Crafting a 'museum' worthy African art collection

Mary Corrigall takes a close look at the collecting patterns of three renowned public museums to discover which African artists enjoy institutional validation in New York, London and Paris. Do public museums carry as much power, since private art museums started driving exhibition programming and snagging the most sought-after works?

Installation photograph of Zanele Muholi Exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020, Photo by Christian Fregnan via Unsplash

Installation photograph of Zanele Muholi Exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020, Photo by Christian Fregnan via Unsplash

Of all the rhetoric employed by gallerists and art dealers to persuade someone to buy an artwork, the most convincing pivots on an artist’s work being acquired by museums. Unfortunately, in the context of selling contemporary African art, this tactic carries far more weight if the museum is located in a western art centre. Museum or institutional validation is seen as so vital that artists CVs or biographies almost always indicate which collections or institutions have acquired their works.

Given that most of the main international public and private art museum collections can be viewed online, art buyers are no longer have to rely on in-person encounters with works – which often never make it out of storage – but can nose about and see which African artists have garnered institutional validation. Interestingly –collections at public African museums are not available online.

If you had to build a collection - call it the ultimate African museum collection - based on the artworks produced by African artists that have been acquired by the Tate in London, MoMA in New York and say, The Centre Pompidou in Paris, which artists and works would feature in it?

A brief study of the works produced by African artists in these three most renowned museums in western art centres revealed, not unexpectedly, that the majority of the works were made by artists from South Africa. Egypt, Nigeria, Morocco and Ghana are ranked behind SA in 2nd, 3rd,4th, 5th place respectively.

Of the South African artists that are collected by all three of these world renowned museums are; William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Zanele Muholi, Guy Tillim, Marlene Dumas, Ernest Cole, Sue Williamson and Ian Wilson, who might not be known to South Africans as he forged his career largely in the US. Egyptian artists that have works in all three museums are; Sameer Makarius and Anna Boghiguian. Nigerian based, but Ghanian born, El Anatsui and John Akomfrah have works in these museums as does Morocco’s Yto Barrada and Mohammed Melehi. Algiers’ Jean-Michel Atlan, Cameroon’s Barthélémy Toguo, and Ethiopian born Julie Mehretu naturally also enjoy institutional validation by these museums.

You would need to be a fairly moneyed collector to snag a work by most of these artists, though with the South African photography based artists such as Tillim, Cole and Williamson you could secure a relatively affordable editioned work. South African photographic works appear to be collectable yet – apart from those works made by Goldblatt – are not highly valued on the art market. In other words, a ‘museum’ worthy collection might not always be one that would do well at auction.

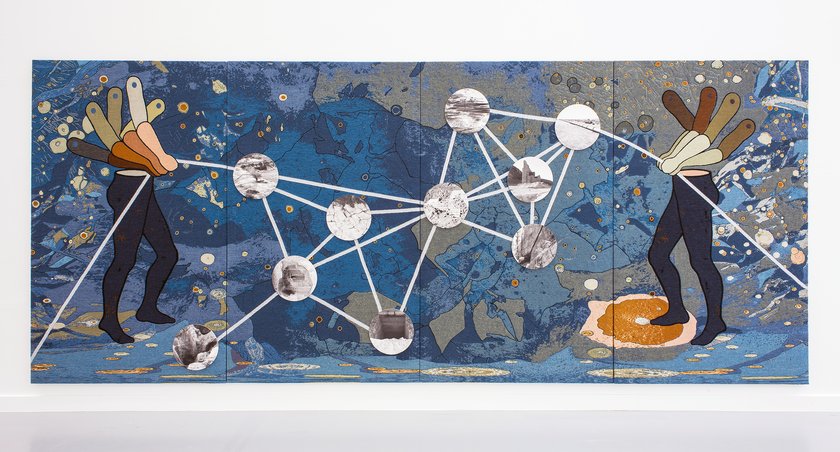

Otobong Nkanga, (1974, Nigeria), at the Centre Pompidou, The Weight of Scars, Photo credits: © Philippe Migeat - Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP, Image reference : 4N82267, Image presentation : l'Agence Photo de la RMN

Otobong Nkanga, (1974, Nigeria), at the Centre Pompidou, The Weight of Scars, Photo credits: © Philippe Migeat - Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP, Image reference : 4N82267, Image presentation : l'Agence Photo de la RMN

A number of the artists listed above - Dumas, Mehretu, Akomfrah, Toguo - and those that appear in two of these museums’ collections such as Robin Rhode, Candice Breitz, Moshekwa Langa, Otobong Nkanga, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Pascale Marthine Tayou, Sammy Baloji, Wangechi Mutu and Lubaina Himid are settled outside of Africa. This suggests that those artists more likely to enjoy institutional validation in western art centres are more embedded in them. Given the repeated commonalities between the works by African artists in the collections of the Tate, MoMA and Pompidou evinces a shared awareness among the acquisitions boards on which artists’ works should be collected. As such it appears that taste in art, even in the realm of museums, is as circular as it might be in the art market, where the same names keep reappearing and there are discernible waves of interest in certain artists at certain times. Call it herd buying mentality.

Why is it that museum validation counts for so much and should art buyers assiduously collect works by artists on whom they confer recognition?

One of the main reasons institutional validation is thought to carry so much influence is perhaps, ironically, due to the fact that museums are thought to be divorced from the commercial activities of the art world. Being at a remove from commerce, has situated institutions as objective purveyors of art and taste of it. As museum gatekeepers are thought to be harder to please their ‘judgement is seldom questioned’, suggests Don Thompson in The 12 million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art (2008).

Of course, the idea that museums are at a remove from art market may be somewhat of a utopian notion, particularly in countries where there are low if any government funding for acquisitions. This may partly explain why state-owned museums in African countries carry little influence in the market for contemporary African art - expanding their collection depends on collectors donating works but also on galleries and artists donating them. Brought to its knees, the state funded Joburg Art Gallery in that South African city participated in an online art fair last year, offering works by emerging artists for sale. On the face of it they appeared like any dealer. Did their backing add kudos to those artists?

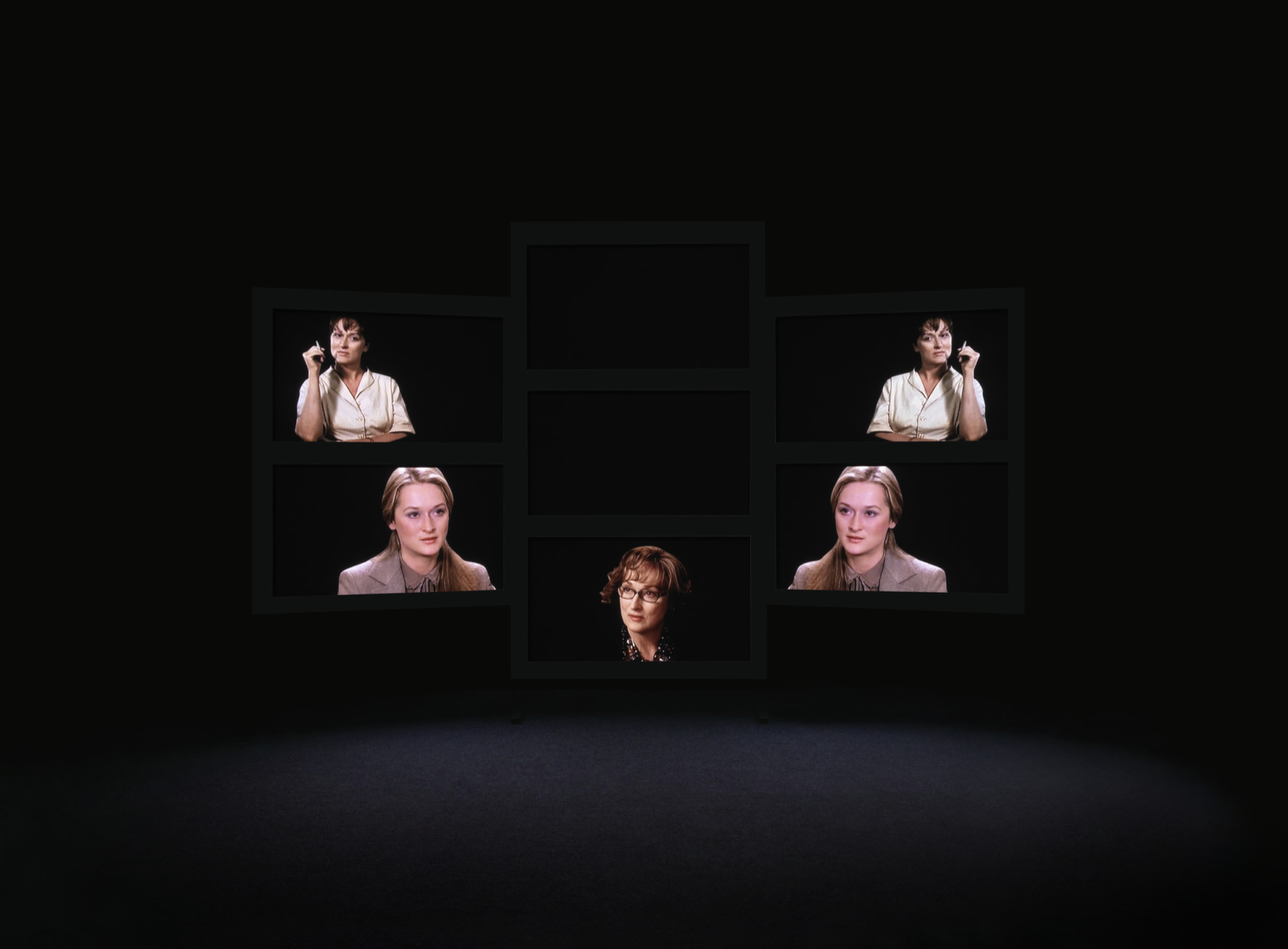

Candice Breitz, Him + Her, 1968-2008, Two seven-channel video installations (color, sound), 28:50 min. and 23:56 min, Credit: Gift of Outset Contemporary Art Fund, Copyright: Courtesy of the artist, Image from Museum of Modern Art website

Candice Breitz, Him + Her, 1968-2008, Two seven-channel video installations (color, sound), 28:50 min. and 23:56 min, Credit: Gift of Outset Contemporary Art Fund, Copyright: Courtesy of the artist, Image from Museum of Modern Art website

In the US where museums rely on private donors and acquisition boards can be populated by collectors with a vested interest in acquiring works by artists already in their own collections so as to increase their value, the notion of the museum as a veritable fortress of independent taste cut off from the art market doesn’t hold much water.

Of course, the proliferation of private art museums has seen collectors establish institutions to not only underscore the value of their collections and artists they support but also because they are as “passionate about art and this is how they want to spend their money” according to András Szántó, cultural consultant.

The proliferation of art foundations has worked towards driving up the price of art, with billionaires competing for desirable works for their quasi museums and it is in these kinds of spaces that the most prestigious exhibitions are being staged, according to Georgina Adam in The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum (2021).

As such not only are private museums making it difficult for public ones to acquire art – which is now more expensive – but sometimes, undercutting their programming too. This is chipping away at the status of public museums. In South Africa, the most exciting ‘museum’ quality shows are being staged at private art foundations. Take the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation’s recent Liminal Identities in the Global South, the first tightly curated African exhibition to bring African and South American female artists’ works into conversation.

Perusing through the recent acquisitions by the Tate, MoMA and Pompidou it is clear that they are not necessarily involved in ‘building’ new artists careers but rather collecting those artists who have been validated by the art market or other institutions already. As such they could not be looked upon as ‘market leaders’ where taste in contemporary art is concerned.

Pascale Marthine Tayou (Jean Apollinaire, dit), at the Centre Pompidou, (1967, Cameroun), Open Wall, 2010, Credits: © Adagp, Paris, Photo credits : © Philippe Migeat - Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP, Image reference: 4N94575, Image presentation : l'Agence Photo de la RMN

Pascale Marthine Tayou (Jean Apollinaire, dit), at the Centre Pompidou, (1967, Cameroun), Open Wall, 2010, Credits: © Adagp, Paris, Photo credits : © Philippe Migeat - Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP, Image reference: 4N94575, Image presentation : l'Agence Photo de la RMN

The red-tape and small budgets that public museums even in France - The Centre Pompidou’s acquisition budget was €2-million in 2018 - perhaps make it impossible for them to act ‘fast’ and buy an artwork on a whim – in the manner of the private art foundation. This might be to their credit – they aren’t slaves to the fickle fashions that seem to drive the art market and ‘taste’ is determined by a board rather than that of a single collector or his or her advisors.

Where does this leave collectors looking to collect works by artists who have institutional recognition?

Ultimately, a single acquisition by a museum or private art museum of an artist’s work isn’t sufficient – you need to establish consensus by a number of museums. At this point the works are likely to be expensive and outdated in terms of their ‘contemporary relevance’ and it will come down to collecting those that are of a museum quality – not every work by an artist with institutional validation is worth buying.

Corrigall is a Cape Town based art consultant, researcher and journalist.

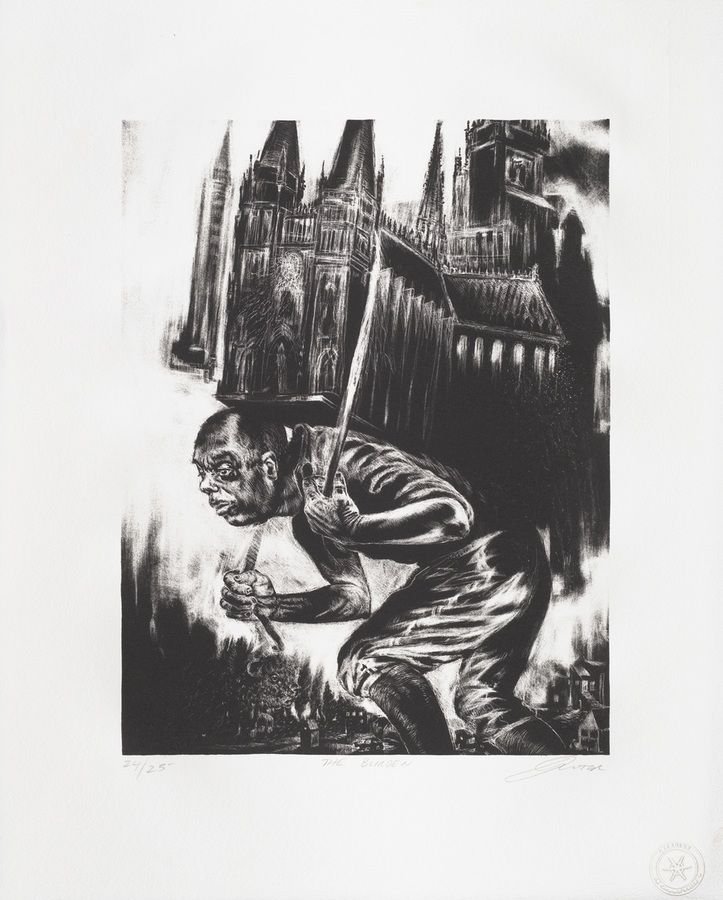

Collect South African Artists Featured in International Collections

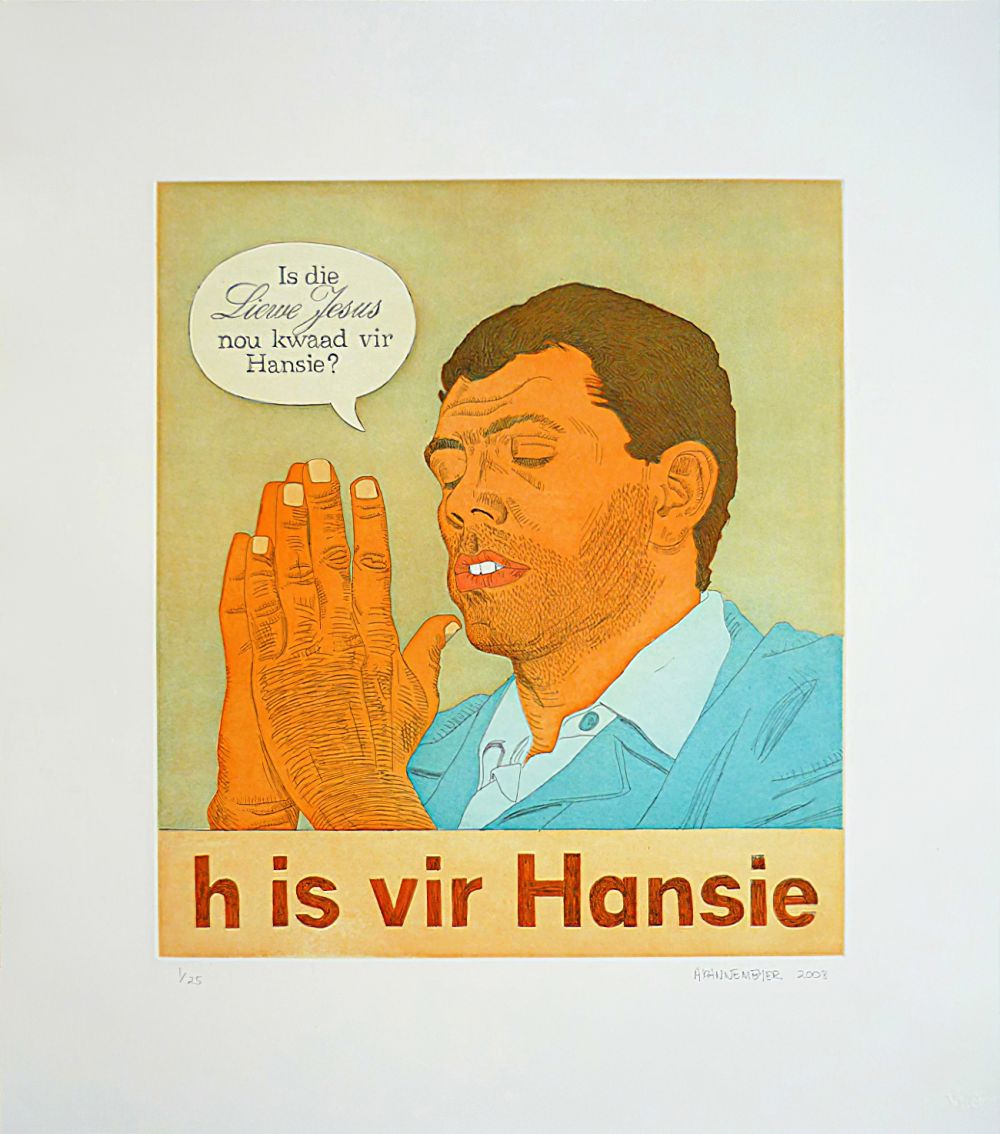

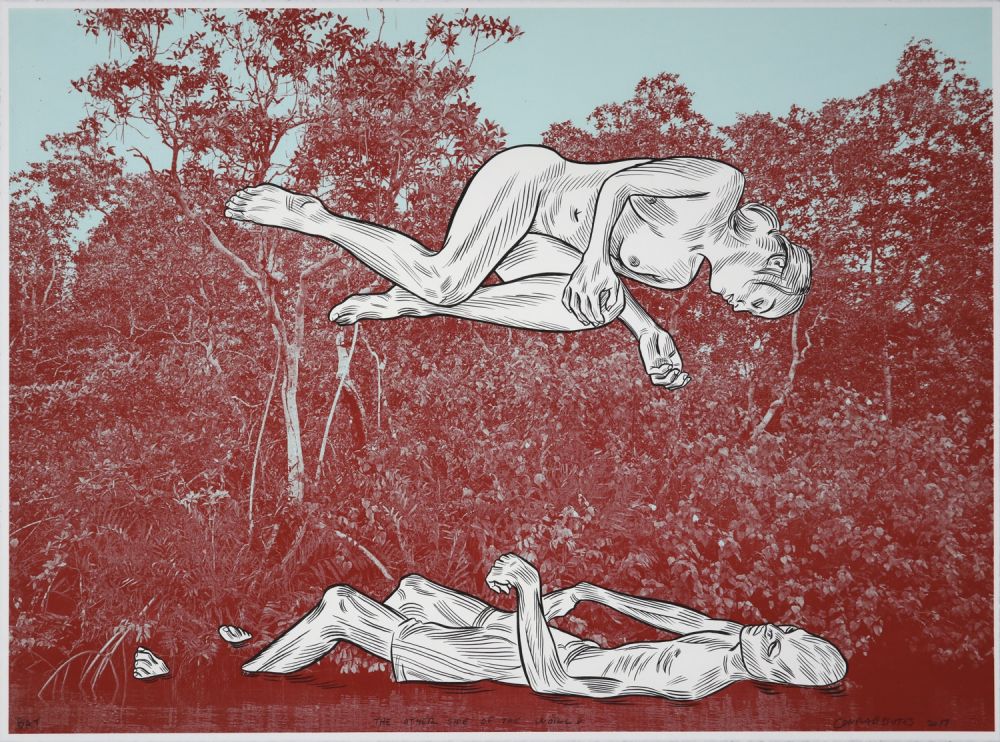

Diane Victor The Burden, Manière Noir Stone Lithograph, Edition size 25, 43 x 35 cm, R 9,000.00 ex. VAT

Enquire here

Diane Victor is a MoMA collection artist

Enquire Here

Gonçalo Mabunda, Christ of the new people, Metal scarps and ammunitions, 125 x 123 cm, R 178,750.00 ex. VAT

Enquire here

Gonçalo Mabunda is an artist in the Pompidou

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory