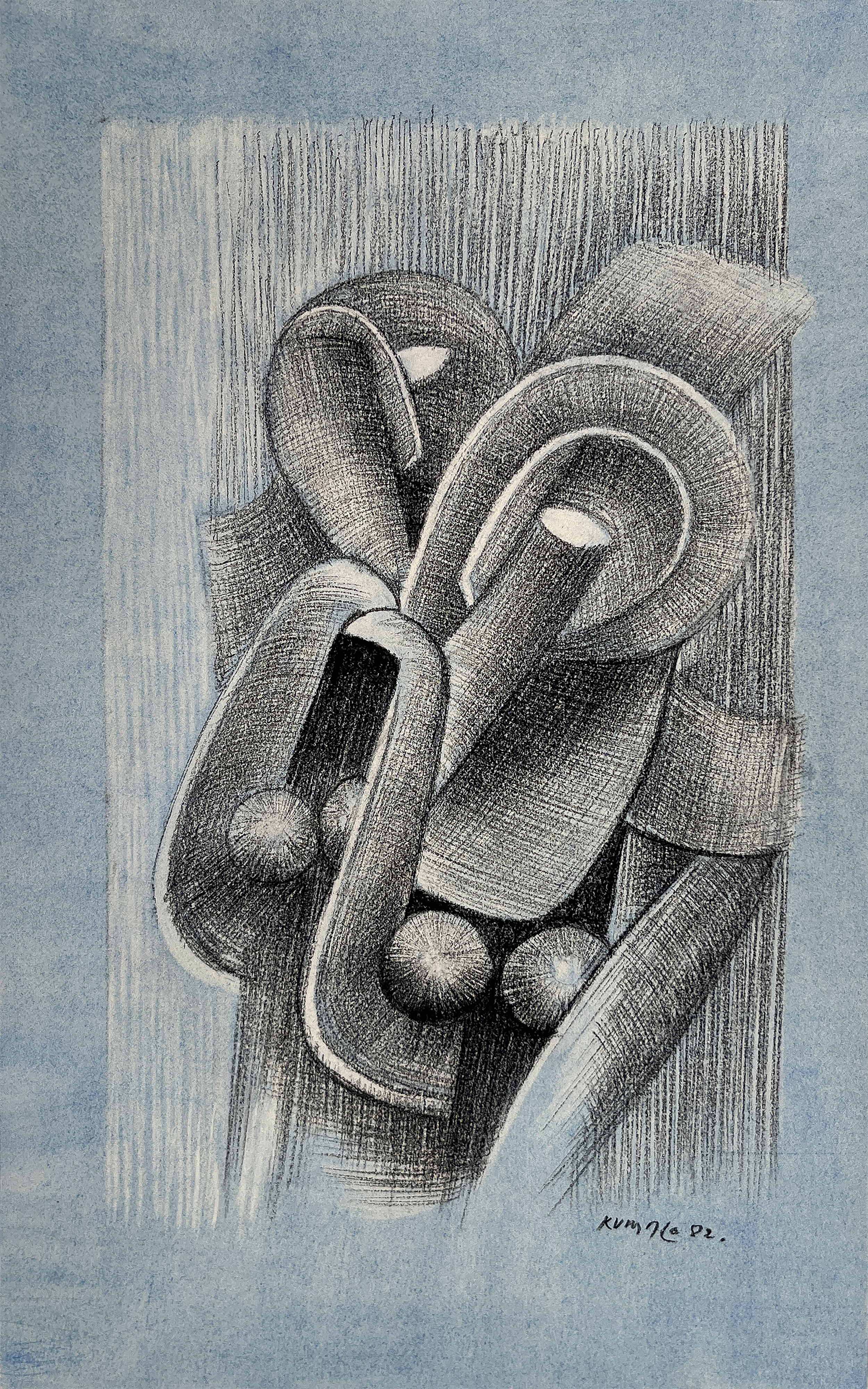

Sydney Kumalo, Untitled Dancing woman, 1982

Kumalo, who passed in 1988, is a significant figure in South African sculpture who exhibited both locally and abroad during his lifetime. Von Maltitz, who still lives and practices from her home in Johannesburg, has exhibited locally, but is perhaps best-known for her work as a teacher of sculpture. Both artists, however, have left their mark on South African sculpture through their respective approaches to figuration, abstraction, and their consideration of the human form. And while their paths diverged and crossed, never quite meeting, their work shares a few key influences.

Populating the lush garden of Von Maltitz’s Westcliff home are sculptures that span the length of her career to date. All of them have a striking vertical presence, at least a metre tall, and many of them have been coil-built in clay and fired as two or three separate pieces. Across the garden is her studio, attached to the main house which used to be a large horse stable. Von Maltitz has lived here for more than 40 years, now. Her mother, also an artist, used to paint in the same studio that Von Maltitz now works and leads her classes – the Stalhuis Sculpture Studio.

Amalie von Maltitz sculpture garden

Amalie von Maltitz sculpture garden

In 2021, a fire broke out on one side of Stalhuis, melting and warping many of her materials, maquettes, and other studio bric-a-brac. She’s chosen to leave it as is, curious about what it might do to her practice.

As I’ve tried to get closer to the essence of things over the years, I’ve moved more into abstraction and further away from traditional ways of working. These things happen subtly,” she says. “There’s an organic development that you grow into as you work. You get a suggestion of what you should be doing and where you should be going with each attempt, but you have to keep at it.

Amalie von Maltitz, in studio

Von Maltitz has been at it for a long time. Enrolling at the Michaelis School of Fine Art in the 1960s, she went on to pursue her post-graduate studies at the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Art in Germany. After returning to South Africa, she began teaching, and though she continued to make her own art over the years, teaching became her primary focus.

Back in 1952, when Von Maltitz was still in school, Kumalo was starting at the Polly Street Art Centre. It was here that he met Cecil Skotnes as well as the art dealer and collector Egon Guenther who connected him to many of the important galleries and institutions of the day. Kumalo also taught art, but only for a few years, choosing instead to focus on his practice full-time. He became recognised early on for his talent. Even within the complex context of apartheid-era South Africa, he exhibited both locally and internationally, including showing work at the Venice and São Paulo Biennales. Together with Skotnes, Edoardo Villa, and Giuseppe Cattaneo, he founded the Amadlozi Group, which advocated for an African identity in art and became an important reference for many artists at the time, including fellow sculptors such as Ezrom Legae.

Though the two never met, they shared a common mentor at different times in their careers – the Italian-South African sculptor, Edoardo Villa. While Kumalo met Villa in the late 1950s, Von Maltitz first encountered him while working at the University of Johannesburg (then called the Rand Afrikaans University) in the 1970s. She would later write her Masters thesis on his work, and curate two major career retrospectives of his. How did Villa’s work influence hers and Kumalo’s?

“There was a period of cross-pollination,” Von Maltitz explains. I think Edoardo helped Kumalo model his sculptures more freely, more directly. And in some early bronzes of Villa’s you can certainly see echoes of the Kumalo style.”

The verticality of both artist’s works, as well as the simplified, almost geometric approach to form, are other stylistic traits that may very well have been inspired by Villa.

Kumalo and Von Maltitz would go on to find their signatures. For Kumalo, it was the physical and spiritual relationship between the human body and the animal body that surfaced in his drawings and sculptures. Von Maltitz, following trips to national parks across South Africa, Namibia, and Utah, would go on to create forms that strongly echo those found in nature.

Both artists convey a sense of volume and mass in their work, owed to the controlled movement and simplicity of their forms. In their drawings and sculptures alike, the images they present are layered and complex, but the execution is one of practiced simplicity.

Sydney Kumalo, Untitled Study for sculpture, 1982

Amalie von Maltitz, sculpture, photograph by Jarred Figgins

In most cases, to look at one of Von Maltitz’s drawings is to see a blueprint of a sculpture. She takes pleasure in the technical processes of building and firing in clay, and her drawings often serve as the aspirational schematics. Later on in her career, she stopped drawing altogether and went straight to maquettes instead.

Kumalo on the other hand, used drawing as a speculative exercise. His early charcoal drawings are mostly studies for sculptures, and it’s his sculptural work for which he became known, but he continued to draw alongside his sculptural practice, eventually venturing into pastels and playful, abstract forms. Always, though, the charcoal remained.

In Kumalo’s charcoal drawings, there is an undeniable relationship to his sculptural forms, but there are also those drawings that venture into the surreal, adopting their own grammar, their uniquely fantastical anatomies. Free to venture beyond the limitations of bronze, his drawings embraced complex patterns and labyrinth-like structures.

Sat alongside one another, Kumalo’s drawings and Von Maltitz’s sculptures enter into an interesting conversation. There is a dialect, or a lexicon embedded in each of their works. For Kumalo, it’s the dotted forms and angular, almost cubist iconography of his drawings. Present in Von Maltitz’ later works is the letter-like formation of her interlinked forms. Together, their work forms an interesting visual narrative, and perhaps even charts a journey of South African modernism moving into the contemporary.

Finally, it is the conscious move towards abstraction that is most evident in their respective drawings and sculptures. Kumalo's work, steeped always in aesthetic consideration, grew into a type of abstraction rooted in representation. His drawings, with their meandering folds and grooves, became a way of dreaming beyond the sculpted form.

For Von Maltitz, it is an attempt at getting to the essence of form and representation, “a way of getting another kind of discipline, and going towards basic shape.” Here, the relationship between drawing and sculpture returns. As Von Maltitz explains: “I think [drawing] can be an important process to find the basic shapes, not necessarily always to sculpt them, but to think differently about sculpture.”

Amalie von Maltitz, sculpture, photograph by Jarred Figgins

Amalie von Maltitz, sculpture, photograph by Jarred Figgins

Kumalo and Von Maltitz experienced varying degrees of recognition for their work, and in many ways, a pairing such as this highlights the complexities of visibility that continue to exist in South African art. Beyond providing a unique perspective on the artistic practices of two important South African artists, and contributing to a deeper understanding of South African modernist and contemporary drawing and sculpture at the margins, an exhibition such as this also performs the simple and vital function of continuing the conversations and points of inquiry being pursued in their work, with a new audience.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory