Corporate Art Collections get down to doing business differently

Covid-19 has forced curators of corporate collections to find new ways to keep art in circulation

-------------------------

Marieke Prinsloo-Rowe, Africa’s Fearless Thinker, commissioned by RMB

The transition to remote working kickstarted byCovid-19 has, perhaps unsurprisingly, impacted corporate art collections in South Africa. It has translated into a radical downsizing of office space, which has reduced the amount of wall space for art and also limited opportunities to connect the staff of a company to its collection or, more broadly, to art.

Corporate art collections are not static entities. They have grown and evolved with the changing fates of the businesses that support them, socio-political shifts and the evolution of the art market, which has lessened the initial role corporates played in the art ecosystem. This has forced curators to make adjustments, not only to the kind of works they set out to acquire, but other related programmes and their public interface via their collections and/or in-house galleries.

On paper, corporate entities are free to create their mandates but what do we, the public, the art fraternity, expect of those South African companies that hold large collections of art, essentially our visual history? There was a time when corporate art collectors sustained a small art industry and were a lifeline for many artists and small art dealers. What role do they play now that our art ecosystem has expanded exponentially and our dealers and artists are active in the global art market? Are they bound to do the work that our public entities can’t – acquire the works produced by our best artists in the country? Preserve our art history and educate the public about art? Should they be focussed on supporting emerging talent rather than the big names who are in less need of promotion? Should they play a role in job creation as per the state’s dictum for the creative and cultural industries?

‘Confrontation’, created by world-famous South African sculptor (of Italian descent), Edoardo Villa in 1978. Villa encapsulated the pain, defiance and anger from the Soweto student uprising in 1976 in a gigantic steel structure which became his largest non-commissioned outdoor work. ‘Confrontation’ has been fully restored and now takes prime position at RMB’s Think Precinct, courtesy of Boogertman architects who donated the piece to RMB when RMB took occupation of 1 Merchant Place in 1996

As with all issues that are related to culture, the answers are rarely straightforward. Even when some of the most well-known corporate collections were founded and decorating board rooms might have appeared a simple mandate - as Stefan Hundt, curator of the Sanlam collection has observed; "art in the workplace is rarely passively accepted".

Corporate collections in South Africa seem to have been established in waves, Standard Bank and Sanlam’s collections in the 60s, Sasol in the 80s. However, it was the dawn of a democratic dispensation in the 90s that persuaded several other corporate entities – MTN, Spier – to initiate art acquisition policies.

“There was a radical postmodern shift in corporate art collecting practice in South Africa at that time,” recalls Niel Nortje curator of the MTN collection.

“The aim was to mould MTN’s inventory profile into one that provided both historical and cultural depth and brought together reflections of South Africa’s divided past and multi-layered present in an attempt to re-contextualise South African art history while also supporting artists,” he adds.

The Spier collection was guided by less weighty ideas, viewing artistic expression almost as documents of varied lived experiences.

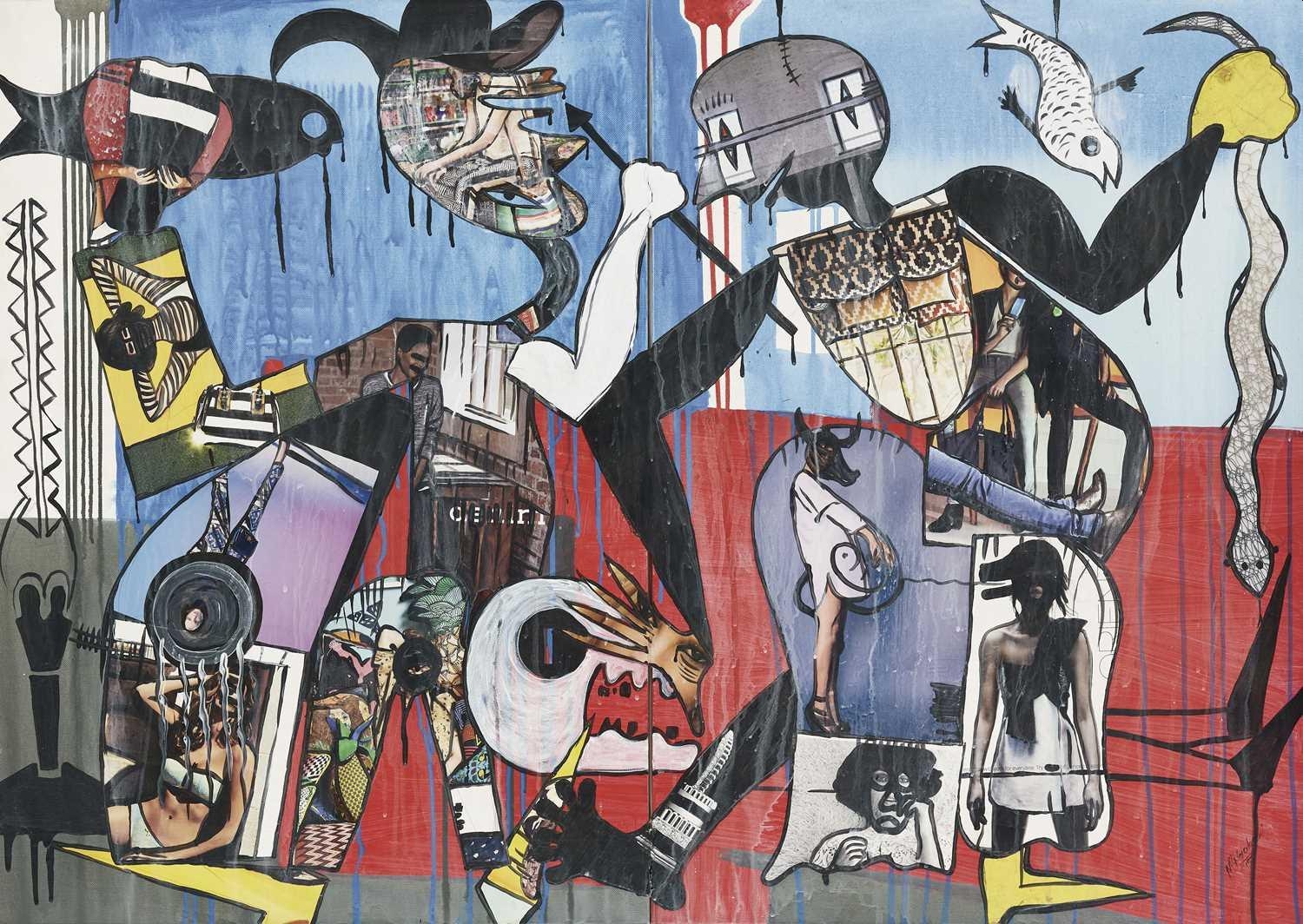

Blessing Ngobeni, Figures and Fish, 2015, acrylic and collage on canvas, 84 x 118 x 3.5 cm, a recent acquisition for the Sanlam Art Collection

“As a collection that started off in the early years of democratic freedom in South Africa it reflects the work of artists that were, for the first time, allowed freedom of expression. We weren’t guided by political or social themes, but rather we wanted to reflect the experience of South Africans in this process of transition and towards a hopeful future,” observes Mirna Wessels, director of the Spier Arts Trust.

It was a scathing article written by Elza Miles at the end of the 80s titled Kuns en die groot korporasies (Art and the big corporations) that set the Sanlam collection (and probably others) in a new direction, according to Hundt.

“The corporate art collections faired badly in her estimate and result in nothing more than self-aggrandisement and self-promotion. Public criticism such as this combined with the lack of an adequate budget for the purchase of works, put the Sanlam art advisory committee under some pressure to reassess the collection’s status and progress,” suggested Hundt.

This led to “a shift in consciousness amongst the committee members towards more contemporary artists and the realisation that there were serious gaps in the collection with regards to works by Black artists.”

The '90s also saw an interest in the investment value of the artworks in the Sanlam collection. This was due to “the company using funds acquired from policyholders,” according to Hundt.

The investment value aspect of works interestingly doesn’t appear to have been a guiding motivation for many of these corporate collections.

“We don’t buy only from a small group, and do not focus solely on emerging or established artists. We never buy with the intent to maximise on investment,” says Wessels.

RMB's corporate collection was “not built to have a definite monetary value, but rather one that would be true to the ethos of the business,” comments Carolynne Waterhouse, who heads the creative counsel at that financial institution.

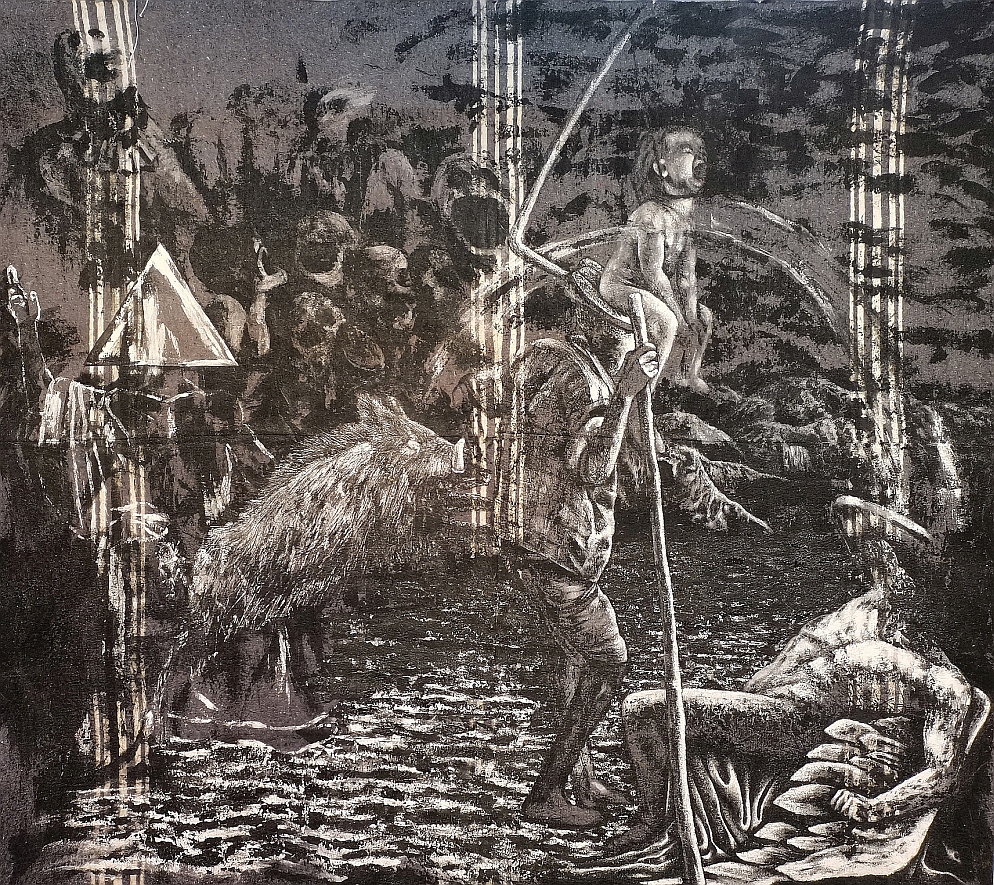

Thoka Frans, Go wa ke go tsoga, oil on blanket

This may have been the case for a number of corporate collectors, perhaps as there was little intention of selling works and realising their value in the secondary market – indeed most of the works that are sold off are those deemed to be ‘less relevant’. This has been the case for the First Rand collection – an amalgamation of the First National Bank and Rand Merchant Bank collections. Its curator Beth Van Heerden recently sold off a large collection of ‘botanical’ works.

“Tastes do change and the composition of our staff has changed and we have to look at art that appeals to our staff,” says Van Heerden.

However various curators responded to the shifts in South Africa’s society and political landscape, what seems certain is that corporate collectors provided a lifeline to artists and dealers until the mid-noughties when the country’s art ecosystem started to grow exponentially, due to globalisation, which allowed them to pursue opportunities in western art capitals, and a wider interest in art collecting locally. However, this has not shifted the importance of corporate collectors in the arts landscape.

“My opinion is that corporate collections are more important now, but primarily in their capacity as custodians of the works already in their possession. This is especially important if we consider the various challenges public collections currently face, mostly due to financial restraints,” says Cate Terblanche, Art Curator, Sasol Art Collection.

As collections have matured and a more buoyant art market has evolved, some corporate collectors have deepened their contribution via a variety of initiatives to support artists at different levels in their careers.

Certainly, Waterhouse, who heads the creative counsel at RMB, suggests that their support is in-depth and not only focussed on the visual arts.

“We support organisations across a variety of creative disciplines, to unlock talent and social transformation through the arts, through the RMB Fund/FirstRand Foundation. We fund beneficiaries to promote access to quality arts education and excellence in music, dance, drama, visual arts and heritage, with the goal of enabling young talent to participate effectively in the economy,” she says.

To some degree, it seems that the acquisitions process that curators were engaged in, naturally evolved into other initiatives to support artists.

“Over time the focus became increasingly centred on the various Sasol sponsorships, such as the Sasol Wax awards, the KKNK and the Sasol New Signatures Art Competition, which was first sponsored in 1990,” says Terblanche.

Thoka Frans, Moipolai Ga llelwe Sello Sa Gagwe ke, oil on prison blanket, a recent acquisition for the Sanlam Art Collection

For Spier "a holistic approach to artist support naturally evolved from our acquisition process. As a not-for-profit trust, our stated purpose is to provide career development opportunities for artists. This sourcing ecosystem came about in 2004 and led to the development of programmes focused on each level of artist career status,” says Wessels.

Have the collections taken a back seat? Particularly now post Covid-19 when office space is shrinking in the wake of remote working and the in-house galleries and display areas for exhibitions aimed at the public or staff were closed during the pandemic and became less vital spaces.

“We have resumed making acquisitions but these are few and far between. Some from auctions and occasionally from a private sale. In total, some 10 works over the last three years,” says Hundt.

Sasol’s collecting strategy remains tied to the Sasol New Signatures competition, says Terblanche.

Before Covid-19 Sasol “had a very active programme of art events at Sasol Place, which included our own version of ‘First Thursdays’, where we had walkabouts and short lectures throughout the day.”

The pandemic has seen Sasol make use of virtual platforms, particularly for the New Signatures.

“It’s been a matter of necessity, but I’m not totally convinced that the virtual arena is the optimal way to go, definitely not as a stand-alone approach. There is something to be said for viewing art in person, art is after all an experience.”

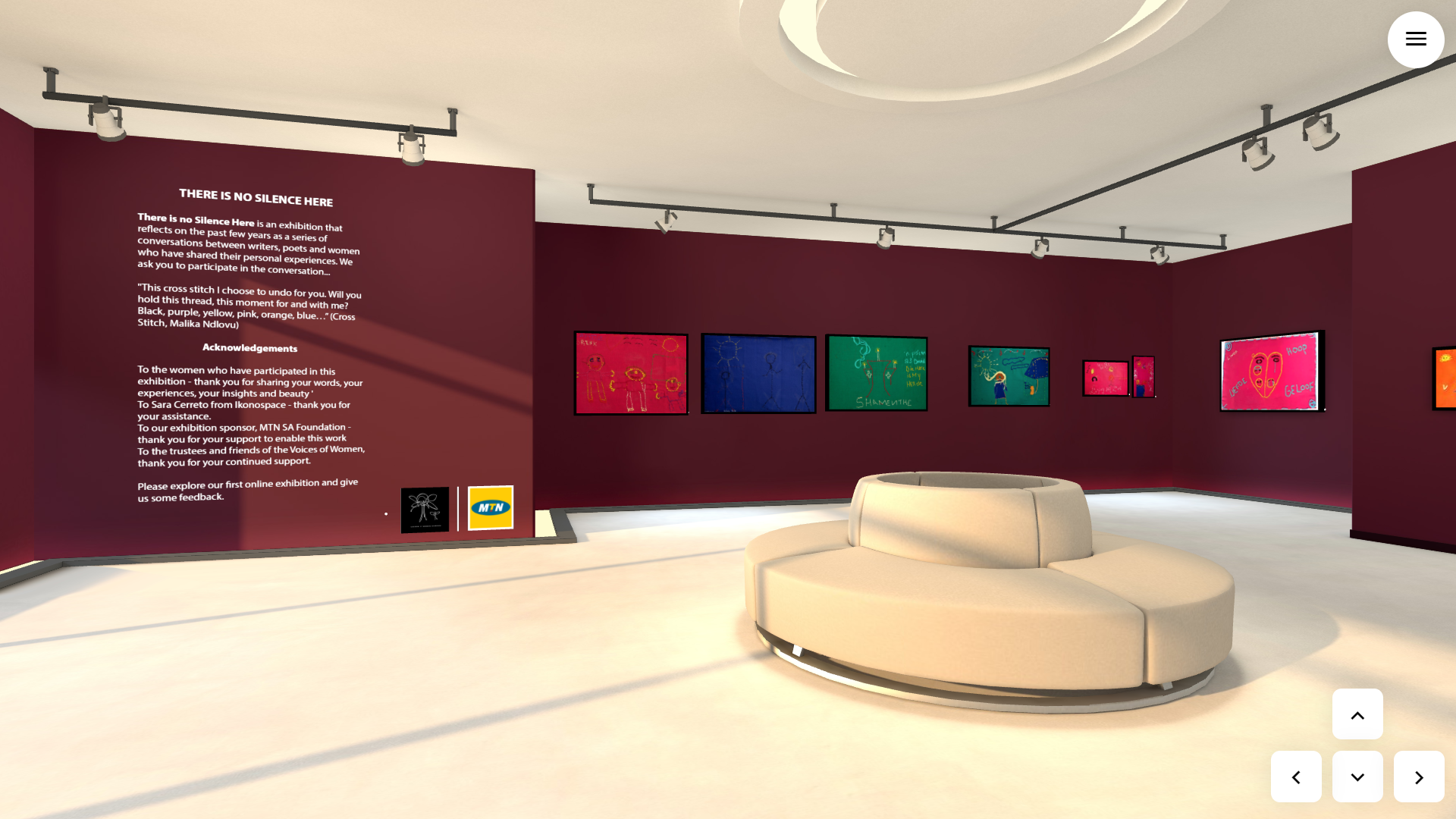

Covid-19 saw MTN invest in virtual platforms such as the UJ Art Gallery Moving Cube (https://movingcube.uj.ac.za/), Imbali’s Adventuring Into Art website (https://imbaliartbooks.org.za/) and their own virtual art gallery MTN | making a difference, which Nortjie says has "exponentially increased our ability to share MTN’s Art Collection with the public".

Educating the staff about art in the post-Covid world initially proved tricky. Before Covid-19 Van Heerden strategically used a space that led into the staff canteen to stage exhibitions not only of works in the collection but also to allow art to be sold. Artist Proof Studios for example staged an exhibition in this space.

Virtual exhibition staged by MTN during the pandemic

Virtual exhibition staged by MTN during the pandemic

“All sales were conducted through them. We would pay for the opening night event. The idea was that the staff would be encouraged to buy some of the works and start their own collections,” says Van Heerden.

Meeting rooms, foyers and co-working spaces have become the focal spaces for the First Rand art collection in the wake of remote working, says Van Heerden.

Conversely, new opportunities for First Rand to exhibit art and support artists also opened up through Covid-19 when they turned some unoccupied space on the ground floor of the FirstRand campus in Sandton into a pop-up gallery they dub Art & About.

There are other ways for the art in corporate collections to circulate – such as through loans to institutions or other businesses – FirstRand have loaned works to the Rand Club among others, according to Van Heerden. With around 5000 artworks in their collection, keeping the artworks in view is challenging.

“We are not buying art for the storeroom,” she quips.

- Corrigall is a Cape Town-based art advisor, journalist and independent researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory