After Contemporary Art

- by Timothy Gawaya

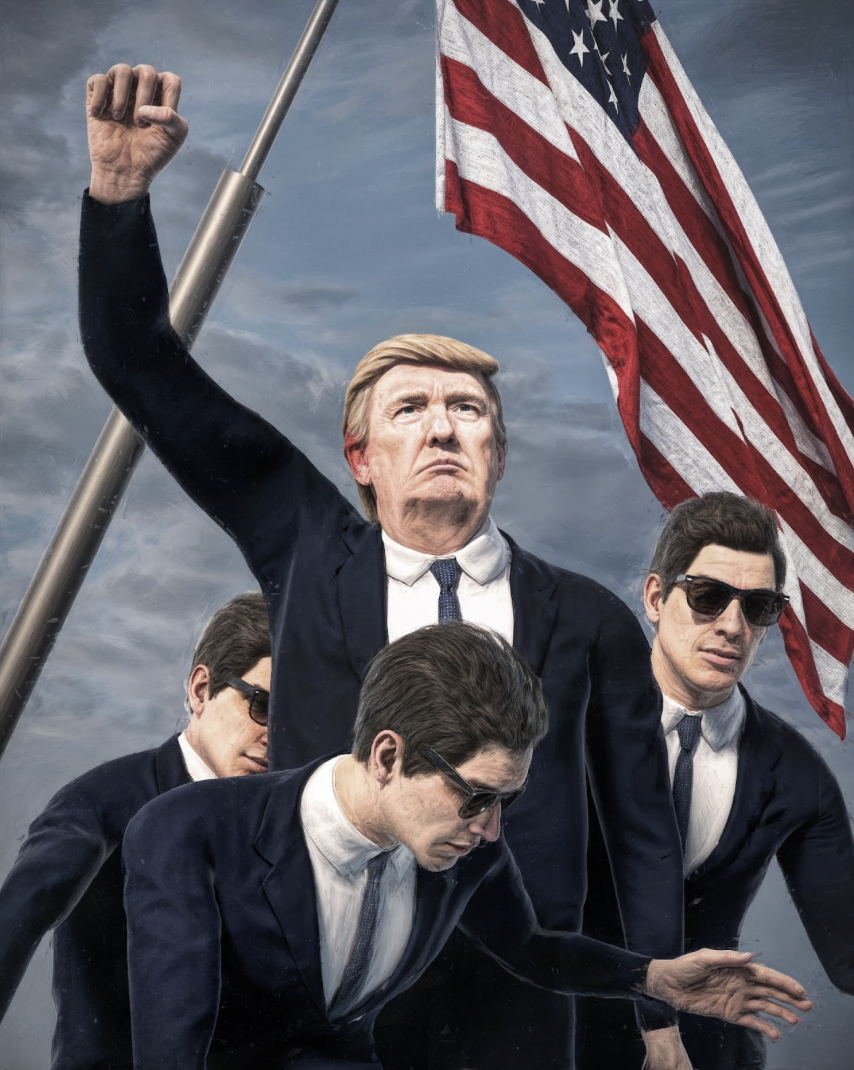

‘BULLETPROOF’ by Beeple (Mike Winkelman). 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

The days following Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential victory over Hillary Clinton can only be characterised as a headless frenzy to make sense of the incomprehensible. Clinton was the guaranteed victor by the most reliable estimates, facing someone seen as a renegade outsider. Trump was too chaotic and beyond the pale of respectable politics – hardly a statesman, he embodied the kind of doomed spectacle we’ve come to expect of politics. The New York Times forecasted Clinton as the likely candidate by a substantial margin based on pre-electoral polls, while the reputable FiveThirtyEight polling model predicted the likelihood of Trump winning at a meagre 28.6% to Clinton’s 71.4%.

Something similar unfolded following President Joe Biden’s exit from the 2024 campaign trail and subsequent endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris and her running-mate, Tim Waltz. The Harris-Waltz platform, a relatively new player in the game, performed somewhat well despite its infancy, quickly raising a reported $1billion from donors, and a series of celebrity endorsements from the likes of Taylor Swift, Beyonce, and Charli XCX. Although beset by a number of controversies, the Harris-Waltz campaign fared better in the public eye in contrast to the weird and eerie theatrics of Trump and his VP pick, J.D. Vance. Brimming with conspiracy, the Trump-Vance campaign bumbled and dropped the ball at every turn, while major polls predicted a Harris win by a slight margin. Kamala is brat, after all.

In both instances Trump was able to bypass the logic of keen observers. His 2016 victory was seen as an aberrant event, a rupture in the order of things, non-sensical to the extent that it could not be intelligibly grasped within prevailing discourse. If politics is to be understood as a legible system, then Trump appeared to evade its reasoning – or perhaps he appeared to exist outside its domain as a para-system to be accounted for and incorporated into a rational framework.

‘He Will Not Divide Us’, 2017-2021. Installation piece by LaBeouf, Turner and Rönkkö. Courtesy Luke Turner.

‘He Will Not Divide Us’, 2017-2021. Installation piece by LaBeouf, Turner and Rönkkö. Courtesy Luke Turner.

The art world unsurprisingly offered swift responses to Trump’s initial victory, a method of quickly patching and making sense of the discontinuity inaugurated by the Trumpian era. A notable piece was by the artistic trio comprising actor Shia LaBeouf, and artists Luke Turner and Nastja Rönkkö. Titled ‘He Will Not Divide Us’, the project aimed to counter the divisive rhetoric associated with Trump and the Republican Party under the controversial, now iconic ‘Make America Great Again’ banner. The participatory performance, split across several locations, encouraged audience members to utter the phrase, ‘He Will Not Divide Us’ while being live streamed to a separate website. As a representative response from the field of contemporary art, the performance served as a “show of resistance and insistence, opposition and optimism, guided by the spirit of each individual participant and the community.”

The message is clear enough: Trump, to the artists, and for contemporary art at large, represented a splitting of things as they stood. The game had not only changed, but entirely new coordinates had been introduced without prior warning. Contemporary art, already a highly politicised arena, had to contend with an occurrence that operated against the day. Moreover, the aesthetics of the Trump campaign carried a highly memetic register that rivalled the boldest excesses of modern celebrity – a feature that boosted his two wins and lent his 2020 loss to Joe Biden a rather tragic aura that ultimately fed the events of January 2021 when his supporters staged an insurrection.

Contemporary art is nothing if not a theatre of critique; its value is dependent on the ability of its actors and practitioners to stage (sometimes self-annulling) appraisals of art as an institution inextricably bound to flows of capital. In its global sense, as bound to transnational capital flows, contemporary art is not only art that is made today but an ideological paradigm: art’s critical element is its selling point. If the contemporary is seen as the confluence of rational free-markets with the rhetoric of political liberalism and democratic rule, then contemporary art is the agora or public space in which this confluence is interrogated.

History is neither cyclical nor a flat circle but a downward spiral. There was never any fun to be had. For many in the art world, Trump’s reelection marked a broad shift in an already fraught global political order, a confirmation that the centre had come apart. 2024 was a pivotal election year across the globe, with definitive electoral processes occurring in the United Kingdom, South Africa and India among many others. Grasped as a whole, traditional politics managed to scrape by in the face of heterodox, right-leaning populism. France’s political landscape trembled in the wake of a surging reactionary wave, where the National Rally (formerly the National Front) crossed over into the mainstream after decades of existing as a bothersome outlier. Although a coalition of left-leaning parties was able to secure a majority, edging out the National Rally by a hair, this could only be considered a minor success, an ominous refrain in the discordant symphony of an altered global order.

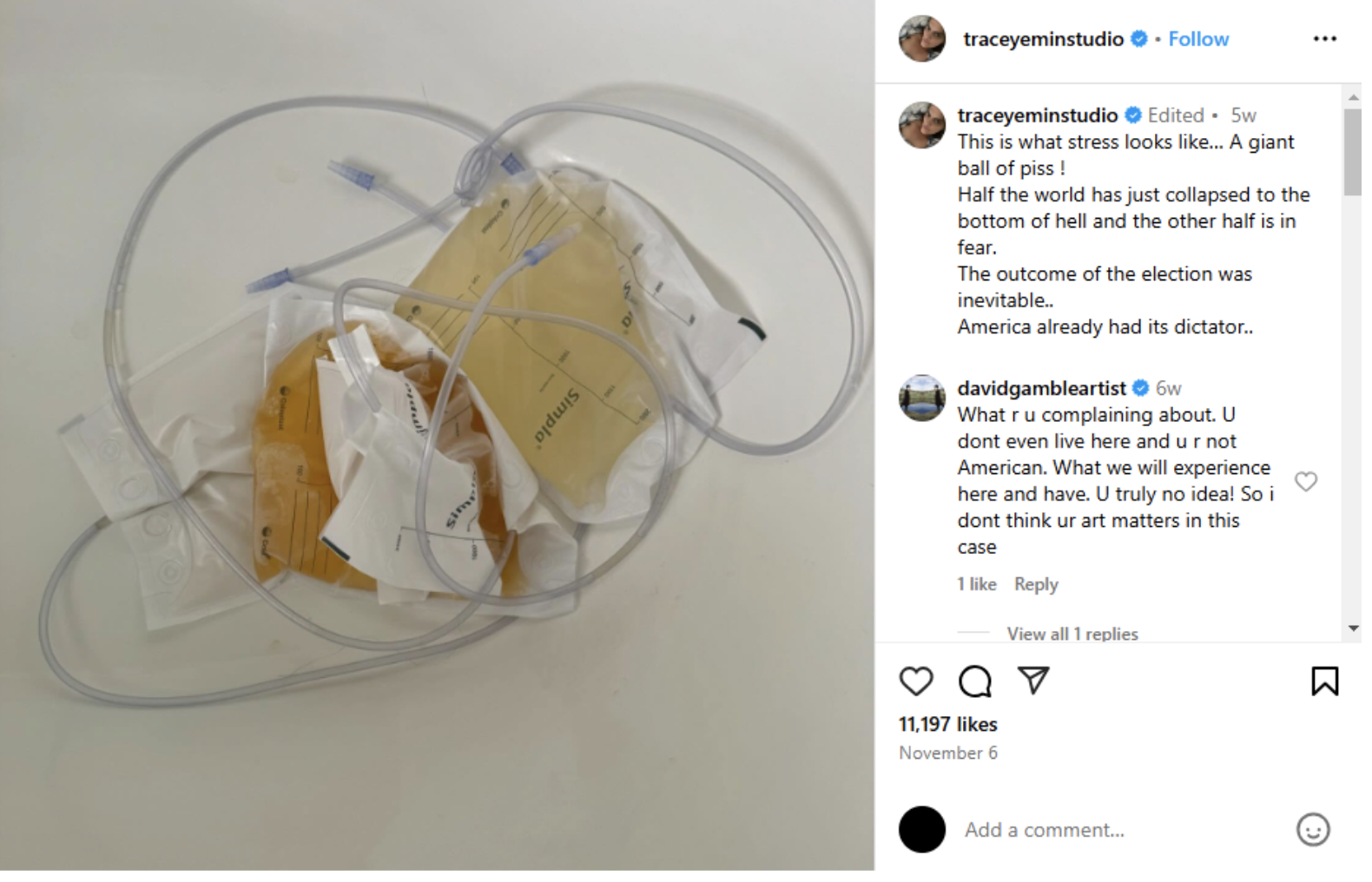

Instagram post by artist Tracy Emin, November 2024. Screenshot by author.

Instagram post by artist Tracy Emin, November 2024. Screenshot by author.

With a second Trump administration in sight, contemporary art is gearing to stage another four years of oppositional optimism to counter the Trumpian moment, perhaps broadly typified as a suspicion of the currents of political liberalism. Indeed, a coterie of notable and widely acclaimed figures, such as the exiled Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and British conceptual artist Tracy Emin, expressed their dismay at the results of the 2024 US presidential election. This came on top of rigorous support for Kamala Harris by high-profile artworld figures like Jeff Koonz and critic Jerry Saltz.

If greater politicisation is indeed possible at this critical juncture we may witness an increased reflection on political sovereignty and autonomy in the art field. However, this must come to grips with the broad disintegration of the liberal project in many facets of existence. And if there’s anything to be gleaned from the highly publicised purchase of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian by a crypto mogul who recently donated $18 million to a Trump-backed venture, it’s that all gloves are off: contemporary art’s sacral claims to progressivism cannot compete with the profanations of crypto-bros, our tech overlords and proto-Caesarist political candidates blitzed on billionaire finance.

What should follow is an aesthetic disposition weary of the (often ineffective) register of resilience, resistance and opposition that defangs art of its edge, masquerading impotence behind stultifying moral appraisal. Our pervasive sense of meltdown should be consonant with a libidinal politics of decline, and young African artists are already beginning to pick their teeth with the remains of the day. A standout exhibition from the preceding year was Cape Town-based gallery Vela Projects’ Kash Out, presenting works by South African artist Boytchie (aka Phillip Newman). Division is neither denounced nor remedied in the joyfully macabre Schemin (2024) or matter-of-fact Muney Up (2024).

My Precious (2024) by Boytchie, copyright Vela Projects

Those of us who unfashionably cling to the notion of an avant-garde recall its origin in the French term for ‘advance guard’: why oppose when you could always pierce through? For African artists, intimately familiar with landscapes marred by decline and uneven centres, contemporary art’s self-cannibalisation is beatifying. It’s been two years since Barbie (2023) and Oppenheimer (2023) showed that apocalypse can be pink, bubbly and plastic. Have you heard of Nano Le Face? He’s our Warhol; he’s like if Hieronymus Bosch had his heart broken by a Constantia girl with a ludicrously capacious handbag.

Nano Le Face, I don't wanna be real with you rn, R2,300.00 ex. VAT, buy on Latitudes

Nano Le Face, I don't wanna be real with you rn, R2,300.00 ex. VAT, buy on Latitudes

The question of contemporary art’s instrumental value in effecting political change will have to contend with what appears to be a broad rejection of progressive politics. The subject of what, if anything, arrives after the contemporary becomes paramount to the art field at large. Is such a revaluation of values feasible beyond the contemporary as a paradigm rooted in morbid self-reflection? This remains to be seen. For now, and the foreseeable future, contemporary art should perhaps heed those immortal words of W.B. Yeats:

…And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Author

Timothy Gawaya is a writer and doctoral researcher at the University of Pretoria. His primary research interests include philosophy of art, digital aesthetics, and modern and contemporary art.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory