Post African Futures

Remembering one of the most important exhibitions of South Africa’s upset 2010s

- By Sean O’Toole

Muchiri Njenga, Kichwateli 2, 2015, Mixed media installation 2, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Muchiri Njenga, Kichwateli 2, 2015, Mixed media installation 2, courtesy Goodman Gallery

---------

In the whirlwind time of the Internet, years pass like decades and 2015 was, like, very long ago. Remember 2015? Vaporwave (so much irony, so much pink and purple) was at its nadir. X was still Twitter. Instagram was a mosaic of static impressions. Hito Steyerl had just debuted her immersive video installation Factory of the Sun (2015), a montage of pre-TikTok online dance videos, drone surveillance footage, cheesy gamer graphics and fictitious news, at the Venice Biennale. Bogosi Sekhukhuni was being hailed for his chatbot avatars. And Mxit, well, it died.

Amidst all this – let’s summarise it as the unstoppable march of computer mediation of life – Tegan Bristow, a Johannesburg-born artist turned scholar and co-founder of the Fak’ugesi African Digital Innovation Festival, organised the exhibition Post African Futures at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. It may well have been one of the most important exhibitions of South Africa’s upset 2010s. Perhaps. We tend to look back at the past with an uneven mixture of astonishment and disdain. What seemed punkish and new at the time now strikes me also as, well, antique, maybe even archaeological – definitely classical.

In more formal terms, Post African Futures presented a survey of metropolitan artists from the African continent and its diaspora using digital and technology-orientated art in interesting ways. Many of the participating artists hailed from Johannesburg, Lagos and Nairobi, although not exclusively. Given the remarkable pluralism enabled by digital networks, the exhibition included collaborative works by collectives of like-minded friends. Sekhukhuni collaborated with fellow Johannesburg artists Nolan Oswald Dennis and Tabita Rezaire on an interface work under the guise of their “tech-health” artist group NTU. Pamela Sunstrum and Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, friends from Johannesburg, presented Notes from the Ancients (The Disrupter X project), a collab work that was equal parts living installation and leftover prop display.

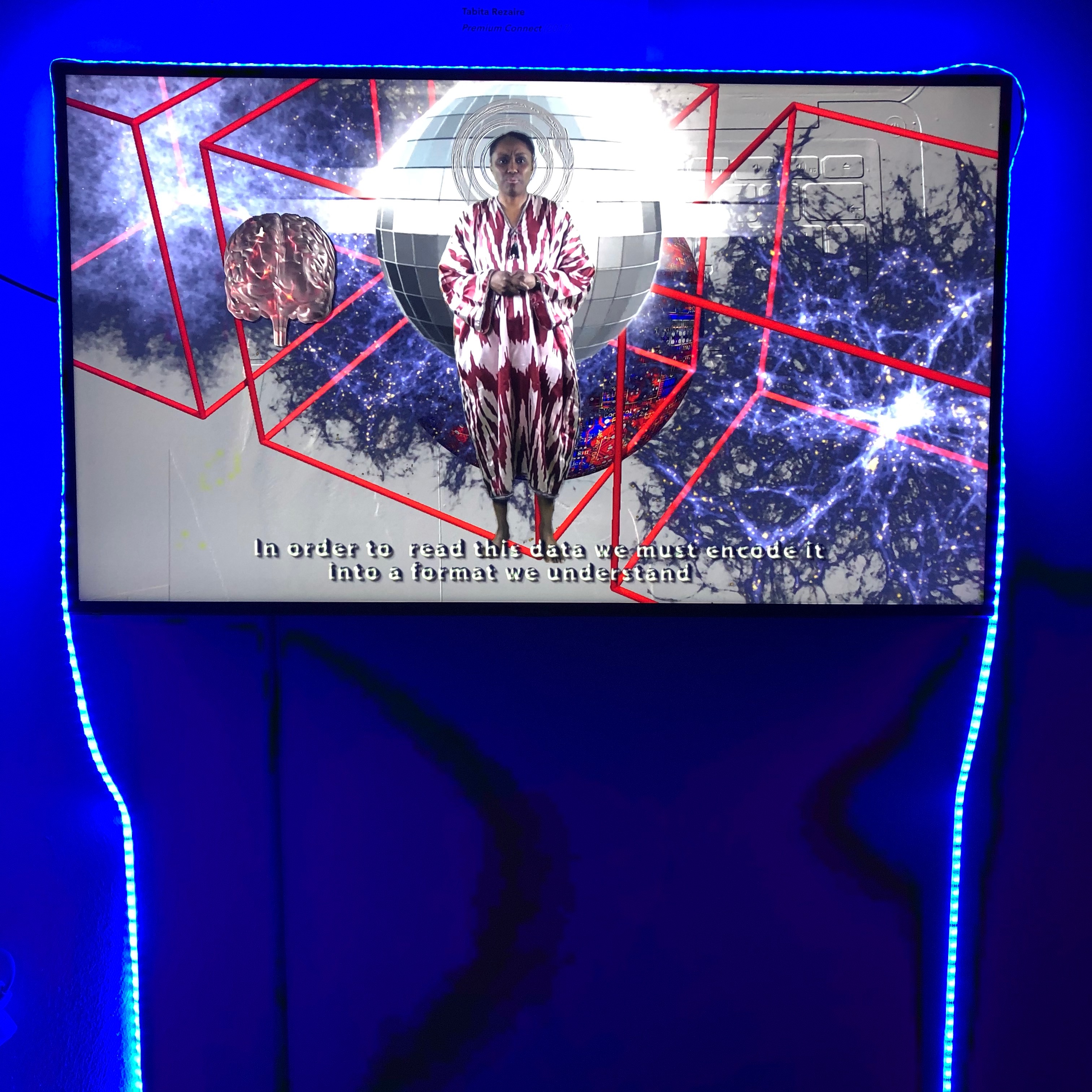

Tabita Rezaire, Still from Deep Down Tidal, 2017, Hd video, 19min Commissioned by Toke Lykkeberg for Citizen X – Human, Nature, And Robot Rights, Oregaard Museum, Den-2, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Tabita Rezaire, Still from Deep Down Tidal, 2017, Hd video, 19min Commissioned by Toke Lykkeberg for Citizen X – Human, Nature, And Robot Rights, Oregaard Museum, Den-2, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Being a show about what might concisely be termed sci-tech transformations in the making and meaning of art, Post African Futures featured a lot of works in need of electrical cables. Eskom, the state power utility, wasn’t spluttering, which helped ensure that the films and projections by Dineo Seshee Bopape, Sam Hopkins, Emeka Ogboh and Brooklyn J Pakathi, among others, enjoyed an uninterrupted run. Bristow, then a doctoral candidate in Plymouth University in England and teacher in interactive digital media at the Wits School of Arts in Johannesburg, also selected sculptural pieces by Kapwani Kiwanga, Jean Katambayi Mukendi and Muchiri Njenga. These static objects had a decidedly old-school vibe about them in a show burdened by the term Afro-futurism.

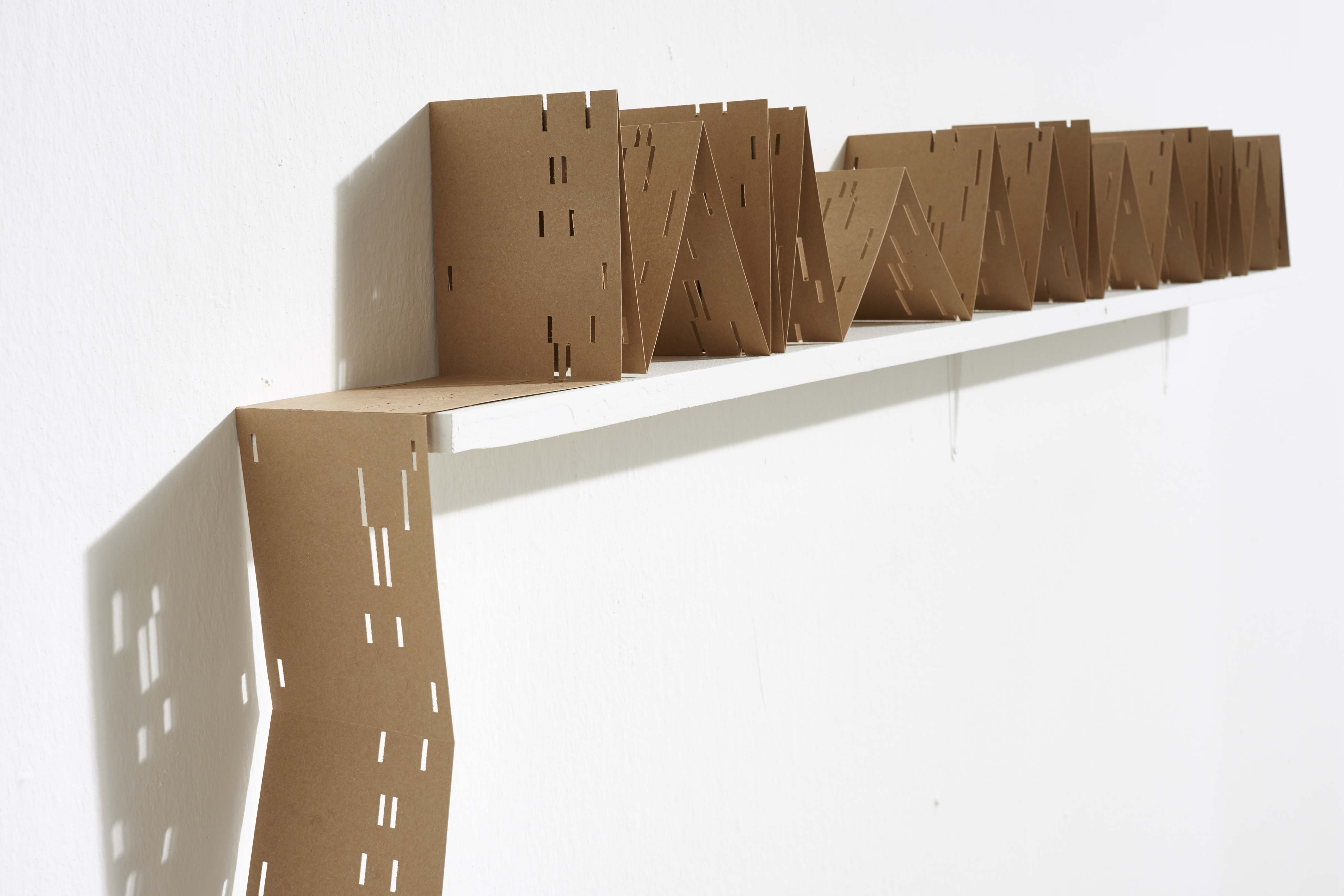

Lubumbashi-based Mukendi, an electrical engineer by training, showed one of his enigmatic paper-based machines, Migration (2015). Its making drew on skills acquired in his childhood. The artist’s mother worked as a typist and regularly brought home sheets of paper. Mukendi integrated this haptic skill with the teachings of his father about “the DNA of electricity”. “Human energy suffices when it comes to making art,” he said in a 2022 interview. Canadian-born Paris-based Kiwanga, who has family links to Tanzania and will represent Canada at the 2024 Venice Biennale, showed a perforated barrel organ card featuring the transcription of a remote divination ritual by an Ifa priest from Benin. The unfolded card brought to mind Charles Babbage’s proto computers of the 1830s, which could read cards. “My logic is more circular or spiral than binary,” Kiwanga told me shortly after the exhibition. “There’s this question of weaving between times.”

Tabita Rezaire, Positive Connect, 2017, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Tabita Rezaire, Positive Connect, 2017, courtesy Goodman Gallery

The times around 2015 were definitely agitated. Trending hashtags included #RhodesMustFall and #BlackLivesMatter. Filmmaker Laura Poitras, winner of an Academy Award for her documentary Citizenfour about the computer intelligence consultant and whistle-blower Edward Snowden, sued the US government following consistent harassment at U.S. and foreign airports. Also in 2015, scholar Shoshana Zuboff coined the term “surveillance capitalism” in a journal article exploring the “emergent logic of accumulation in the networked sphere”. Her article was largely about Google. She would consolidate her research into a widely reviewed 2019 book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. In framing her arguments Zuboff drew on a range of dead social theorists who, in her words, had “struggled to name the unprecedented in their time”.

Kapwani Kiwanga, Ifa Organ, 2013, organ paper, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Kapwani Kiwanga, Ifa Organ, 2013, organ paper, courtesy Goodman Gallery

This is precisely what Bristow set out to do in her exhibition, albeit substituting theorists for live-wire artists interested in “exploring and being critical about Africa’s cultural relationship to new and communications technologies globally,” as she put it to Kabelo Mnisi. Her choice of artists was prescient, even in 2015. Take Rezaire and Sekhukhuni. Both artists were pushing back against what Rezaire at the time described as the “occidental hegemony” of the Internet. “The Internet is such a violent and oppressive space and we have to cope with it,” said Rezaire, who moved to Johannesburg from London in 2014 with a background in economics and filmmaking. “There is much about Internet online protocols and consumer culture that reflects our IRL white reptilian capitalist systems,” said Sekhukhuni in 2017, shortly after winning the third edition of New York-based digital arts organization Rhizome’s Prix Net Art Award.

During the run of Bristow’s exhibition Facebook, now Meta, announced that it would open its first African office in Johannesburg. “Africa matters,” said Nicola Mendelsohn, Facebook’s vice president for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. How and why technology matters to Africans is, however, very different to those presumed by transnational corporations, who are often compelled by westernised assumptions that technology is “a disembodied entity, emptied of social relations,” as anthropologist Bryan Pfaffenberger put it 35 years ago. Far from being a value-free tool or product, wrote Pfaffenberger in an insightful 1988 essay, technology is “a total social phenomenon”.

Muchiri Njenga, Kichwateli 2, 2015, Mixed media installation 3, courtesy Goodman Gallery

This total phenomenon, which was largely ignored by scholarship around technology in Africa, prompted Bristow to initiate her research project disguised as a public exhibition. In 2017 Bristow completed her doctorate. It is framed by a chewy title but its contents include digestible prose illuminating her motives for making an exhibition. Take this passage about her engagements with South African and Kenyan youth, a generation Bristow characterises as at the forefront of how technological, aesthetic and cultural engagements are being formed in relationship to older African traditions.

Tabita Rezaire (centre) at Amakaba, French Guiana, courtesy of the artist

Tabita Rezaire (centre) at Amakaba, French Guiana, courtesy of the artist

“This group are essentially engaging in an ‘act of composition’ that is changing the way African societies define themselves in the state of technological globalisation,” writes Bristow. “Scholarship on Africa fails to contain their context or their intentions, viewing instead the relationship to African traditionalism through the lens of colonial anthropology, or the relationship to technology through the lens of First World development studies.”

As I wrote at the outset, 2015 was like nearly a century ago in Internet time. Now is a different epoch. NFTs salted already poisoned digital earth. If 2015 was all about post-Internet art, now is about post-blockchain and A.I. art. It is a different epoch. This is true of the lives of the tight circle of artists who appeared in Post African Futures.

Sekhukhuni now lives in Portland, where he cofounded INFANT, a design company interested in “architecture and cognition, planetary affordances, and the onto-epistemological status of science and mathematics”. Bopape and Dennis, while still based in Johannesburg, have an essentially nomadic practice linked to Europe. Ogboh is making astounding sound work from his base in Berlin. And Rezaire has tapped out of the Internet and South Africa. “I am not up to date,” Rezaire told me in a recent Zoom interview from a cacao farm and yoga retreat in her ancestral homeland of French Guiana. “I know nothing about A.I. and can’t talk about it.”

As for Bristow, she is now director of education for Diriyah Art Futures, a work-in-progress digital arts centre being piloted by the Ministry of Culture in Saudi Arabia. I reached out to Bristow. With the luxury of time and distance, I asked her, what does she think Post African Futures got right, and wrong?

Tegan Bristow, Fakugesi, 2019

Tegan Bristow, Fakugesi, 2019

On the upside, she says, the exhibition critically recognised the existence of new media and digital arts in Africa, art born from African locations. “I felt like many African contemporary artists challenging this intersection of critical creative practice and technology were being shoved under an ‘Afro-futurist’ umbrella,” says Bristow, referring to the term coined by American literary critic Mark Derry in 1993 and definitively cremated two decades later by artist Martine Syms in The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto. It was “far too generalised” in its application, adds Bristow, and largely wielded as a tool of Euro-American contemporary art gallery set.

As to getting things wrong, Bristow says her exhibition was the “first draft” of an idea. “It needed more work and I should have followed with more shows or toured the show internationally. I did not persevere enough to support the position for new media and digital arts.” Fak’ugesi seemed a better place to direct her energies around access to technology and creativity.

The festival was anyways a version of Post African Futures, “but operating on the grimy streets rather than in galleries and trying to find ways to support critical practice in more pop culture locations and also support younger artists entering the space,” says Bristow. Artist Natalie Paneng, who earlier this year held her debut solo with Eigen + Art in Leipzig, was a social media intern with Fak'ugesi before she staged a show as a resident artist of the festival. Call it a virtuous circle.

Bogosi Sekhukhuni Consciousness Engine 2- absentblackfatherbot, Dual Channel Video Installation, 2014, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Bogosi Sekhukhuni Consciousness Engine 2- absentblackfatherbot, Dual Channel Video Installation, 2014, courtesy Goodman Gallery

“I think there is generally much more openness to digital arts,” adds Bristow. “It is mainstreaming pretty hard and I also feel the impact on culture and society is far more visible and therefore there is also interest for critical artistic and cultural engagement.” Buying and collecting digital art is a different matter. “This work is still difficult and unstable in older art collecting models and South / African contemporary art galleries are still trying to figure out its income-generation opportunities. But outside of this there is great work being done in photography, film, VR film and games that shows a significant exploration of A.I. models and new technologies.” But, cautions Bristow, this is occurring in larger, wealthier international contemporary art spaces, film, VR or game communities. “I think the South / African gallery scene is still trying to figure out how to engage and monetise.”

Emeka Ogboh Follow Àlà, 2014 2-channel video, stereo sound, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Emeka Ogboh Follow Àlà, 2014 2-channel video, stereo sound, courtesy Goodman Gallery

One form of engagement, a precursor to buying, is due diligence. Or, as Bertolt Brecht put it in a poem, “Study the ABC; it is not enough, but study it!” By which I simply mean, pause and reflect on the long history of digital art and artists in South Africa. Post African Futures, an exhibition located somewhere between the murky beginnings of computer-influenced art and the everything-digital now, is a good place to start.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory