Cut & Paste art exposes the gaps in historical and digital archives

- By Mary Corrigall

---------

Lakin Ogunbanwo, Chillin’ in my Cerebellum, 2023, courtesy WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery

The contemporary condition is such that there are no longer any art movements – even if there are discernible aesthetic or conceptual qualities characterising the art finding favour. This is largely due to transitions moving in short cycles and existing in parallel to other discernible trends, and certainly they are not bound by elaborate manifestos as per Europe's avant-garde culture. This leaves art historians or commentators insufficient time to name or claim them.

Yet currently, it is possible to draw a fairly straight line between several artists' practices which evidence a playful if not surrealist manipulation of archival imagery or photographs. The artists that come to mind are Teresa Kutala Firmino, Phumulani Ntuli, Thato Toeba, Neo Matlogo, Lunga Ntila and newcomer Kaelo Molefe. Even established documentary-style photographers such as the Nigerian Lakin Ogunbanwo have taken to manipulating photos, arriving at sometimes abstract compositions.

This is not a new way of working, collaging with found imagery dates back to European Dadaists such as Hannah Höch. In the African art context, Sam Nthlengethwa (who was inspired by the African American artist, Romare Bearden) has been incorporating found images in his paintings since at least the 80s and Wangechi Mutu, the Kenyan-born artist has in the last decade enjoyed much success in the US exploiting the collaging mode to evoke hybrid beings with a foot in the past, future or the natural world.

Yet, here we find a group of young, emerging and established African artists employing collage in paintings or paperworks centred on collaged photographs, mostly to arrive at strange-looking subjects with fragmented bodies or faces. What might be compelling another generation to regurgitate, reinvent, consume and alter existing images?

It could be a way to renew the possibilities in painting and photography. Given some of the above-mentioned artists combine and blur the lines between these mediums, they might be interested in the tension between truth and fiction. Documentary photography has been impacted by technology. Everyone has a camera on their phones.

Lakin Ogunbanwo, Its only gluttony if you feel guilty

“I do think our relationship to photographic images has changed for sure,” says Ogunbanwo.

“When I was younger my family and I would dress up to go to the studio to get a family portrait. Now people are constantly capturing beautiful moments on their phones every day,” he adds.

This culture has not only forced photographers to carefully consider what images would have social or artistic resonance but, says Ogunbanwo, has given rise to an excess of images – veritable archives of imagery to be consumed – in creative ways.

Ogunbanwo’s new collage works, which debuted at the FNB Art Joburg's WHATIFTHEWORLD's booth, see him reworking, and recontextualising his own archive of images, though he says in the future he may consider working with found images or those from specific archives. It was following an encounter with El Anatsui years back that left him with a nagging desire to identify ‘materials’ that were like second nature to him.

“I was on a portrait assignment for the New Yorker to shoot elements in his (Anatsui’s) studio in Nigeria. I was asking him about his process. I asked him specifically how he knew he had hit the jackpot with his sculptures. He said he chose to work with materials familiar to him, which were old bottle covers. He also said it wasn't about knowing, it was about playing,” recalls Ogunbanwo.

It has taken some time for Ogunbanwo to realise that the most familiar materials to him were his own images. In creating collages with his own archive, he has been able to reconsider and appreciate different characteristics of work, looking beyond the subject matter. Colour and textures have always been important to him - given his link to the fashion world - but in this context, these qualities took on a different function. He could juxtapose textures from different images in places in time. This freed him up from his documentary practice but also allowed him to make abstract works.

“With photography what is special about the medium also limits it. It captures the truth that the photographer has made up but also truths that just exist,” says Ogunbanwo.

In some of his collages, a human body is discernable, but through this medium, it is rendered expressively. In other works, the ‘truth’ – its connection to the figurative world – is denied through a swirl of images caught up in a whirl of sorts, implying that the seen world is beyond grasp.

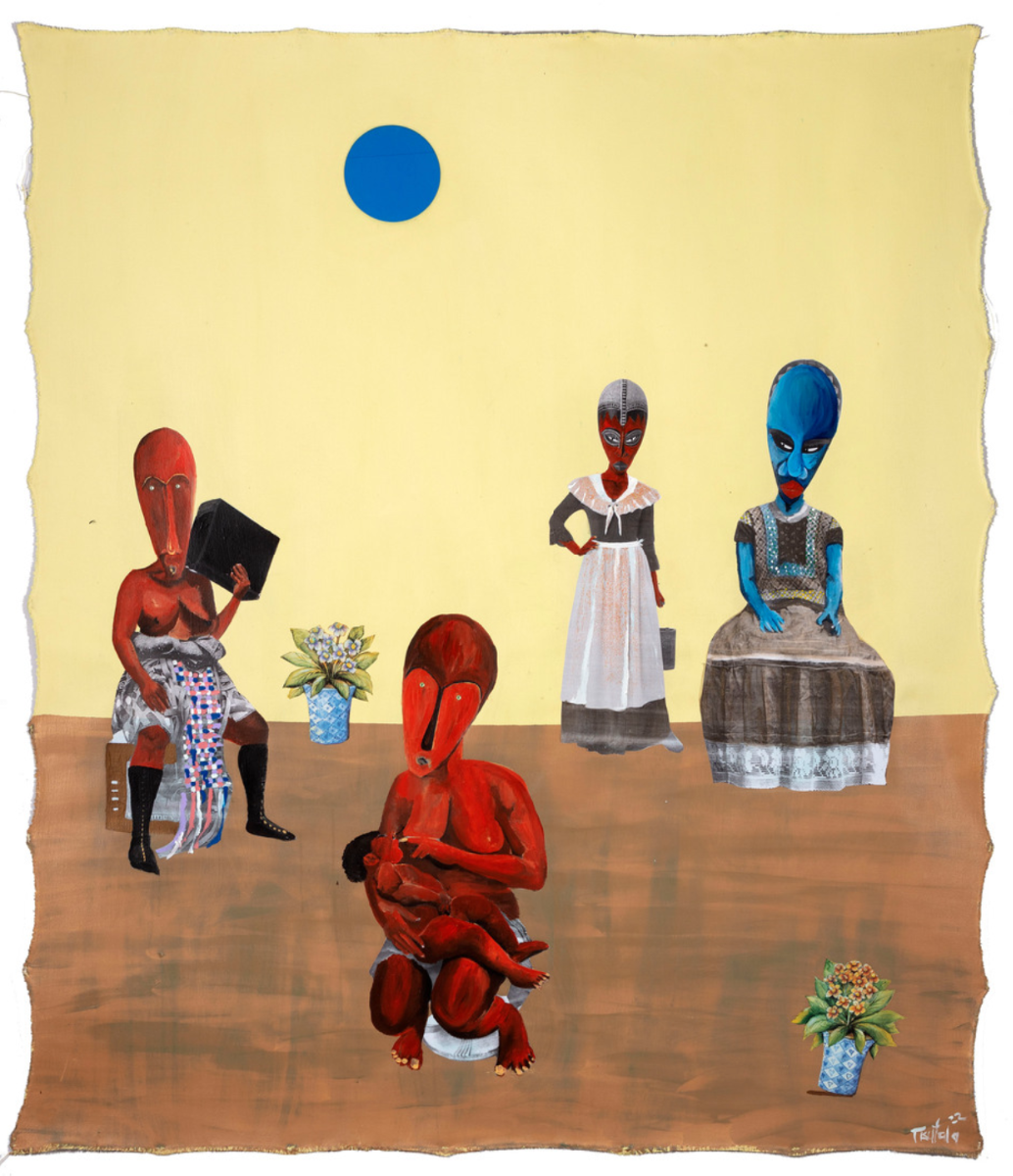

Teresa Kutala Firmino Njuju Tree, 2022, courtesy Everard Read

This notion resonates with a comment Ntuli made when he was discussing his practice ahead of it being featured on the South African Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2022.

“I am interested in the collision between reality and fantasy because something happens when they meet. I think memory becomes so unreliable because it is fragmented, it’s like a piece of a puzzle or as a frame of a photograph,” said Ntuli.

This mode/medium of expression presents a shift in the position of the photographer artist, or artist working with photography – they are not beholden to framing a moment in time, but reframing it. As such collaging with images is concerned with the role of photography in reconciling with history and as Ntuli suggests the shortcomings of doing so.

Firmino’s family history is often raised in introductions to her work. Born from parents who both escaped conflicts in their native countries (the Congo and Angola) and having grown up in a town in South Africa where some of the local population are former soldiers of the 32 Battalion (an army of black South Africans who fought for the Apartheid state) it is assumed that any understanding of her art relies on knowing that she is haunted by social and political tensions.

This may have set her on the path to combining photomontage with painting. However, in more recent works, her mode of incorporating collaged heads and other elements of the mostly female subjects that feature in her art seems tied to how the female body is presented, celebrated and objectified. There is a historical thread to this theme but in the work Lust, Consumption, Needs (2022) for example, where two cameras are positioned on either side of a female subject, it is easy to imagine Firmino is interested in how the proliferation of cameras and constant documentation of the self has given rise to many public permutations, but also has collapsed fixed notions of the ideal body. Firmino’s subjects are voluptuous and proud, but ever conscious of the camera, the gaze of many. The proliferation of social media has democratised the ‘gaze’ but it has also heightened the necessity to craft a variety of public personas that may not coincide with a private shifting self, causing a pervasive sense of dissonance.

The collage mode suits articulating the fragmentation and perhaps fractures that bear down on identities performing for different publics. It provides a language to show the constructed nature of the public self and the variety of public selves that are literally pasted onto an ever-evolving body – and set of contexts.

Collage affords the artist, maker, agency over history and the biases that have shaped certain archives, forever fixing some subjects in a ‘gaze’ that sought to subjugate them.

This relates to Kaelo Molefe’s practice. In line with the works, he is currently showing at his exhibition at Kalashnikovv gallery titled Other Schematics he reworks, and scrutinises, a largely ‘scientific’ archive (though images are derived from multiple sources) from the 19th Century used to justify racism and imperialism. Having studied medicine Molefe is naturally interested in the role science has played in defining the body under the titular schematics.

This background has also shaped Molefe’s approach to dissecting archives, in the way that he isolates small parts of existing material, as if studying it under a microscope, before reconstituting a new image. The new image is never whole - the parts float at a distance from each other. In this way, the body is truly fragmented, and he uses these ‘gaps’ to insert lines or other images unrelated to the human body to draw attention to the other parts that constitute the self.

In The Running Man (2021), a cut-out of a cityscape stands in for a chest and could refer to not only a contemporary condition but the ties that bind the titular man to a place that is embedded in his body.

In an interview with the now-defunct New Frame, Molefe suggested that collage is an inherently “political medium” as it allows him, or other artists for that matter, to not only disrupt historical narratives but “reconfigure their meaning”.

Collage also affords artists the ability to communicate the lingering impact of historical narratives. While there is a sense of disjuncture in the art of Ntuli, it is much less pronounced. He uses collage in conjunction with painting and printing to draw attention to how historical social, political or psychic patterns pervade the present. In this way, the bodies he presents consist of a collaged pattern.

Ntuli’s works are pleasing to the eye due to his approach, but also his pastel palette is soothing. This suggests a time gap between the present, where his subjects exist and, between the black-and-white images/prints evoking the past that dominate his subjects' frames.

Phumulani Ntuli, Zama Zama, R146,930.00 ex. VAT, ENQUIRE

Phumulani Ntuli, Zama Zama, R146,930.00 ex. VAT, ENQUIRE

In the information age, Ntuli’s practice also engages with the proliferation of data. This came more sharply into view in his recent solo exhibition of works for David Krut under the title Kunanela iphuzu emafini / Echoes of the Point Cloud.

In an interview relating to that body of work, he observed that he viewed collage as a response to how reality is being reframed not simply via images but how data is being organised. From this perspective, collaging emerges as an art form that mirrors the process of reconstituting existing information. However, as these artists make the cuts and slices and the act of rearranging the truth visible, they draw attention to gaps in our digital realities.

Corrigall is a Cape Town Based art commentator, advisor and researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory