Kilelo Milelo – Effo Munguanzo’s debut solo exhibition is confrontational

- By Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti

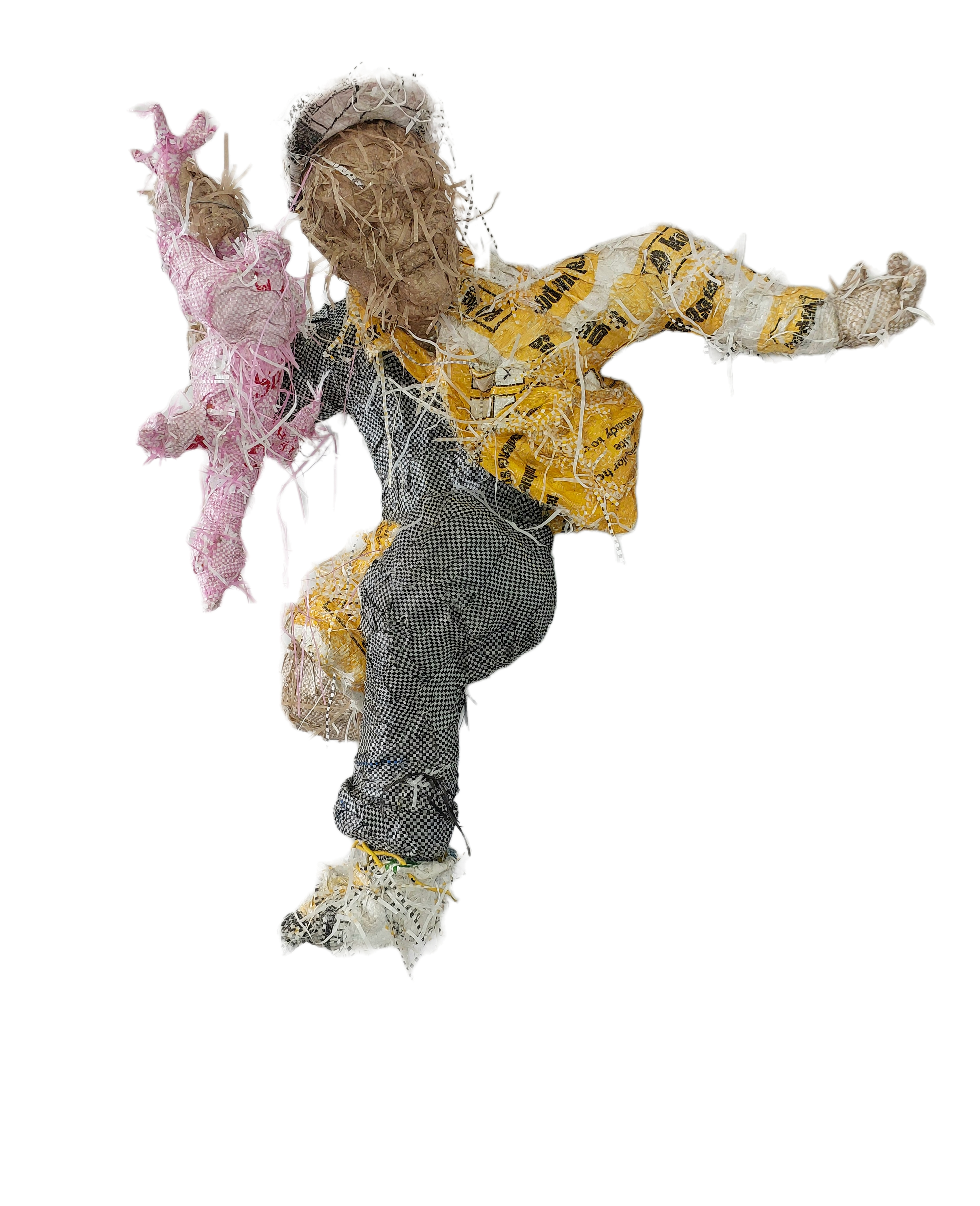

Effo Munguanzo, Moyibi ya Soso (Chicken Thief), 2023, Mixed Media Found objects on styrofoam core, varnish, image courtesy of the artist and the AVA Gallery

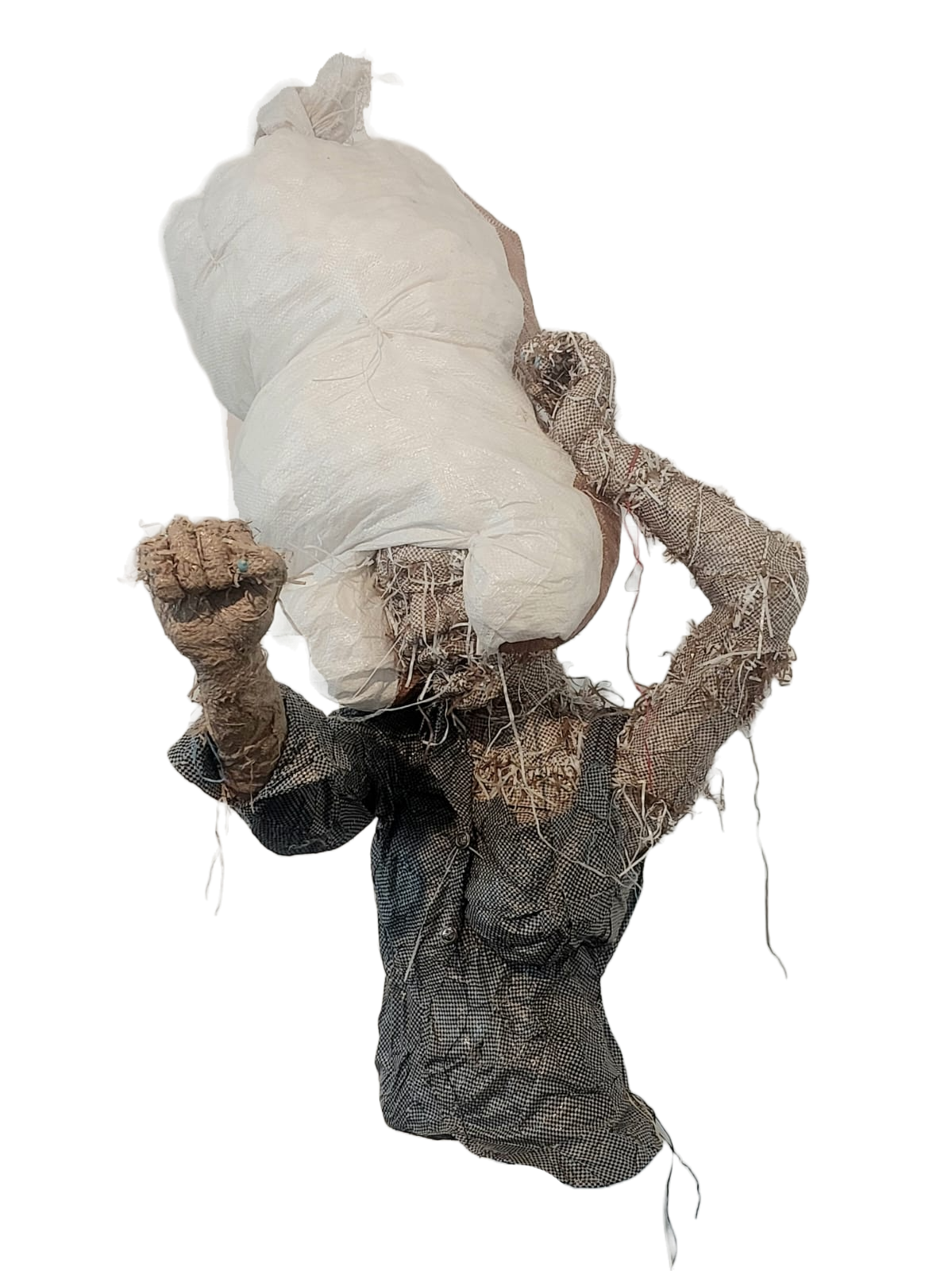

We have seen it carried by the internally displaced migrants fleeing intercommunal violence, especially in the north-eastern epicentres of conflict like Goma and Bukavu. We have seen it on the heads, backs and shoulders of the shirtless and bare-footed children who toil as washers and diggers in the central African nation’s dangerous mines. We have seen it in the hands of the United Nations World Food Programme aid workers distributing food and clothes among the displaced. The polypropylene woven sack is such a common fabric on the landscape of the world’s most mineral rich, yet poorest and most unstable country, the Democratic Republic of Congo (hereafter referred to as DRC), that its citizenry cannot function properly without it. As such, it is not surprising that the Kinshasa-born and trained artist, Effo Munguanzo, appropriates the bag, employing it as a medium for his colourful three-dimensional sculptures which help him tell the stories of his troubled country of birth. Through his practice, the artist breathes life into the used and discarded old bags which he gathers among the migrant communities in South Africa, with some of them having been brought here from as far as the DRC.

Titled ‘Kilelo Milelo’ (Today we Cry), Munguanzo’s debut solo exhibition at the AVA Gallery’s mezzanine in Cape Town (19.01.23 - 02.03.23) captures and contemplates the life of the ordinary people of the DRC in the post-covid lockdown era when life worsened for most. The title is in Lingala, one of the languages spoken in the country. The phrase, which denotes suffering, is colloquial and mainly uttered by the youths. The agony of the post-lockdown phase is expressed in Masuwa (Ship passenger), a wailing figure placed right in the centre of the exhibition, and in Eclipse which portrays an individual on the move, with luggage on the head, possibly all the belongings. It is also articulated in Lelo (We are crying) and Kanisa Pona Lobi (Think for the future), two works in postures reminiscent of David Ndlovu’s Thinking man situated at the Civic Centre in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. These works express anguish and suffering, as has been the case of society’s lowest classes in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Effo Munguanzo. Masuwa (Ship Passenger), 2023. Mixed Media Found objects on styrofoam core, varnish, image courtesy of the artist and the AVA Gallery

The main subject addressed in this body of work is heavy and unbearable, yet Munguanzo still manages to express it through caricatures and therefore doses of humour at times. In Jeux de Enfant (Children’s games) and Moyibi ya Soso (Chicken thief), the artist makes damning commentary of politicians who sell empty promises to the populace and steal from the public coffers. True to the scenarios often seen in the Congo, and Africa in general, the politicians are stylishly dressed. In a similar scenario, I am reminded of a politically well-connected Zimbabwean who was granted a tender for a state-sponsored solar power project and turned up parading pairs of sneakers on social media, with no single solar farm constructed. No one held him accountable of course!

Even the politicians that lie and steal from the people often have followers and disciples who praise and worship them. The continent of Africa is no stranger to airport scenes of ordinary people dressed in ruling party regalia, drumming, ululating, whistling, singing, and shouting praises at leaders returning home from foreign summits, albeit mostly empty-handed. The tradition of eulogising and idolising the ‘big men’ in politics is something that started long back in the DRC, in the days of the long-gone dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, when the country was still named Zaire. Popular stylishly dressed rhumba musicians would compose songs after the politicians. Interestingly, the tradition – witnessed by the artist from a young age – has carried on to this day. Munguanzo would like to see the end of the culture, hence in Djalelo (Guitar), he intentionally collapses the depiction of the praise singer.

Effo Munguanzo, Eclipse, 2023, Mixed Media, Found objects on styrofoam core, varnish, image courtesy of the artist and the AVA Gallery

The conflict in the DRC is so complicated that it implicates neighbours Uganda and Rwanda. That the two respective nations have a hand in the conflict is not a secret. In fact, both countries are known to export diamonds, a resource non-existent within their borders. How the western world buys from them without questioning the situation speaks to the shameless double standards and despicable contradictions of capitalism. Munguanzo introduces Bi Mado, the bust of a woman adorned in a beautiful headwrap which matches the blouse. She has big lips. Seemingly out of sync with the rest of the pieces in the show, the artist explains that the character is a portrayal of the well-adorned appealing females on spying assignments to the DRC on behalf of its neighbours, especially Rwanda. Such women, on a mission of siphoning information, are the silent footsoldiers in the destabilisation of Africa’s most turbulent nation.

Effo Munguanzo. Mile Lelo (You are Crying), 2023. Mixed Media Found objects on styrofoam core, varnish, image courtesy of the artist and the AVA Gallery

Some of Munguanzo’s impeccably dressed figures have both masculine and feminine features and characteristics. I put this across to the artist who tells me a rather sad story of how he never got to really connect with his absent father who served in the army. His mother passed away when he was still young and as such, she had not fully shared the reasons why the father left. For the artist, the depiction of androgynous individuals is a way of soul searching, recognising, and respecting both parents he never really got to know and striving to find meaningful answers to questions within.

If you're in the habit of searching for positive stories that shatter stereotypes on the African continent, perhaps Munguanzo's exhibition is not for you. The artist has no time to ‘fabulate’ or put a spin on the narrative to mask the appalling situation in his country. Sometimes all insiders of troubled communities desire are for their stories to be heard out there. The most we can do is respect their agency, appreciate their courage, and draw valuable lessons from the shared stories. Unlike the oft-repeated media photographs of the situation in Congo, which admittedly make us feel indifferent oft-times, Munguanzo's creative output makes us stop and ponder. It is serious, conceptual and confrantational. The artist offers us an opportunity to travel to his country of birth in our imagination. Although most of the figures in the show tell sordid tales, the bag they carry and/or are made of is synonymous with migrating individuals fleeing areas of conflict yet spurred with hope for a settled and peaceful future. It is a pity that capitalism thrives on a chaotic DRC.

- Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti is a Cape Town-based art researcher and writer with interests in Modern African Art and Contemporary Art

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory