Not Setting History In Stone

“Marble Dust hovers in the air and collects into piles on the ground; it is both solid and ephemeral, as are our bones.” – Talya Lubinsky

Talya Lubinsky, a South African artist based in Germany, was one of seven artists who participated in Chelsea Selvan’s online exhibition, What shapes us? Makes us? Guides us? as part of Latitudes Online’s curatorial programme – CuratorLab.

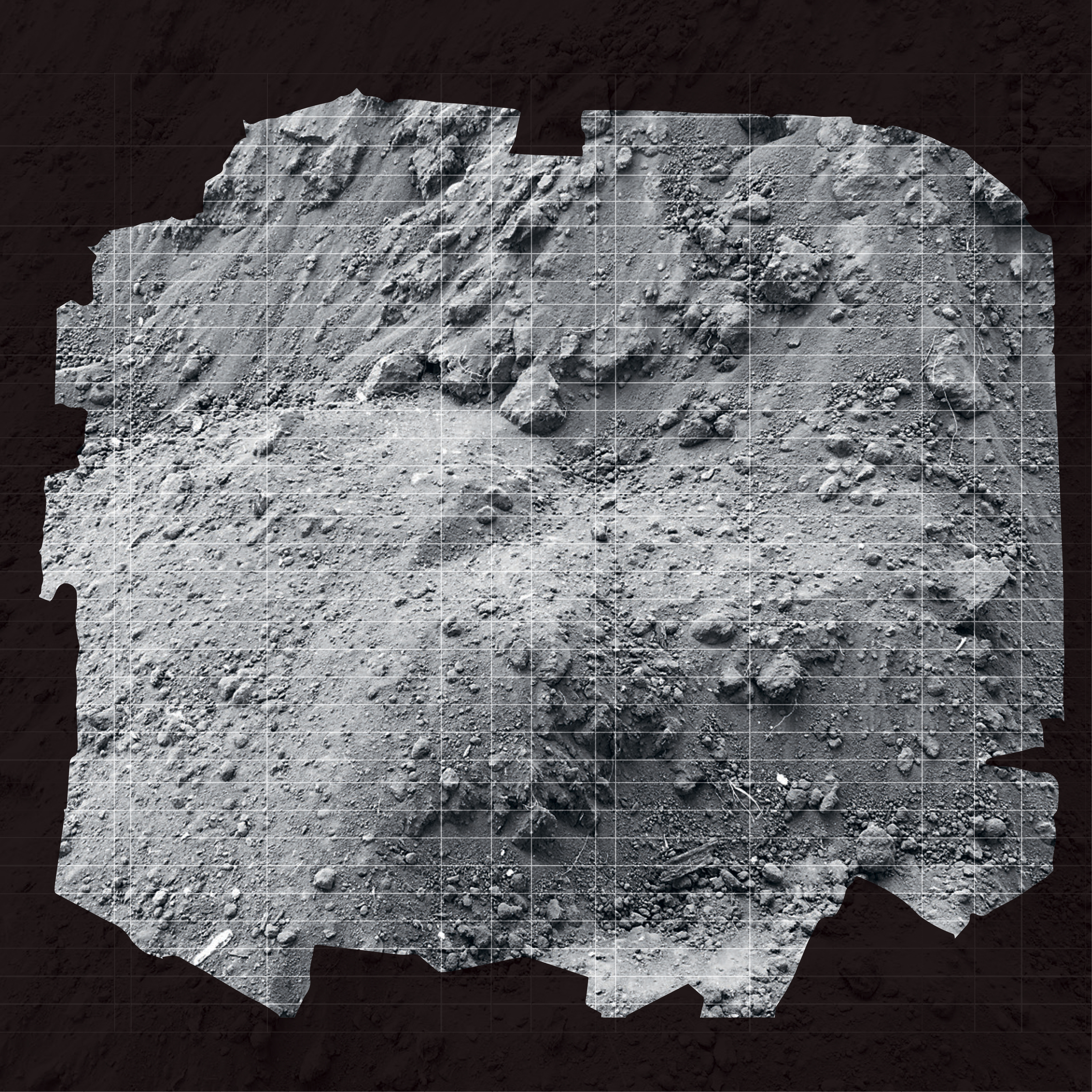

During her residency at Kuenstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, from 2019 – 2020, Lubinsky worked towards a sculptural abstract installation titled Marble Dust. Her installation contemplates the material relationship between permanence and disintegration embodied in memorial sites and the landscapes of cemeteries.

Research on cemeteries in South Africa led Lubinsky to a cemetery in the Mamelodi township, North of Pretoria, where black political prisoners who were hanged by the Apartheid government in the 1960s were buried.

“They were buried as paupers, with no gravestones. The remains of these murdered activists were exhumed between 2016 and 2019 and returned to the families of the deceased. After almost 60 years, the bones have disintegrated to the point that they have turned to dust, indistinguishable particles dispersed within the earth. In some cases, it is piles of earth, dug up from the grave sites that is placed in coffins and returned to the families,” Lubinsky explains.

For Lubinsky, this process of digging up and returning something that is almost fully disintegrated, is a powerful symbol for that which has been lost. The impossibilities of reconstitution and restitution on the one hand, and the profundity of the gesture of return as recognition of injustice, on the other.

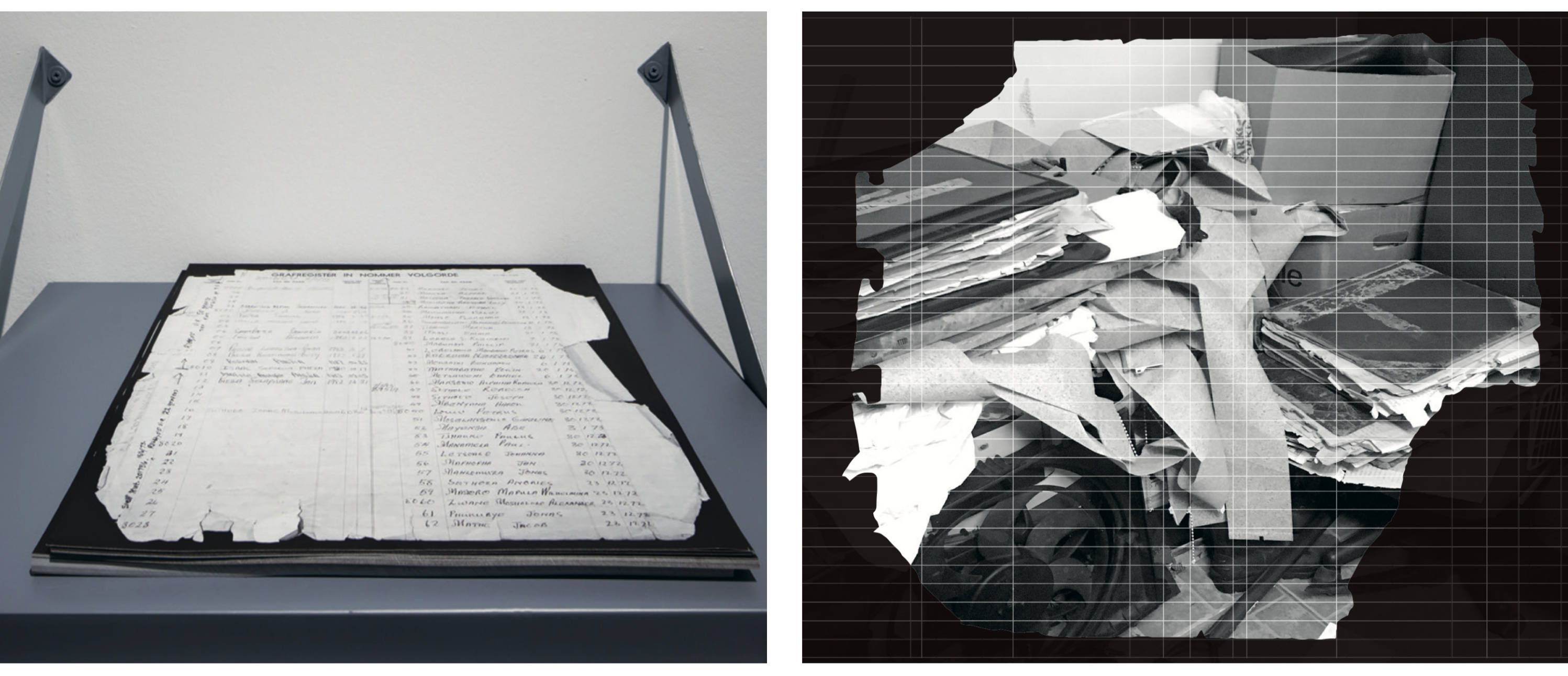

In the still-functioning cemetery offices, pages of old ledgers listing grave numbers, and names and dates of burials are strewn across the floor and piled in boxes; the paper disintegrating and torn. Lubinsky traces the contours of these decomposing pages and carves them out of marble, a stone commonly used for headstones. She has deftly inverted the fragility of the deteriorating paper and the permanence and commemorative association of marble, leaving the viewer to deeply contemplate its meaning. “Paper becomes a metaphor for the ephemerality of the bones, both of which disintegrate overtime,” she says.

Chelsea Selvan: What drew you to installation and sculpture?

TL: The reason I’ve gone with sculpture and installation is that I’ve become increasingly interested in materiality as a conveyor of meaning. The materials themselves have a story to tell. I find this a really generative way of approaching historical/archival material.

CS: Why marble as a medium?

TL: The idea to use marble came from encountering broken tombstones in a cemetery in Berlin. Some of the tombstones were made of white marble, which I was really drawn to. Once I had decided to work with marble, I found out about the geologic makeup of the stone, that it is actually made out of compacted fish bones and shells. That added another layer of meaning. Then there is also the art-historical reference to marble as a rarefied material for sculpture. This illustrates my previous point about the materials bringing their own stories with them.

CS: What’s next for you? What are you currently working on?

TL: I’m working on a new project responding to the Memorial to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp, located next to a granite quarry, where prisoners were forced work during the Nazi period. I am working with Flossenbürg granite to critically engage the Memorial complex. In this context, granite is used for gravestones and monuments, but it is also present as a naturally occurring part of the landscape, and a commodity that continues to be extracted at great human and environmental cost. What is now exposed as hardened stone was once flowing as lava 30km underground, where it was pushed toward the surface by continental shifts. Over millions of years, layers of earth eroded, causing the lava to cool and crystallise.

Through material experiments with heating the stones to the point at which they become fluid, the lifecycle of the stone is exposed. The solid material of stone, commonly put to work in service of mourning and memorialisation, is inverted into a fluid substance, one that can be imaginatively imbued with the latent potentiality of lava in the depths of the earth.

Written by Chelsea Selvan & Talya Lubinsky

View Chelsea Selvan's full exhibition, What shapes us? Makes us? Guides us? here.

View more about Talya Lubinsky here.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory