How will curators institutionalise and interpret the portraiture trend?

It’s time for museums to harness a dialogue on the importance of this genre, one that is removed from speculation in the art market.

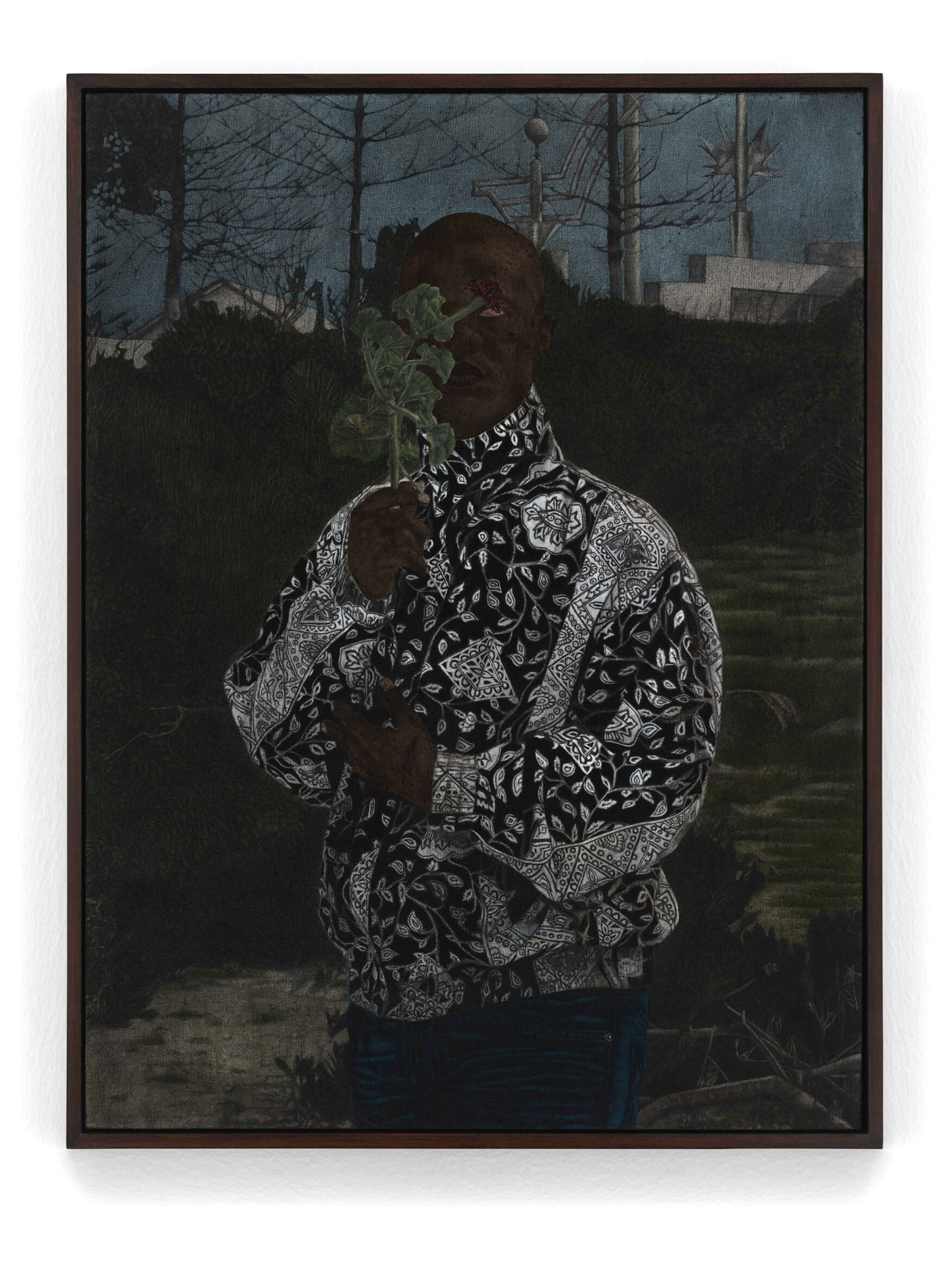

Cinga Samson, Okwe Nkunzana 4 (2021), oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm, image courtesy: the artist

There is such an abundance of portraiture at art fairs, gallery shows, online art platforms and auctions dedicated to African art that collectors are spoilt for choice. This has caused some confusion. Is this a short-lived trend, are the prices too high, and who or what kind of artworks are important? Not surprisingly, collectors are looking to museums and curators to make sense of this proliferation of portraits, but this presents another set of questions. Can it be done given it is a market-driven turn? Would institutions simply fuel more economic speculation around known artists? Are curators interested in engaging with some works that may be all style and no substance?

Undoubtedly, institutions and curators do need to weigh in on portraiture. And perhaps it should involve more than simply dragging out portraits produced by other Black artists from previous generations. Most certainly, the slew of portraits young African artists are producing boast stylistic characteristics in common that suggest this is part of a ‘movement’. The sitters' features tend to be highly stylised. The palettes are typically vibrant and textile patterns and other decorative sartorial details are vital to the visual character of these works. Another prominent feature has been the novel or different painterly treatments of the skin of the sitters, drawing attention to their Black identity. Typically, the subjects are young and attractive. In this way, these portraits tend to exude, beauty, joy, abundance and optimism. This new generation of African artists is celebrating their Black identity in an unprecedented way.

Yet the perception is that this is a market-driven phenomenon galvanised by white or Asian art collectors looking to profit from sharp rises in value. This may only be a feature of this trend at the high-end of the art market, though it has no doubt given younger artists the confidence to dig deeper into this genre. The relationship between art and commerce can be beneficial to advancing a movement in art.

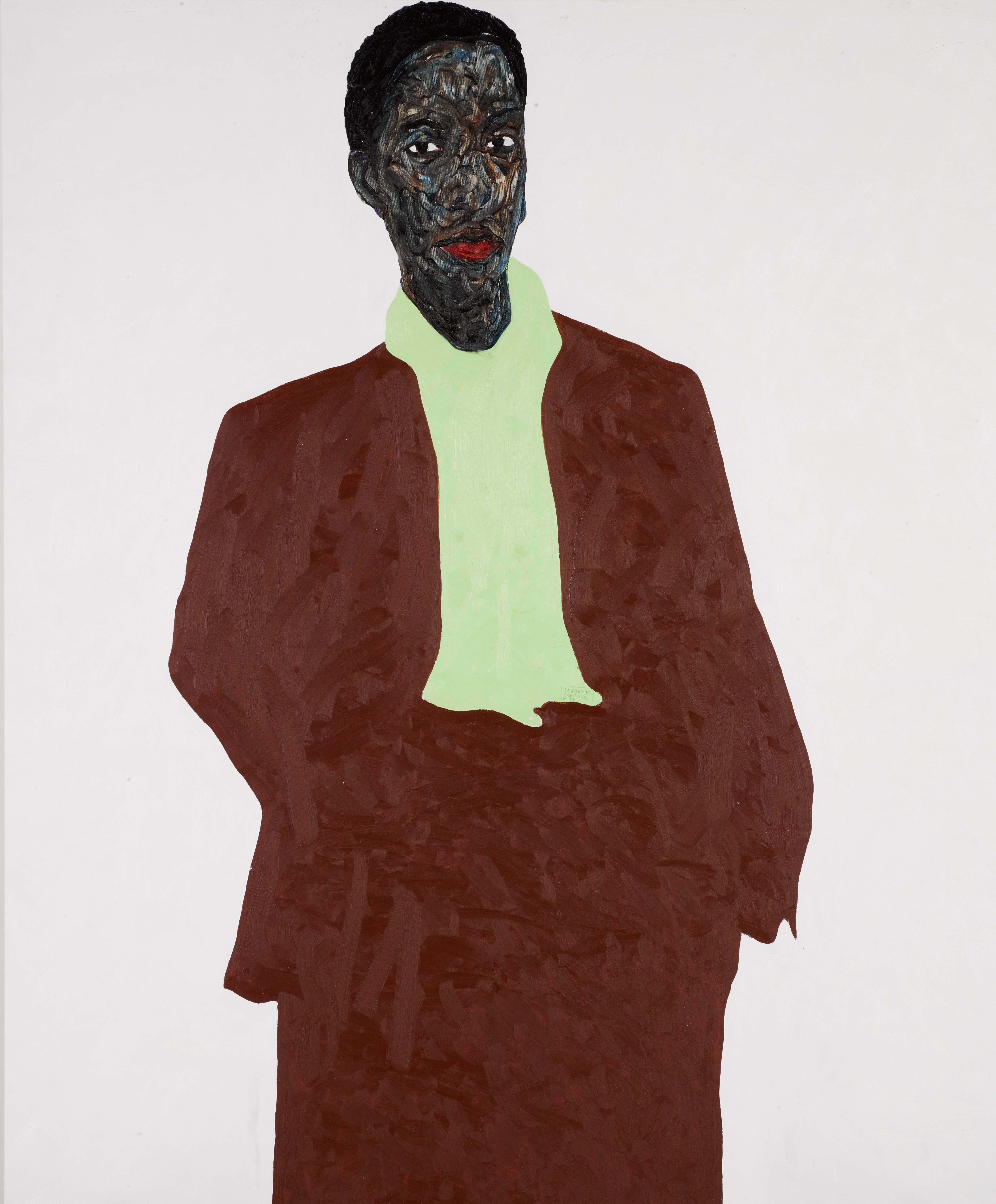

Amoako Boafo, Untitled, 2018 fetched $313 087 at a Sotheby’s London sale in 2020

Undoubtedly, speculation surrounding this genre is linked to the rise and attention of the Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, who first made collectors and the African art market sit up when the work The Lemon Bathing Suit sold for $880,971 (R14-million) at a Phillips London auction in 2020 – it was estimated at $40,000 to $65,000. Of course, it would later emerge that Boafo had teamed up with two collectors to buy the work back – but that is another long story.

This led to many Boafo works coming to auction in quick succession as buyers decided to cash in while he was deemed hot. His art wasn’t simply highly valued at auction out of the blue – it had been gradually gaining interest and attention through several American dealers and institutions, from the Roberts Projects to the Rubell Museum, where he was artist in residence in 2019. As such it was institutions in the first place that created fertile ground for his art to be prized in the market.

Different interpretations of the portraiture genre were to be found at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair in February this year. Image by Stephanie Veldman

However, you have to dial back further to when Boafo came to the attention of American art dealers – through the artist Kehinde Wiley, who allegedly found the Ghanaian artist on Instagram and promptly bought a work and alerted several dealers.

Wiley is not an incidental figure in this explosion of Black portraiture, you could argue he is the forerunner, particularly when you consider the characteristic features of his art – hyperreal renderings of Black subjects, most often situated in de-contexualised environments, separated from ‘reality’ via a heavily patterned background that can be read as wallpaper. Wiley has often borrowed poses from classical Western art paintings, thereby veritably rewriting the history of the canon to insert Black subjects.

As such this portraiture trend has been characterised by a transatlantic relationship, not only via Wiley’s influence, but also in the fact that its prominence and value in the market – as per the Boafo example – appears to have gathered steam in the US through a cluster of galleries, institutions and collectors based in that country.

Institutions are by their nature slow to react to new developments in contemporary art - they have historically been geared to preserve older works and engage with the past. Curators in the US are only now beginning to interpret, and pick through this trend, largely attempting to root it in a historical trajectory, such as with Christine Kim’s Black American Portraits, which is touring several museums in that country that include the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The show presents more than 200 works produced by African American artists from 1750 to 1950 but also encompasses numerous contemporary artists, which naturally include Wiley but also a generation of painters working in a figurative vein, such as Amy Sherald and Barkley L. Hendricks.

There is a historical precedent for works of portraiture. Works by BENEDICT CHUKWUKADIBIA ENWONWU are already well known and appreciated. The Blue Headscarf from 1953, oil on board 30.5 x 24.5cm, sold for $177 234 at a 2021 Bonhams London sale

The exhibition text promoting it suggests its importance lies in chronicling “the ways in which Black Americans have used portraiture to envision themselves in their own eyes. Countering a visual culture that often demonizes Blackness and fetishizes the spectacle of Black pain, these images center love, abundance, family, community, and exuberance (stet).”

From this point of view, the current portraiture trend is eliciting interest in historical works that have not had much institutional or public interest, allowing for many overlooked artists from the past to gain visibility, and are placing Black identity at the centre of discourse on art.

Interestingly, Kim’s exhibition did include studio photography, which links up with previous assertions that there is a strong connection, or one could be forged discursively in the context of an exhibition, with the current fixation artists have with portraiture and the studio portraits produced by the Malian, Seydou Keïta, James Barnor in Ghana from the 1950s, Salla Casset or Meissa Gaye in Senegal in the 1940s, or Malick Sidibé.

Collin Sekajugo’s portraits, featured at the Uganda Pavillion at 59th Venice-Biennale

The list of African artists primarily producing portraits is long and includes those that are currently doing well in the secondary market such as; Cinga Samson, Zemba Luzamba, Isshaq Ismail, Oluwole Omofemi and Nelson Makamo. However, there are many others working in this genre, particularly from countries such as Ghana and Nigeria which include; Qhamanande Maswana, Aplerh-Doku Borlabi, Aviwe Plaatijies, Sphephelo Mnguni, Oliver Okolo, Kelechi Nwaneri, Tafadzwa Tega, Atanda Quadri Adebayo, Kwesi Botchway, Juwon Aderemi, Afia Prempeh, Damilola Adeniyi, Lord Ohene, Adegboyega Adesina, Ikeorah Chisom Chi-FADA, Feni Chulumanco and Peter Ojingiri. Many of these artists are young – born in the '90s and are part of the ‘selfie-generation’. There is an argument to be made that this portraiture revival is very much rooted in digital culture. Think of the different APPs to filters that rely on artificial intelligence to ‘perfect’ a subject and re-colour, flatten and stylise the setting too. Or what about the idealisation of reality that defines social media? Our digitally driven visual culture has surely influenced this generation of painters.

There has been little institutional or curatorial engagement in Africa with this portraiture turn, barring a few commercial shows staged by Azu Nwagbogo in Lagos and an exhibition titled Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt curated by Anelisa Mangcu and Jana Terblanche during FNB Art Joburg’s programme in that city last year.

Koyo Kouoh, director of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art (Mocaa) in Cape Town, looks set to get stuck into portraiture, though interestingly, she has shifted the purview with the terms "representation and figuration" in an exhibition to be titled When We see us.

Preparation and research for the exhibition have begun with a series of online talks. As such she doesn’t appear to be engaging with this topic in a superficial way nor is the dialogue in the hands of one curator – the results will presumably be a show that reflects the content of the conversations between all the invited speakers for this programme. Of course, with such a wide topic and so many people in conversation, the exhibition could just end up being one big rambling show that says nothing in particular. But, perhaps this is okay for the first ‘figurative’ show of this nature.

Oluwole Omofemi, Untitled

Not unexpectedly, the transatlantic link has come up – largely with the inclusion of Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of Studio Museum in Harlem, in the US, being part of the first webinar dealing with the ‘poetics of Black figuration.’

She referred to this ‘uncoupling’ of portraiture from figuration suggesting they are linked but are different. Is this uncoupling a way of navigating around the perceived lack of substance or flighty-pop or market-driven aspect to portraiture?

Divine Fuh, a social anthropologist who is the director of the Institute for Humanities in Africa at the University of Cape Town suggested that this focus on the figurative representations of Black subjects in art is linked to a “project of humanising oneself.” This could be more relevant to portraiture.

A market-driven trend in the art world doesn’t necessarily pivot on economics or greed but is a measure of societal shifts, suggested Golden.

“It is interesting that the market is needing these images, needing artists to create them now,” she observed.

- Mary Corrigall is a Cape Town-based art commentator, advisor and independent researcher

Further Reading In Articles

African Artist Directory