Honesty and optimism

Post-lockdown, post-hype strategies in African art sectors: How the turbulence of the post-lockdown art market is also proving to be a dynamic and optimistic time for art in Africa and, most excitingly, primarily thanks to local initiatives.

- By Valerie Kabov

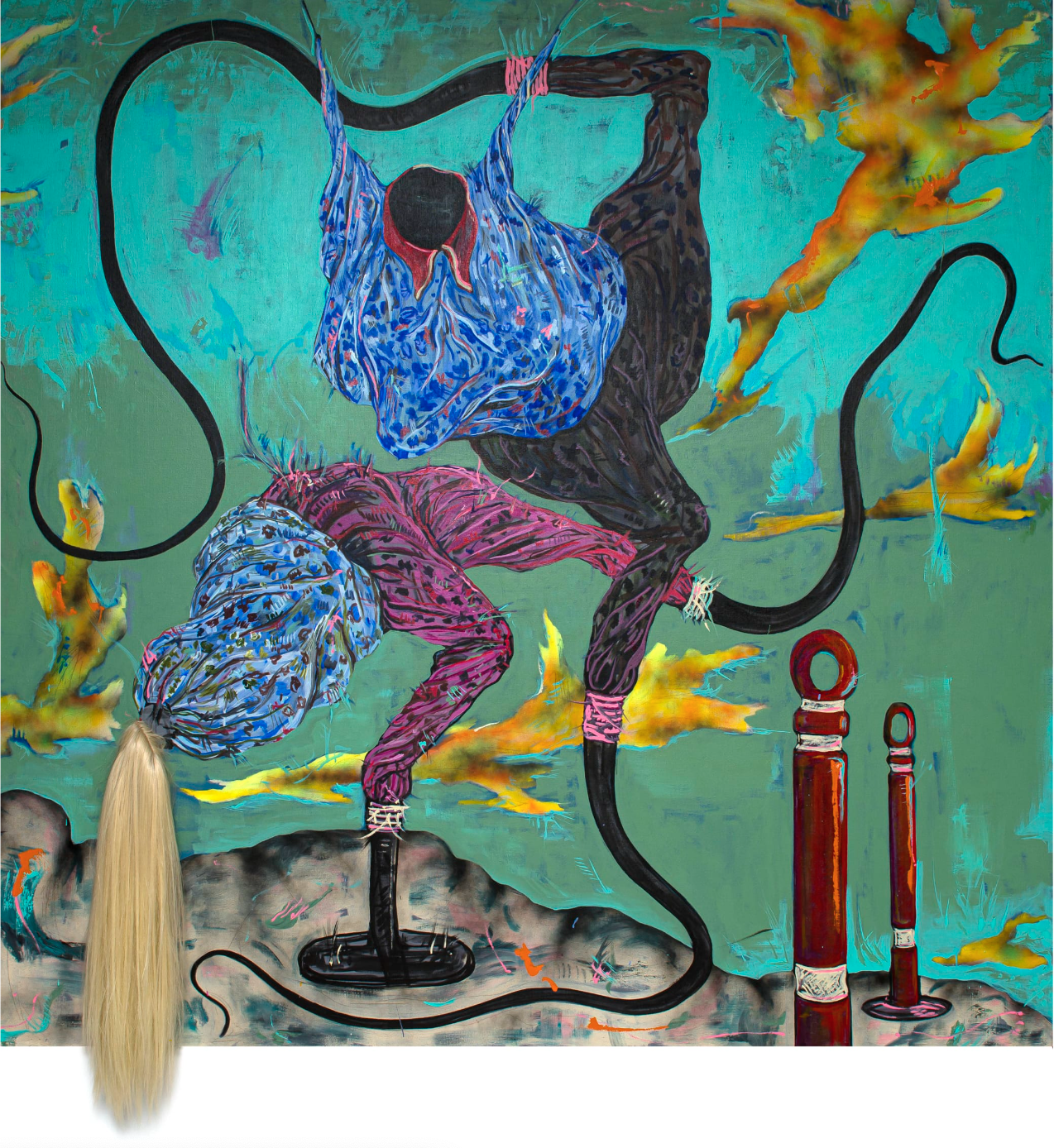

Simphiwe Ndzube, Night Birds in Tango, 2018, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, Courtesy Strauss & Co

------------------------

Covid lockdowns have precipitated numerous paradigm shifts in the art world, some of which are still in the process of emerging, especially when it comes to collector and market behaviour. Return to travel, live exhibitions and art fairs are being hailed enthusiastically, but for better or worse things are not what they used to be. In the post-lockdown re-alignment of the art world, together with global inflation and fuel cost crises, issues or access and cost of access are becoming even more urgent, especially so for the African art sector.

Two anecdotes help illustrate the situation. First was a recent catch up about art fairs in 2023 and going forward with a gallerist recently, who shared that if they are taking an artist to an art fair with a solo booth they are now planning to ask the artist to share the cost of the booth with the gallery otherwise the financial burden is becoming entirely unmanageable. Second, at drinks after an art fair, we were discussing online art platforms with a collector, who was shocked to discover that galleries pay fees between $400 to $3000 per month as membership. He was completely certain that all the benefits of the platform which were free to him were also free to galleries, rather than a case of galleries subsidising collectors and enabling the platform.

Investec Cape Town Art Fair, 2022

While price transparency has been hailed as a panacea for multiple ills of the art world over the past few years, from overcoming accusations of money-laundering to greater globalised access and democratisation of the art world, it is cost opacity that is impacting the industry sustainability.

"However, the turbulence of current art market permutations post lockdown is also proving to be a dynamic and optimistic time for art in Africa and, most excitingly, primarily thanks to local initiatives."

Even some of the most experienced collectors are absolutely unaware of the enormous costs carried by art galleries to bring art to art fairs for their benefit. Most are genuinely shocked that galleries pay on average upwards of $20,000 to rent a 20sqm space for 4 or 5 days. It seems obvious that the money has to come from somewhere but it is easy to forget when the bubbles, canapes and five-star VIP programming is entirely free to the VIPs. While luxury brand sponsor logos take prominence it is in fact workaday galleries who are the key funders of the superlative experience.

The pressure on galleries to signal success (rather than virtue) in the art world is intense, with an overwhelming majority of galleries spinning their losses at art fairs with phrases like ‘lots of great contacts’. Yet, many galleries in the middle of the market are only two to three bad art fairs away from bankruptcy and where we see extremely successful galleries suddenly shut down, usually within the first 12 months of a financial downturn, which happens once every eight years or so (the last one was in 2015/2016 so yes, we are here).

While we often hear the cries of artists as financial victims of the art world, the reality is that it is the galleries that the last to earn in the distribution and payment cycle of the art market. Consider this - breaking even at an art fair for a gallery means essentially zero income compared to the artist who gets 50% of all revenue, clear, while the gallery covers booth fees, travel, accommodation, shipping, subsistence and entertainment costs at an art fair all out of its 50% of the proceeds. All of this is dramatically easier when you sell artworks valued at $100K and above, but that is not the case for 90% of artists or galleries in the industry.

The duopoly of Frieze and Art Basel positions itself as the acme of the art world, where one feels blessed to be granted the opportunity to pay the exorbitant fees for the prestige and publicity (often, but not always warranted). For many of the other art fairs around the world the investment in the galleries’ success all too frequently ends once the gallery has paid for participation. If the gallery fails to sell, the fair has already received its payment and has little concern for the walking wounded who are occasionally even dismissed with comments like ‘you did not bring your best work’ or ‘some galleries don’t sell for the first three years when they come to the fair’ – as though someone would spend $20,000 for a five-day outing and not do their best or as though anticipation of entirely sunk costs is not something a gallery should understand when making an investment.

These criticisms have been made before “lamenting the hollowing-out of the middle market. …[and] the immense pressures the mid-market players are under, as they try to retain their star artists, show at numerous fairs around the world and maintain expensive premises that fewer and fewer collectors visit.” wrote Georgina Adams in The Art Newspaper in 2015[1]

The post-pandemic climate has made the disparity even more evident. During lockdown all participants in the art world from art fairs, marketing platforms, galleries and collectors were compelled to enter a virtual selling environment, selling through personal OVRs, online platforms, social media channels as well as art fair dedicated OVRs. Over the past three years, across the industry, both audiences and stakeholders have had a chance to adapt, assess and integrate virtual practices into our practices and also how they will fit into post-lockdown practice.

Banele Khoza, Projecting Myself, 2018-19, acrylic and acrylic ink on canvas, Courtesy Strauss & Co

Speaking to numerous gallerists at art fairs over the past nine months or so, it is very clear that the sense of urgency to buy work during the three to four days of an art fair is simply no longer there. Collectors see art fairs as social spaces to build relationships with galleries and other collectors, to educate themselves about artists and art scenes and to enjoy themselves, with the occasional opportunity to buy art then and there but just as easily three months or even twelve months down the line from a PDF in the comfort of their own home. While this by no means invalidates art fairs, it certainly shifts the business paradigm of art fairs for galleries. In the past, galleries could earn 40% of their annual revenue at art fairs.[2] This is not going to be the case going forward. Increasingly, the sentiment is to approach art fairs as revenue-neutral events. While this seems to fly in the face of the statistic emerging from the UBS 2022 Art Market Survey, which says that purchase by collectors at art fairs went up to 74% in 2022 from 54% in 2021[3], that report is a lagging indicator reflecting on the post-lockdown flurry of enthusiasm in late 2021 to 2022, which has now settled down and will reflect in the figures in the next reporting period. The here-and-now experience of galleries on the ground is different.

The priorities of galleries in the African sector require special reflection in this context. The cost of access to the global market on the continent is still dramatically higher compared to any of our peers internationally, while the general price of our artworks is on average a lot lower. This cost includes everything from cost of travel (which for anyone with an African passport includes the cost and trauma of the visa application process for anywhere in the world), cost of shipping, cost of networking and even cost of participation at an art fair (which for many European galleries is subsidised by their governments), as well as the cost of engaging institutions for artist career building, which are still overwhelmingly centred in the Global North and have no real intention to accommodate needs of a sector that despite the hype of recent years is still economically insignificant.

To underscore the point of how little the needs of galleries in art sectors on the periphery register on the global scale, the UBS Art Market report notoriously prioritises the experiences of the market at the top end both in terms of collector experience HNWs (High Net Worth Individuals)[4] and artworks above a certain price point (usually above $100,000). Africa does not feature as independent categories of the survey. In fact, when asked during the launch of the report about prospects of the art market in Africa, the author, economist Clare McAndrew struggled to find anything tangible to say[5].

Post lockdown and in the current climate of inflation and increased costs, participation in art fairs has the risk of becoming a Russian roulette, which can cost a gallery and its artists representation and existence. While this is not necessarily a drama for representation or participation in other art sectors, in the African context it definitely is. One is stuck between a rock and a hard place, not participating is not an option if one wants to grow and engage, while participating can cost you your whole operation.

Morenike Adeagbo lamented in The Art Newspaper that ‘..despite the vast majority of artists exhibited at both fairs [1:54 and AKAA] being of Black African descent, this demographic was not reflected in the gallerists representing these artists, nor in the key staff working at the fairs, most of whom were white, ” making it evident “how vital it is for the Black African art community to have a homegrown platform committed to celebrating its own history.”[6] I would argue that more than platform, the art sector on the continent must continue and insist in building for us by us models and vehicles for supporting the enormous depth of talent on the continent and securing an Afro-centric vision of African art.

While the art sectors on the continent are some of the most exciting and rich in talent, we are definitively under-resourced and under-capacitated across the entire value chain in art, including education, availability of art materials, government support, gallery systems, effective social security and health infrastructure, established art markets, taxation systems which facilitate and advantage art philanthropy and acquisition, and availability of proactive well-resourced art collecting institutions.

FNB Art Joburg, 2022

FNB Art Joburg, 2022

Over the past two decades through the emergence of contemporary art from the continent on the global stage, local galleries have been vulnerable to the risks and realities of the thank-you-very-much-we’ll-take it from here attitude by gallerists outside the continent who sign local artists and then leverage their ‘Africanness’ in ways we don’t have the capital to do. We have also been risking allowing the international market, and non-African institutions[7], to tell the ‘definitive’ story of art in Africa, simply because they had the budget to do so.

However, the turbulence of current art market permutations post lockdown is also proving to be a dynamic and optimistic time for art in Africa and, most excitingly, primarily thanks to local initiatives. Local professionals and entrepreneurs, especially of the younger generation are starting to become aware and involved in art. Moreover, the switch to remote work has motivated many Africans in the diaspora to consider and implement repatriation, boosting the numbers of educated art enthusiasts motivated to support local art scenes.

Art fairs on the continent have been crucial to mobilising this youthful energy. Speaking to the interests of younger audiences has been a strategy for Art X Lagos, which has become known as an event bringing together music and parties with art at the centre. Recognising the demographic shift has also proven successful for FNB Art Joburg, which pivoted to prioritise black, younger successful Johannesburg collectors in its programming for the return to IRL in September 2022. Equally mindful of the need to be proactively engaged in the future of the collecting audience in Africa, Investec Cape Town Art Fair in 2022 piloted a VIP trip to Harare as an exchange and activation project to support emerging local collectors and to introduce international collectors to the vibrant Harare art scene. In February 2023, Strauss & Co produced an alternative curator-led auction focused on contemporary art and to begin the shift of centres of the secondary art market for African art, away from London and back to the continent,[8] recognising the need for alternative hybrid solutions in which art fairs in partnership with galleries is both imperative but also more economically sustainable. RMB Latitude’s International Galleries Platform is one such pilot project designed to respond to the costs-and-resources challenges faced by African galleries when coming to art fairs. Putting its money where its mouth is, the fair is providing international galleries with exhibition space and logistic and even sale support, working on a commission basis.

While it was the international attention which sustained the emergence of contemporary art sectors on the continent, the future and future success of our artists and galleries belongs on the continent. The partnerships emerging between market stakeholders and audiences in Africa are showing the way forward.

Valerie Kabov

©2023

Disclaimer: The author has been involved in the following projects referred to in the article: through First Floor Gallery Harare as partner with Investec Cape Town Art Fair VIP trip to Harare, as one of curators for Strauss & Co Curatorial voices auction and as Project Advisory Committee member for Latitudes 2023 International Galleries Platform.

[1] https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/02/26/death-of-a-wannabe-mega-gallerywas-the-closure-of-blain-southern-an-outlier-or-the-canary-in-the-mine Georgina Adams, Art Market Eye, 26 February 2022, The Art Newspaper

[2] TEFAF 2015 Art Market Report

[3] The Art Basel and UBS Survey of Global Collecting 2022, https://www.ubs.com/global/en/our-firm/art/collecting/art-market-survey.html

[4] The UBS Art Market Survey surveys “over 2,700 high net worth collectors in 11 key global markets”

[5] https://www.facebook.com/artbasel/videos/789170692183812, The Art Basel and UBS Survey of Global Collecting: A Conversation, 9 November 2022 at 59’

[6] Why are so many African art fairs dominated by non-African dealers?, The Art Newspaper, Morenike Adeagbo, 28 November 2022

[7] For example, in 2022 Tate Modern published ‘African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century’, by Osei Bonsu, in the absence of comparable African publications, a book by a UK institution will become the default resource on African contemporary art history.

[8] Curatorial Voices: Modern and Contemporary Art From Africa, 28 February, 2022, https://www.straussart.co.za/curatorial-voices-modern-and-contemporary-art-from-africa/

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory