The Ongoing Moment: The Muse of Music: South African artists inspired by sound

- by Percy Mabandu

Latitudes is pleased to introduce artist, writer and the author of the book, Yakhal'inkomo - Portrait of a Jazz Classic, Percy Mabandu. In this improvisatory essay, Mabandu tracks an ongoing sighting of musicians caught in the act of performance by a succession of artists across the space time continuum of South African art.

Sam Nhlengethwa, Tribute to Lemmy 'Special' Mabaso, 2002

Sam Nhlengethwa, Tribute to Lemmy 'Special' Mabaso, 2002

Our art history has been subject to an ongoing moment; a perennial communion of artists with their eyes trained on the marvel and metaphor of musicians in performance. Their work captures the ongoing moment as a motif marshalled across time and media, form and feeling. Think of the ongoing moment as an act of visual witness, a graphic invocation of forces beyond music as it inspires the act of art making.

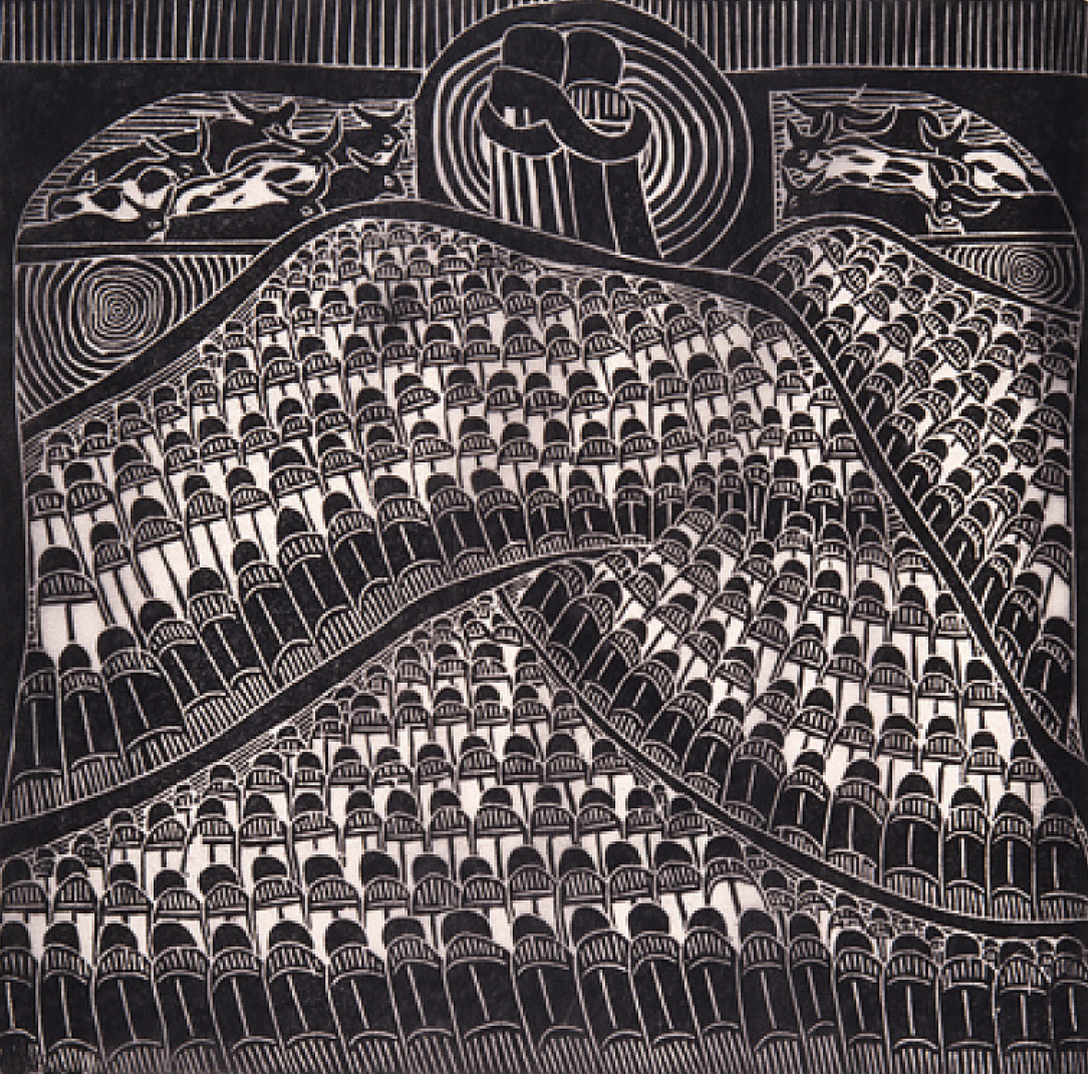

It’s an act of witness not to be confused with music as it features in the work of artists like Azaria Mbatha; artists with a propensity for depicting crowds and hordes of people. These are artists whose work triggers sounds of murmurs and hollers associated with crowds and choirs.

The musical moment in Mbatha’s work is implied and not represented. The artist hardly ever points us to the singing congregation or gathering; he relies on our own insight as cultural insiders to hear it through familiarity with the depicted scene. To look at Mbatha’s linocuts is to consent to being triggered to remember a sound. Think here of works like Exodus (1965?), Royal Wedding (1983) or even a work like, The woman who loved and was.../Innocent from accusation (1965).

Azaria Mbatha, The Royal Wedding

Azaria Mbatha, The Royal Wedding

Mbatha, and many of his peers, was educated in missionary schools and art projects that were obtained alongside the evolving Christian church in Southern African. This is why they derive much of their motifs from biblical themes. This is to say, the work of artists like Mbatha are a visual dimension of the sounds of the black church. The images they create are not unlike the hymns heard in the choral tradition of the black church. We should therefore consider, or speculate that the art of creators like Mbatha, et al, as a kind of whimsical genesis of our ongoing moment.

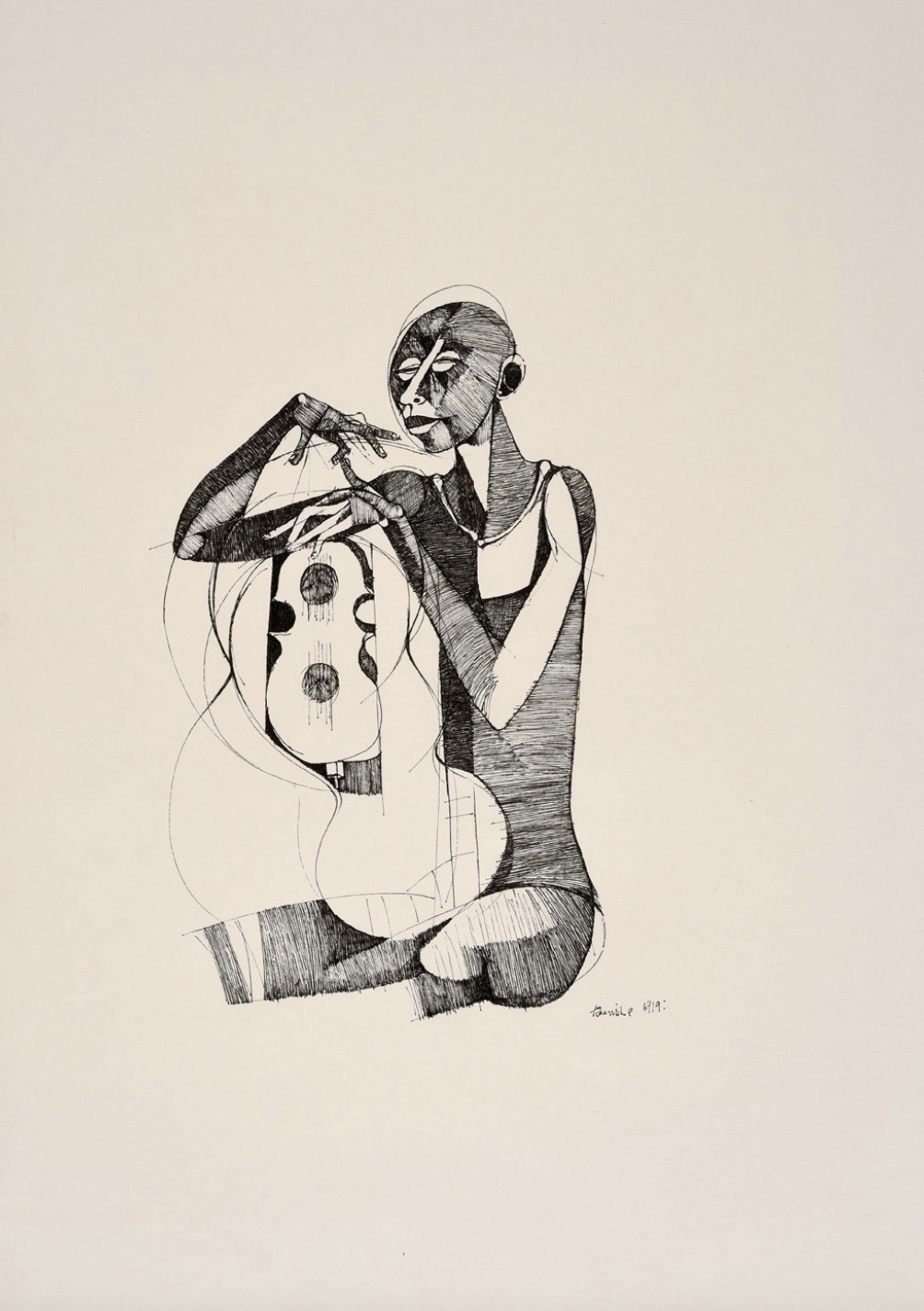

Moving from this speculated origin, let’s imagine the musical moment has its next random station in the life and work of Dumile Feni. Let’s move from writer John Berger's proposition: that those who “draw do so not only to make something visible to others, but to accompany something invisible to its incalculable destinations.” Therefore, the drawn line in Feni’s work is important “not because [they] record what [he] has seen, but because of what it will lead you on to see.” Berger’s suggestion here is aptly relevant because of Feni’s tendency to create or draw just enough for his viewers to get a message of his form, like suggestion, and not a complete image as such.

Dumile Feni, Untitled (Man and Guitar), 1969

Feni works like a musician would play, quote or code a half of a melodic line from another's familiar composition to make a musical statement. Think of something akin to pianist Andile Yenana riffing a line from a Musa Manzini tune, La Malinga in his own solo on Mhlekazi’s Dance. This similarity in Feni’s process with music making resonates well with what Berger points us to when he says, “Drawing is as old as Song.”

Feni, to be sure, presided over a creative practice that owes as much to jazz music as it does to liberation politics and art history. His friend and photographer, Omar Badsha has spoken about how Feni had more musicians as friends than he did artists. Go Figure! This may explain why Feni has created such a great number of drawings depicting musicians over his career. For instance, in 1969, the year after he went into exile, Feni created a number of stunning works depicting musicians in performance. Among these is a drawing of a cello player rendered in ballpoint pen on paper. Feni’s cellist is strident with his head bent as though peering at the sound issuing from his instrument. At the feet of the figure, the bottom of the drawing, Feni inscribes the words: In putting the Broken pieces together some of us may find peace, 1969.

In the same year, Feni created another remarkable drawing titled Flute Player. The work, created at a time of dark uncertainty, would later be donated to the constitutional court art collection by Judge Albie Sachs. Flute Player bears a motif that defines much of what we think about when we think of the ongoing moment of music and modern art in South Africa.

Dumile Feni, Flute Player, 1969

Shop works on Latitudes that make you want to move

Nine years ahead of Feni, the idea is expressed in a Peter Clarke oil on canvas painting, Boy with Flute aka ‘Flute Music’ (1960). Clarke gives us a defiantly colourful scene. His flute player is a young black boy in patched-up shorts walking through an overgrowth of grass and calla lilies in full bloom. His bright blue shirt is complemented by the coral coloured ground and mud walls of the lively village houses. These are cleverly composed to divide the foreground and skyline of the picture plane. Clarke paints a song in celebration of life during a year marked by death in the Sharpeville massacre, inaugurating an era often referred to as high apartheid.

Clarke’s Boy with the Flute has never been seen with Winston Saoli’s The Flute Player (1991), and may well be the same person. Saoli’s The Flute Player is a mixed media on paper. The figure appears as a strident man stalking through a moonlit dreamscape in improvised modern traditional African dress. The boy’s shorts are now Zulu mine workers’ patched-up trousers. He pairs them with an animal hide throw and feathered cap. Here then, we can speculate the expectant melodies of hope from the early 1990s political moment.

Peter Clarke, Boy with Flute

To ensure we do not lose important landmarks in the undertow, our thinking about this ongoing moment must also include Andrew Motjuoadi’s pencil on paper duet, Flute Players circa 1965. This is an artwork that is echoed by various contemporaries as penny whistler. It’s an ode to the penny whistle as an instrument that defines the itinerant, migrant spirit of early modern black life in South Africa. An era when many natives made the transition from rural to urban life. The penny whistle was the central identifying feature of Kwela music of the 1950s. A popular genre of street music and precursor to what we think of as jazz rooted in South Africa. To “Kwela” means to climb in the Nguni languages; like workers who “kwela” or climb on to the back of a truck, or catch a train ride en route to the farming fields or the mines of the reef. So, Kwela music is migrant worker music; in the sense that migrancy is the generative force of modernisation and urbanisation on our subcontinent.

It’s possible that of all the South African artists often referred to as the black modernists, none has paid more attention and tribute to musicians in performance than Ephraim Ngatane. The painter has produced a prodigious body of work with an admirable commitment to the spectacle of musicians in performance

Ngatane’s work is defined by the riotous roar of life and colour rivalled only by the bursting, bustling life of the township existence from which his subject was culled. He marvellously bore witness to myriad moments of musicality in everyday instances, and in ceremonious circumstances. Ngatane’s oeuvre makes a list of the ongoing moment: The Penny Whistler, 1969, is a seated solitary figure blowing his instrument. In another piece titled Penny Whistler, also a seated figure, the figure wears a hat and a jovial mood. Then there are various depictions of a standing Penny Whistler, in a white coat and khaki pants, or in a white T-shirt and blue trousers. In another scene, The Penny Whistler is a roaming musician in a Magenta jacket and a grey Irish newsboy cap. He is walking down a blurry street in a sea of colours that invoke his melodious song.

Ephraim Ngatane, Penny Whistler

Ngatane has also captured moments of musicians as street groups or bands, think of the Kwela Boys (Penny Whistlers) in 1967 painted in blues, browns and Ochers; or an exploration in pastel colours, Two Penny Whistlers in 1970. Then there’s a yellow ochre picture plane with a floating trio of dancing penny whistlers in whites and blues rendered with brisk gestural lines and strokes. In this way, to say you have seen “the penny whistlers” by Ngatane is to say nothing. To be meaningful, you have to describe the actual work; the viewer is challenged to wrestle with specifics, to name their encounter with intimacy. Otherwise, one’s report of Ngatane’s floating scene may be confused for the same moment as the work of another artist; like Gerard Sekoto, as The Penny Whistlers in 1967.

After all, even the king of kitsch, Vladimir Tretchikoff was touched by the ongoing moment too. In 1965, Tretchikoff painted his own Penny Whistlers. It would be published as a print by his British publisher. The portrait in the trio portrayed Cape Town Street musicians, the Kwela Kids: Robert Sithole, Isaac “Duke’ Ngoma and Josh Sithole, a band of two penny whistlers and a guitarist. The image’s reproduction became one of the ten best-selling prints of the year in the United Kingdom. It was also the first picture depicting African people to make its way onto the British best-seller list.

We can think of this as one the earliest tributes to actual identifiable musicians in the genre. It’s a tradition that carries on in the contemporary world through the work of artists like Sam Nhlengethwa. His seven colour lithograph, Tribute to Lemmy 'Special' Mabaso (2002) may be a throwback to a musician from an earlier era; it continues an ongoing moment with fighting verve.

The flute and the penny whistle share a subaltern resonance with the guitar as an ideal instrument of itinerant musicians. The acoustic guitar enjoys a unique status in working class black life in the land of the fallen rand. Maskandi music, which has allowed for the unique Zulu style playing guitar is indebted to the stringed instrument, as much as Kwela owes to the penny whistle.

This has inspired works like A Malay Boy Playing a Guitar, with a Duck in the Background by Maggie Laubser created in pencil on paper. Later, in 1956, Laubser painted a Boy Playing Guitar as a faceless farm worker or rural man sitting under a tree. The character may be the same one painted in 1968 by George Pemba as an urbanised Guitar Player. He may also be one of the monstrosities that populate the tortured picture planes in the troubled imagination of Blessing Ngobeni.

Maggie Laubser, A Malay Boy Playing a Guitar, with a Duck in the Background

The ongoing moment, which in earlier modern art history was expressed with abstracted faces of unknown everyday people is expressed as tributes to icons and celebrities in contemporary art. The photograph, as a social media post or reel, has drained the moment of its mysterious charm, trading it for potential ubiquity of the rhizome. The ongoing moment, which once traded on special singularity with each sighting, now reaches for a state of spectacular virality.

Shop works on Latitudes that make you want to move

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory