LAWRENCE CALVER – INFINITELY GENTLE

------------------

- by Ashraf Jamal

The Swiss-English artist, Lawrence Calver, is in love with Rothko, though he is no painter. Sewing, dyeing, bleaching, are the integral elements in the creation of his art. The sewing machine was at the ready on his arrival at his studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, the location of which could not be more fitting – the city’s now defunct clothing and textile hub. Destroyed by the sweatshops in the East, this semi-industrial hub sputters on, its central artery, Victoria Road, lined with stores selling bolts and off-cuts. In its depleted state, the textile industry speaks reams about port cities as the critical global interface in the maritime era. What we now think of as a peculiarly West African textile, for example, is anything but.

Lawrence Calver, portrait, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Calver and I are discussing ‘mud cloth’, a cotton fabric whose cultural significance is deemed African, its putative place of origin, Mali. However, maritime historians tell a very different story in which Coromandel, in India, is recognised as the key point of export of cloth. Arriving in Kilwa, on the East coast of Africa, where, vividly, and unforgettably, bolts were exchanged for elephant tusks (deployed as picket fences!), the cloth then journeyed upward and westward. This transaction and migration, along with Dutch control of the industry in Europe, before a British takeover, tells us some revealing truths – that points of origin are always misnomers, that the history of material culture is complex, nations and continents implicated in a rich tapestry – in this case the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and Europe. That Calver’s great-grandfather was a Swiss trader in cloth and skins between Asia and Europe, further underscores this intimate genealogy.

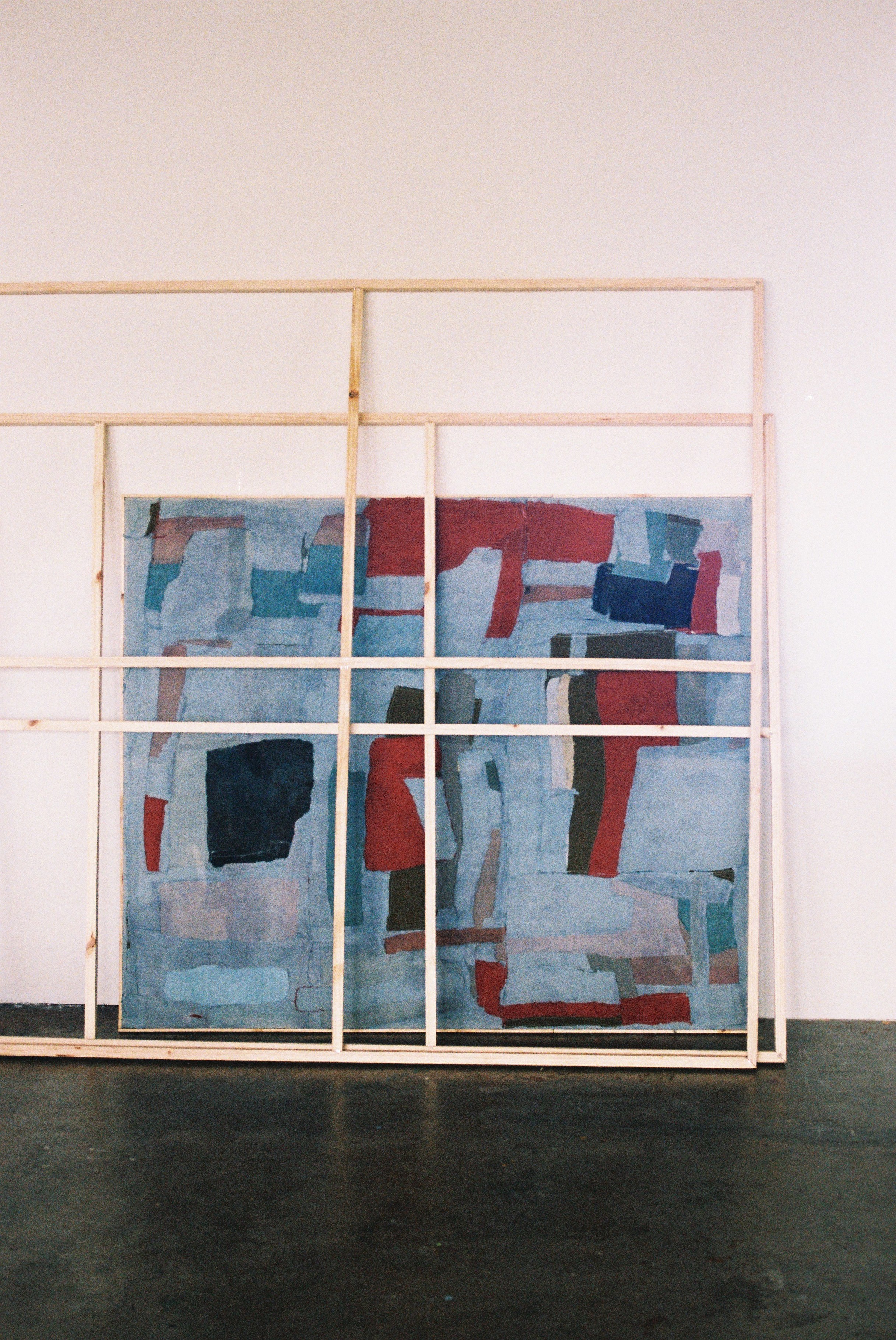

Lawrence Calver in studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Lawrence Calver in studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Calver is an abstract artist, his focus is textility – the text as tissue, as ‘a ready-made veil’, but also as a ‘generative idea that the text is made, is worked out in a perpetual interweaving’. Here, Roland Barthes is intrigued by a language game – text-textile-techne, and the Latin root, texere, to weave. This overlay – everything is thus, intertextual – is especially compelling for Calver, whose construction and generation of meaning, as text, is integrally connected to the stitching and allocation of off-cuts. That he works on both sides of a thinly transparent canvas – attentive always to light, the greatest influencer in design – and colour blocking – the vital language of his work – is telling. A variant of reverse glass painting? Not quite. For what primarily inspires Calver is the mood of a ‘collaged’ work.

Lawrence Calver, Untitled, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

I’m not sure if collage is a fitting descriptor. After all, for Max Ernst, collage supposes the combination of dissonant materials on a plane that is further disjunctive. Calver, however, produces large canvases in which unevenly cut textiles are sewn together into an irresistibly beautiful and gentle concert. Aurally, I’m reminded of the music of Eric Satie, of sounds as limpid, as soft, as easeful, for this, undoubtedly, is the mood and sonography of Calver’s art. There is, for instance, a patchwork, rather than collage, composed in a symphony of pink, with elements of blue and orange subtly integrated. In the composition, pieces are cut and shifted about. If the colour field is deemed too strong, too stringent, the composition is then bleached, or, inversely, redyed. Colour is never a given in Calver’s world. And if Rothko is a core inspiration, it is because he understood the integral and numinous matter of light.

Lawrence Calver, in his studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Lawrence Calver, in his studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Calver declares that he ‘brings out what is already there’. This supposes an artist who treads exceptionally lightly, who refuses the imposition, say, of ego, for whom composition is an intuitive, even Taoistic, exercise, that allows as much for release as it does composition. Here, again, Satie returns to me as an infinitely gentle – though not infinitely suffering – thing, for his world, like Calver’s, and unlike T.S. Eliot’s to which I’m inferring, holds little interest in pain, whether psychic or physical. Rather, Calver is wholly immersed in the sonority and beauty of the world. Indeed, a work is completed only when he sees ‘the beauty in it’.

Lawrence Calver, in his studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

That Calver doesn’t like his ‘hand being in the work’ further illuminates the nature of its making, in which removal is not detachment. The hand, typically, is integral in the making of craft and art. Calver’s hand, or hands, and presumably a foot attached to a sewing peddle, assume a constructive interposition when stitching the work. But when it comes to dyeing and bleaching? Surely here hands get ‘dirty’ as it were? That Calver insists upon the withdrawal of the hand in art, must refer to something other, given that its presence is irrefutable. I think that Calver’s conceit hangs on desire – what he wishes the viewer to experience and see, which is not the mechanics of their making but the sonority of their unique being. His is a vision of art that is transcendental and sacramental.

Lawrence Calver, in his studio at the Cape Town Art Residency, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

This ideal in no way overrides the fact that the making of his art requires not only a sewing machine but ‘a mental drive and physical process’. Calver’s core point, however, concerns the economy of reception of his work – how it is seen, what it is seen to be, how it is felt, or intuited – which favours the sacral, typically associated with Rothko’s paintings. This predilection on the part of the artist is not a personal quirk, but historical. That abstraction now dominates the global optic in the artworld is, in fact, unsurprising. After all, after a recent and still current history consumed by moral piety and sententiousness, by rage and divisiveness, the artworld finds itself exhausted. Now, identity politics holds comparatively little sway. Now, we no longer care to be told what to think, or when to shut our mouths. Now, we find ourselves returning to consolatory art. As Matisse famously remarked, on returning home after a tiring day at work, the businessman wishes for nothing more than to kick off his heels, slump into a cosy armchair, and behold a restful work of art.

Lawrence Calver, Untitled, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

Lawrence Calver, Untitled, photo credit: Yulia Zhilina

This is Lawrence Calver’s goal. He well knows that abstraction is not an intellectual game, but the stuff created by theosophists and mystics. It is that tradition, inspired by wonder, drawn to beatific contiguities, which he has made his own. One particularly splendid work has stayed with me. Calver has worked on both sides of the thin canvas, drained the colour, so that what we see, barring one irregularly shaped block of ox blood red, is a subtle compound of striped and matte creams, with one blob of creamy yellow. Nougat comes to mind, something milky. But this, contra Barthes, is not milk that turns, but a milk, some balm of pale custard with slivers of berry, which is utterly soothing. Because now, we are done with moral peacocks, done with noise. Now, we linger longer, inhabit the world more slowly, gently … kindly.

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory