Curator's Journal:

On Independent Cultural Production in Johannesburg

- by Nkhensani Mkhari

------------

© OtherNetwork, photo: Thabang Radebe

Before I go on, allow me to say as pertinent as it may be, this essay doesn't seek to be a survey or draft a conventional map of the Independent Cultural practices in Johannesburg - we’ll save that for a longer text; rather, it serves as reflection on the impetus of independent cultural production in Johannesburg through my personal experiences over the past several years.

Lately I’ve been reflecting on how every September since I got to Johannesburg, I’ve been frequently confronted by how within the intricate terrain of South Africa's art ecology, the independent cultural production sphere often finds itself eclipsed by the hegemonic force of the booming commercial art world. A pervasive obscurity ensues, primarily stemming from the glaring deficiency of financial patronage or state support, a circumstance that relegates these vital spaces to a precarious existence with an average longevity barely reaching 2 to 3 years, while languishing in extended periods of dormancy.

My entanglement with this discourse was catalysed by an invitation to participate in a panel on Independent Cultural Production featuring Sinethemba Twalo of the imitable NGO (Nothing Gets Organized) and Mpho Moshe Matheolane, art historian and Think Doctoral Fellow. The panel was convened by OtherNetwork, a digital collaborative platform connecting independent art spaces globally, initiated by COOKIES and ifa. Hosted within the evocative confines of The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember, an initiative birthed in 2017 by the visionary Zimbabwean artist, Kudzanai Chiurai.

My initiation into the world of Independent cultural production was a whirlwind affair, a rendezvous with the avant-garde Pool Space tucked away downtown on the corner of the ground floor of Ellis House back on the auspicious evening of March 15, 2015. The alchemical collision of minds behind this exhibition: Mandla Mlangeni - Jazz extraordinaire - and maestro of melodies, Shane Cooper, visionaries in their own right. This exhibition was woven into a series christened Starter Room.

Sitting on the floor, back against the wall, a playground of experimentation and médiathèque marvels unfurled before me. Picture it: an audiovisual dialogue reimagining of plant relations, structures, and substrates, all conscripted into service as fertile terrain for the serendipitous dance of the poetic, the social, the political, and the biological.Whispers of untold narratives and clandestine forms of enlightenment beckoned us forth carried along a resonant bassline. Plunging us headlong into the hitherto unheard and the wholly unexpected.

Now, let me set the scene – I was a fresh arrival to Johannesburg, a neophyte in the 'artworld', still grappling with the throbbing pulse of this vibrant metropolis. But that evening, at Pool Space, I was bewitched. On my way to grab some drinks with friends afterwards, I felt my preconceptions of artistic production and perceptions of artistry itself dissolve and transmogrify. That night breathed life back into my capacity to dream. I kept visiting show after show and my network expanded, leading me to connect with more independent project spaces and collectives in the city.

Something that left an indelible mark on my artistic sojourn to these spaces and gatherings was the distinction in the audience's makeup from the white cube galleries uptown – for these soirées predominantly unfolded within the inner city's embrace – a palpable sense of community, a camaraderie that I continued to see thrive within these hallowed creative sanctuaries. Here, human connection reigned supreme; people actually saw one another and engaged in the raw essence of each other's lives. There was a deep sense of warmth and belonging. The strength of these spaces was the strength of the community.

MADEYOULOOK Kassel 2022 Photo: Frank Sperling

MADEYOULOOK Kassel 2022 Photo: Frank Sperling

Whether it was a gathering hosted by the enigmatic MADEYOULOOK, the anarchic fervour of Nothing Gets Organized, the subversive spirit of Keleketla, the playful rebellion of Bubblegum Club, the conceptual brilliance of Wherewithall, or the soul-stirring resonance of Lapa, a common thread ran through the fabric of the spaces these entities created. An unmistakable aura of the avant-garde and the underground pervaded the air, where artistic expression flowed without the constraints of commodification pressures that plague mainstream art. In this sphere, the boundaries of the independent cultural production space extended limitlessly, fuelled by an inexhaustible creative engine propelling us toward an audacious future, an alternative portrait of what South African contemporary art can be and, indeed, what it already is.

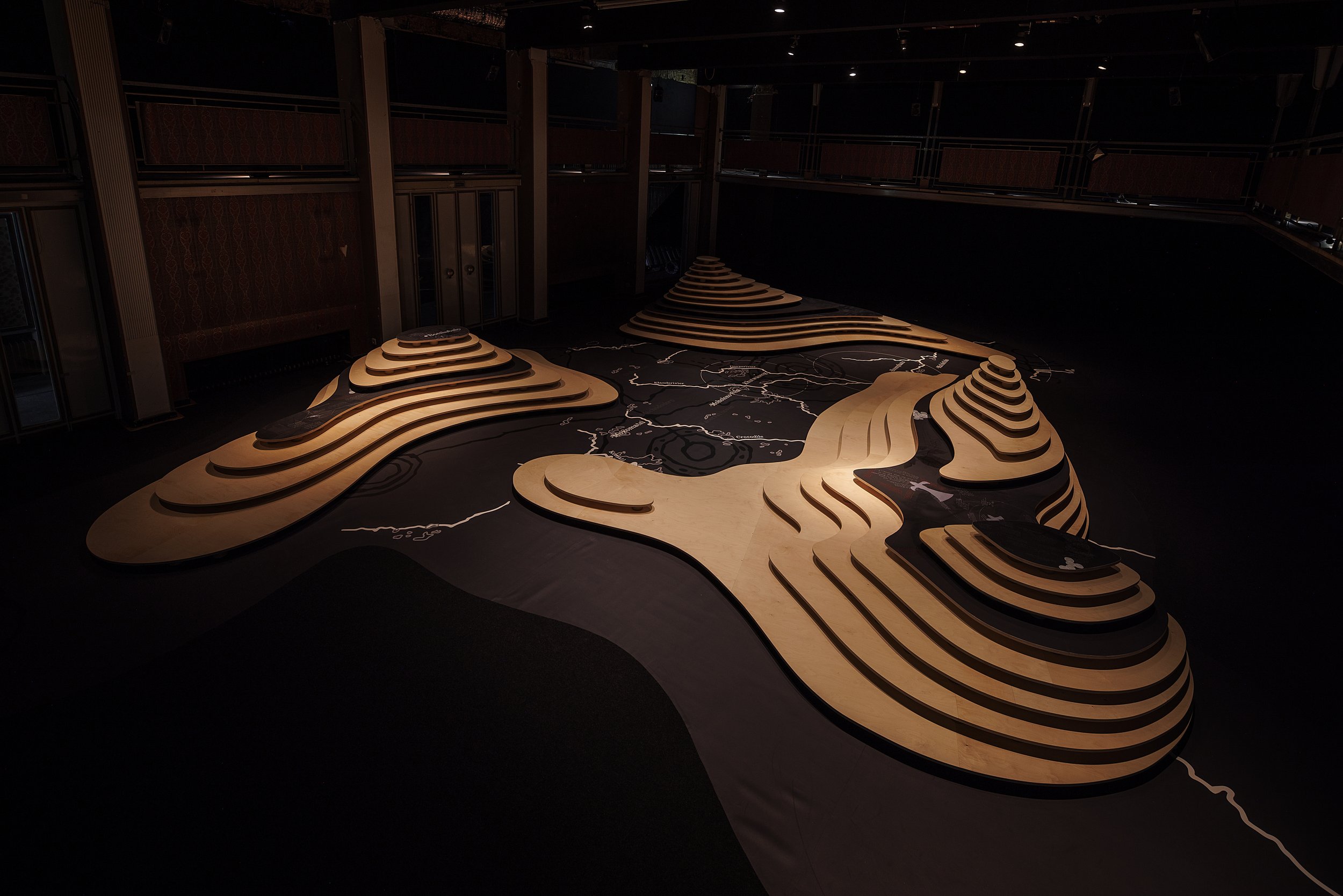

© OtherNetwork, photos: Thabang Radebe

So, when I stumbled upon the work of MADEYOULOOK at Documenta 15 last year titled ‘Mafolofolo’ I felt a deep resonance. ‘Mafolofolo’ emerges as a sanctuary of recovery, born from years of unwavering research. The project delves into the intricate web of loss and the subsequent resurgence entwined with the land's very soul. Traversing the tumultuous epochs of South Africa's history, ever persistent and destabilising, to unearth the enduring bonds that tie us to this sacred earth.

The floor installation served as both a site of mourning and a haven for contemplation, an offering of strategies to mend the broken threads of existence. The unending cycle of displacement and return is etched into the very fabric of this space. The resonance of sound, an ode to the African resistance songs that echoed across the land, particularly in the battle for emancipation and autonomy against the dominions that strived to stifle our soul's fervor. This work offered a glimpse of hope—a chance for new imaginaries of connection with the land, an opportunity to transcend the shackles of the past and forge a path towards a different, more profound communion.

However, I kept thinking about how beneath the veneer of this mega show, Europe stands as an active crime scene, a place where Africans were forcibly transmuted into colonial subjects. With the weight of this thought in mind, the artworks on display became a testament to the complex web of simulacra that facilitated this transmogrification. This tension, one not confined solely to the political frictions that unfurled at Documenta 15, resided in the sobering reality that those whom the work spoke of may never experience it, imprisoned as it is within the confines of European borders. And so, the conundrum persists.

This thought raised a pivotal question—could the issue at hand transcend location and instead revolve around the dearth of events akin to Biennales and Triennials within South Africa? This vacuum results in our culture being exported without us ever bearing witness to its unfolding, even though we’re integral to its immanence. The pressing query for cultural practitioners, curators, directors, and critics is how to craft a sustainable way to bridge this chasm? With our best talent often moving abroad, or seeking refuge and belonging beyond our borders, perhaps the echoes of our identity, commodified before being relinquished to us, will stir change or fall on deaf ears.

In the panel discussion the query of how can we harness the crucible of South Africa's burgeoning independent cultural production loomed large: how do we carve out the necessary space to harness its vitality and counterbalance the relentless sway of commercial interests that presently dictate the narrative? OtherNetwork aspires to forge connections and facilitate idea-sharing among such talents and the spaces they occupy globally. Yet, the challenge remains—how do we nurture these local spaces and the curators and artists who inhabit them, ensuring their sustainability and expanding their influence to reach broader audiences?

I proposed a strategy I often use; Parasitic Mutualism. A symbiotic relationship in which both species benefit. This idea is inspired by the pioneering work of Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick in their seminal text A Productive Irritant:Parasitical Inhabitations in Contemporary Art which was inspired by Michel Serres The Parasite. Serres contends that the parasite, often seen as a negative or harmful entity, plays a crucial role in ecosystems by contributing to their complexity and stability. He suggests that parasites are not just destructive but also serve as agents of transformation and adaptation. Daringly, he proposes that all relationships are fundamentally parasitical.

Definitions of the parasite:

- To one side of (para) the location of the event (site) – the medium or being through which communication must pass.

- The ‘static’ that interrupts the transmission of a message.

- The uninvited guest or ‘social’ parasite.

- A living organism that takes without giving as it infects its hosts

- The one who is always near to food, close to the meat

- A thermal exciter, that which catalyses the system to a new equilibrium state

Parasitic strategies are, at heart, a revolt of the creative spirit—an arsenal of critique and subversion. They can serve as a formidable tool wielded by artists in their quest to dismantle entrenched norms, question institutional authorities, and shatter the barriers of the status quo. By infiltrating the hallowed halls of existing spaces and systems, artists and curators can illuminate the oft-overlooked fault lines in our social, political, and cultural landscapes, compelling society to confront its own reflection. This isn't art held captive within gallery walls; it's art thrust into/from the raw and unanticipated spaces of public discourse, sparking discussions on the intersection of public ownership, the sacred realm of creative expression, and the relentless commodification of artistic ingenuity.

By disrupting the established systems and spaces, parasitical mutualism can awaken us from the slumber of complacency and the jaws of excessive aesthetic acculturation contributing to cultural homogenization—both within the confines of the art world and in the broader realm of societal norms. They serve as a stark reminder that art isn't confined to mere aesthetics; it's a dynamic force that challenges the entrenched paradigms, paving the way for transformation.

Ultimately, parasitical strategies invite us to reenvision the boundless possibilities of art ecology. They liberate creativity from its predictable confines, beckoning a spirit of experimentation and innovation that resonates with artists and audiences alike. While strategies such as these may at times dance on the edge of controversy and confrontation, their enduring productivity lies in their capacity to ignite vital conversations, kindle social engagement, and elevate artistic expression beyond the confines of the expected to the extraordinary.

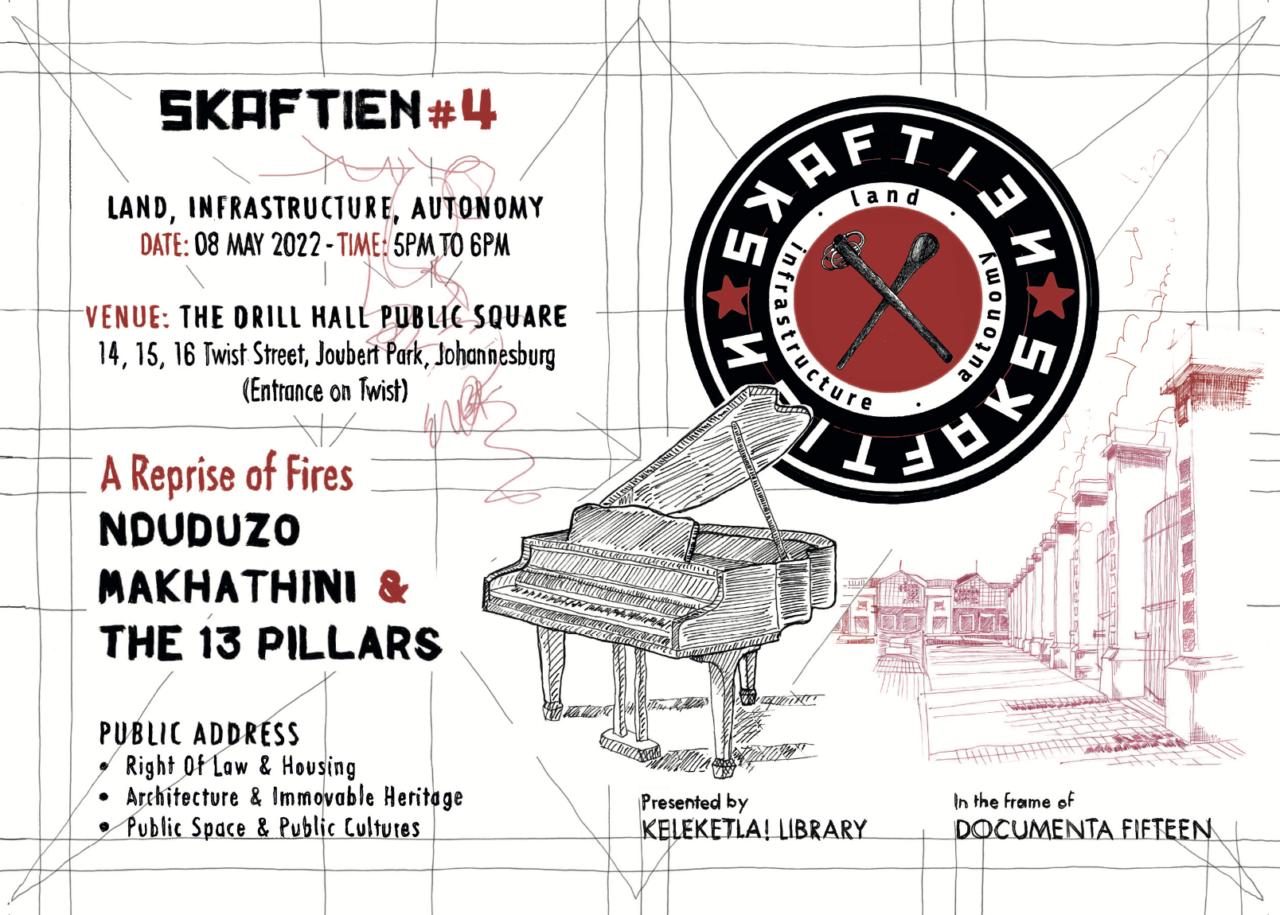

Keleketla! Library, Skaftien#4: A Reprise of Fires, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022, Courtesy Keleketla! Library

As the curtain falls on this essay, I feel we've delved deep into the resilient heart of Johannesburg's independent cultural scene, a gritty underdog grappling with the overpowering grip of the commercial art behemoth. Through my personal voyage and musings, we've celebrated the tight-knit community and rebellious spirit thriving within these underground sanctuaries, where artistic expression refuses to be tamed by the relentless market forces. We've also pondered the unsettling reality of our culture's exportation, leaving us as spectators to our own narrative. In this provocative mix, the concept of Parasitic Mutualism emerges as a disruptive strategy, a call to arms for artists to challenge conventions and ignite conversations. It's a clarion call to imagine a future where independent cultural production not only survives but thrives, injecting a much-needed dose of dynamism into Johannesburg's artistic tapestry and the broader cultural discourse.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory